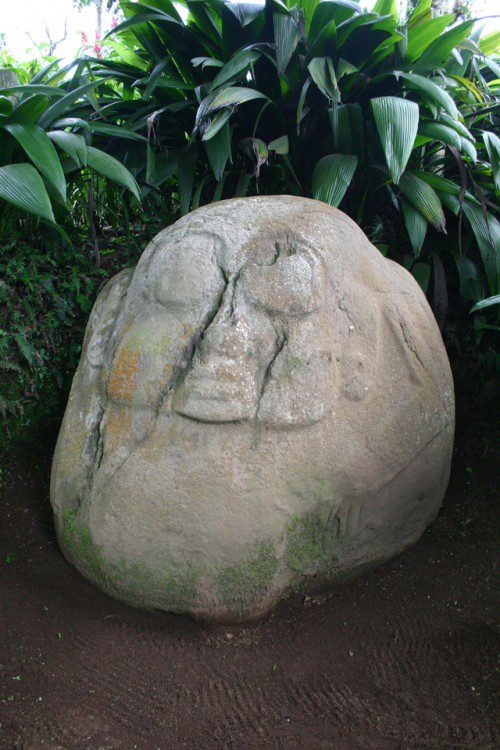

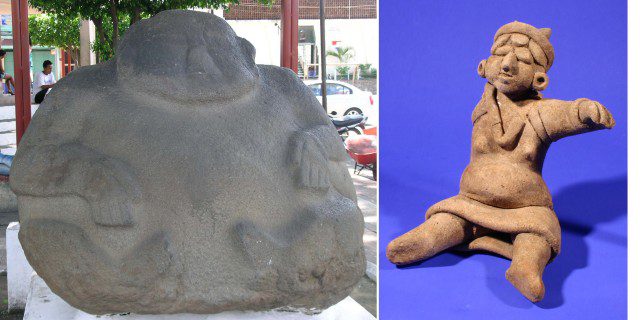

I had long been aware of the enigmatic sculptures known colloquially as “potbellies”or, in Spanish, barrigones, with their unusual features, often enormous bellies and recurring facial features. They visually dot the landscape of southeastern Mesoamerica, especially along the Pacific coast and slope of Mexico and Guatemala, as well as throughout the highlands of Guatemala. Although they are less common in other regions of Mesoamerica – in the Maya lowlands of Guatemala, for instance, or further northwest in Mexico – they nevertheless make occasional cameo appearances.

The mysterious potbellies fascinated me for several reasons. They are huge: some are hewn from massive boulders up to several tons in weight. They are unusual, with their bulging paunches, tightly closed eyes with puffy lids, and swollen cheeks. They are abundant, with over 130 known and they appear at sites of all different scale, from enormous cities that politically dominated regions to smaller subsidiary sites within their political orbit. They are also early, having made their first appearance in Mesoamerica by 300 BC.

But, unlike the elegantly carved stelae (or tall stone monuments) that date to the same period and often render complex narrative scenes concerning mythology and rulership, the potbellies are simple. Giant, often, but simply carved, the boulders from which they are rendered are still readily discernible and lend their sheer weight and enormity to the visual impact of the sculptures. Although they had always intrigued me, I had long focused on the narrative stelae and their relationship to expressions of kingship.

It was hard for me to imagine that the massive potbellies, which sometimes appear without “bellies” or any bodies at all and, instead, take the form of disembodied heads with the same closed eyes and jowly features, had much to tell me about the rise of the earliest state-level societies in Mesoamerica, which also appeared around 300 BC. Nor, with their utter lack of hieroglyphic writing, could they reveal much about early script traditions, whose regular appearance in stone coincided with these other events. And that was my primary interest: how the imagery and themes of sculpture were critical to formulating the messages of political authority that went hand in hand with the rise of state formation in Late Preclassic Mesoamerica (300 BC to AD 250).

I began fieldwork at the site of La Blanca, Guatemala, in the early 2000s, with the hope of finding earlier sculpture that dated to the Middle Preclassic period, or between 900-600 BC. My goal was to learn more about the sculptural traditions that pre-dated the Late Preclassic period, so that I could better understand how the forms and themes of sculpture changed with the advent of state formation. Sculpture was still rare at this point in history, and particularly in this region, so I was anxious to find and document more, so that I could better understand its range and purposes. La Blanca, located 30 km from the Pacific coast in Guatemala, near the border with Chiapas, Mexico, pre-dated state formation. It was probably what we refer to as a chiefdom. It was large and had many of the hallmarks of Mesoamerican civilization, such as a 25 meter tall pyramid and many other mounds, but it lacked the centralized political and administrative systems that characterize early states. With great expectations of exploring the role of sculpture in this earlier period, I eagerly spent the summer at La Blanca, where my colleague Michael Love, a professor at California State University who directs the La Blanca Archaeological Project, had arranged to have a team of archaeologists use ground penetrating radar to help locate monuments. But none were found. That’s not a good thing if you are an art historian who works on sculpture.

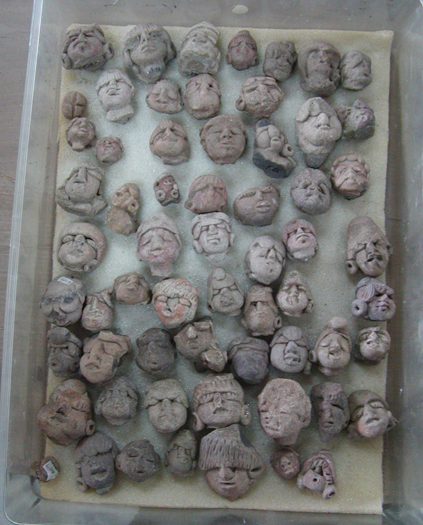

So I reluctantly began to think more broadly about what constituted sculpture for ancient Mesoamericans. What we did have at La Blanca were thousands of palm-sized ceramic figurines that are typically found in households, and that we believe were part of domestic ritual and practices of ancestor veneration. And they were everywhere. All individuals appear to have utilized figurines for ceremonies, regardless of their social rank. Both commoners and elites engaged in the same patterns of figurine use and the figurines were concrete evidence of these rituals, often conducted in the privacy of their homes. In other words, they were markedly different from the sculpture I usually look at, which is monumental, made of stone, and located in public plazas and ceremonial centers. Their context was different, their patterns of use were different, their production and distribution were different, and there were lots of them. I was definitely outside my art historical comfort zone. Albeit a bit hesitantly, I nevertheless dived in.

I quickly realized that, of the more than 5000 figurines at La Blanca, we had close to a hundred (mostly fragmentary, as we usually find them) that bore the same set of features as the potbellies and monumental heads: closed, puffy lidded eyes and jowly cheeks. At first I was confounded by this, as the ceramic figurines all came from secure archaeological contexts that dated to 900-600 BC. But the stone potbellies and massive heads only appear around 300 BC. What also intrigued me was the fact that the figurine tradition in this region waned drastically by 300 BC, when the first state-level societies emerged. In other words, with the rise of states and newly centralized political and administrative systems, the ritual activity that had characterized households during the Middle Preclassic period changed dramatically. Instead, during the Late Preclassic, the public site centers – lined by pyramids and filled with massive stone sculpture – became the new focus of ritual, carried out under the aegis of rulers. Household ritual and its attendant figurine use virtually ceased. Ironically enough, it was the disappointment of not finding monumental Middle Preclassic sculpture at La Blanca that led me to begin to think more broadly about other forms of sculptural expression, like the ceramic figurines.

I began to realize that the transition of this set of very consistent attributes – closed eyes, swollen lids, and puffy faces – from small-scale ceramics to monumental stone sculptures spoke volumes. These changes in sculpture, and the contexts in which they were used, were related to the other key social dynamics that characterized this period, such as state formation. Late Preclassic rulers appropriated the imagery and themes previously used in the domestic sector in the form of figurines and their associations with ancestors and moved them into the large, public plazas where they could proclaim their power as rulers and lay claim to their own privileged history and lineage. This imagery, which was ancient and powerful and about kinship, became a formidable tool when moved out of the hands of all and into the domain of rulers alone. The jowly facial features, the bloated bodies, and the closed eyes invoked not only dead or long-gone ancestors, but potent lineage. I also came to realize that this appropriation by newly emerging political elites attests to the complex relationship between lineage and political authority during this period.

In studying the relationship between the earlier domestic figurines and the later public potbellies and their counterparts – the massive disembodied heads — I was able to show how sculpture in ancient Mesoamerica articulated political and social issues in an era of incipient state formation. The potbellies – and their counterparts — the massive disembodied heads – quite literally gave form to the dynamics of state formation and the assertion of political legitimacy at the dawn of the Late Preclassic period in ancient Mesoamerica.

Julia Guernsey, Sculpture and Social Dynamics in Preclassic Mesoamerica

For an introduction to Mesoamerica, you can listen our interview with Ann Twinam on 15 Minute History: The Precolumbian Civilizations of Mesoamerica.

Want to read more about sculpture and Mesoamerica? Look here.

You may also like:

Stephennie Mulder, “Carved in Stone: What Architecture can tell us about the Sectarian History of Islam“

Emily Jo Cureton on Costa Rica’s ancient stone balls

Erika Bsumek, “Navajo Arts and the History of the U.S. West“