By Mark Sheaves

Statues and plaques marking the lives of famous leaders of Spanish American independence are scattered across the city of London, appearing out of nowhere like ghosts of a long-forgotten past. At Belgrave Square in southwest London, “El libertador” Simón Bolívar stands in a statesman like pose offering the following oration: “I am convinced that England alone is capable of protecting the world’s precious right as she is great, glorious, and wise.” Across the city, plaques commemorate the London lives of two other early nineteenth-century Spanish Americans: “Argentine soldier and statesman” José de San Martín is celebrated at 23 Park Road in northwest London; while at 58 Grafton Way, the “Poet, Jurist, Philologist, and Venezuelan Patriot” Andres Bello left his mark. What are these Latin American memorials doing in the capital of England?

Also at 58 Grafton Way, a blue plaque celebrates the “precursor of Latin American Independence,” Francisco de Miranda (1750-1816), who lived at this address between 1802 and 1810. Now named Miranda House, this site was the central hub for the expanding community of intellectuals, poets, and patriots who migrated from across Spanish America to London in the early nineteenth century. Over dinner and drinks the exiles discussed concepts of liberty and equality alongside influential politicians and intellectuals like Jeremy Bentham. Far from home, they dreamed of an independent “America” and, in the process, London became an American City, brimming with discussion about how to best set-up the independent republics that would emerge.

At the heart of this community was Francisco Miranda, the subject of Karin Racine’s book, Francisco de Miranda, a Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution. Racine argues that while Miranda’s political ideas were often contradictory and his military campaigns were poorly conceived, he played a key role in the Spanish American independence efforts as a motivator and networker in global cities like London. Travelling extensively across the Atlantic world, and beyond, Miranda introduced disaffected Spanish Americans to North American and European sympathizers. By doing so, he provided support and connections for the exiles and gave them a sense that they could achieve their goals. Cosmopolitan elites scattered in cities across the world, then, entered a global conversation on the liberation of Spanish America because of the efforts of charming connected lobbyists like Miranda.

At the heart of this community was Francisco Miranda, the subject of Karin Racine’s book, Francisco de Miranda, a Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution. Racine argues that while Miranda’s political ideas were often contradictory and his military campaigns were poorly conceived, he played a key role in the Spanish American independence efforts as a motivator and networker in global cities like London. Travelling extensively across the Atlantic world, and beyond, Miranda introduced disaffected Spanish Americans to North American and European sympathizers. By doing so, he provided support and connections for the exiles and gave them a sense that they could achieve their goals. Cosmopolitan elites scattered in cities across the world, then, entered a global conversation on the liberation of Spanish America because of the efforts of charming connected lobbyists like Miranda.

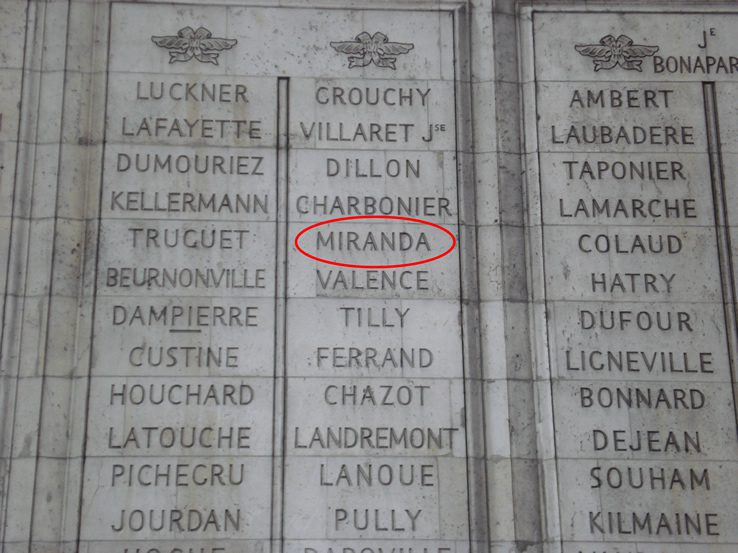

Racine traces Miranda’s journey through archives in ten countries, from Caracas, through the United States, Europe, Asia, Russia, the Caribbean, and to his death in a Spanish jail. The author reconstructs Miranda’s personal experiences participating in key events and the network of friends and acquaintances he made on his global odyssey. Along the way he picked up ideas and tied together his Atlantic community. In the US he met George Washington and discussed the political system of the newly independent US. In Kiev, he entered aristocratic society and may have had an affair with Catherine the Great. The French Philosophes caught his attention and he participated as a general during the French Revolution – his name is inscribed on the Arc de Triumph in Paris. But it was in England where he felt most at home, marrying Sarah Andrews, the daughter of a Yorkshire farmer, and having two children. From his home in London, he developed an admiration for British aristocratic constitutionalism and it was there where he could most fully enjoy the company of fellow Spanish Americans. Racine’s Miranda, then, appears as a compilation of the myriad understandings of liberty that circulated in aristocratic and elite circles around the Atlantic, and beyond, and most importantly as a connector of people within this world.

The transatlantic (or global) figure of Miranda that Racine presents inhabited a social milieu of wealthy individuals enthused by political ideas about liberty, but remote from the realities of Spanish American society. Racine’s biography successfully shows that his privileged upbringing and traditional education in Caracas placed Miranda in a world already divorced from the majority of people inhabiting what would become Venezuela. His journey around the Atlantic did not represent an education in “Western Ideas,” because he was already well versed in the current political and philosophical discourses. Miranda, like his fellow Spanish Americans in cities across the world, was an active participant in debates about liberty and equality with a cosmopolitan elite. While Racine could have made more of the impact of Spanish Americans in London on the thought of individuals like Bentham, or considered the political and economic reasons why these Spanish Americans were so warmly welcomed across the Atlantic world, this is not an intellectual or diplomatic history. And as a work of biography, Racine successfully situates Francisco de Miranda as part of transatlantic cosmopolitan elite actively engaged in political debate on his own terms, rather than as a follower of Western Europeans and North Americans.

The author also offers insights into the condition of exile, which formed the focus of her previous publications. Racine uses Miranda as a case study to reveal how the exiled figure simultaneously grew more divorced from the society where his born, but increasingly longed for an imagined idealized version of home. Miranda’s was “a mind whirling in distant isolation.” He was “an American patriot who did not understand America,” which is evident in his failed military campaign in Venezuela in 1806 and his brief participation in the First Venezuelan Republic in 1810. His final fate — rotting in a Spanish prison — best captures his failure to translate his ideas to the realities of America. Yet despite his desperate condition, he remained firm in his conviction that he would one day lead the Spanish American movement for independence. He hatched escape plans with his British bankers in Gibraltar and he wrote letters that stressed the possibility of liberty for his homeland. He may not have led Spanish American independence, but he certainly contributed his energy and community building skills to the movement. Individuals from across the world were willing to die for the ideas Miranda and his Atlantic community stood for, and the groups that fought for Spanish American independence were equally transnational in nature. Even if he did not understand Spanish America or how best to organize the independent nations there, Miranda matters.

Miranda en La Carraca, Arturo Michelena’s depiction of Miranda’s last days, imprisoned in Cádiz, Spain. Galería de Arte Nacional, Caracas, Venezuela (1896) (Via Wikimedia Commons)

Karen Racine, Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution 1750-1816 (Wilmington DE: Scholarly Resources, 2002)

You may also like:

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott