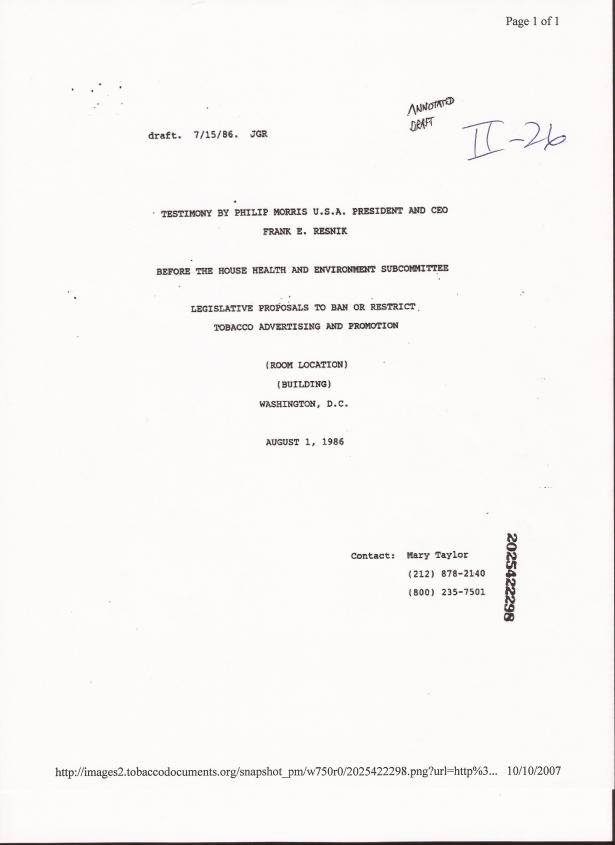

In 1998, as the a result of a court case waged by a number of US states, cities, and counties, the tobacco industry paid 42 billion dollars in damages, had to cease most forms of advertising, and had to release some 36 million pages of documents. The excerpt of a document presented here is one of those millions of private tobacco industry documents, now available online. This document comes from a case concerning cigarette advertising. In 1986 Frank Resnik, the President and CEO of Phillip Morris, testified before a US House of Representative subcommittee on “Health and Environment,” where he constructed a case for the continued “right” to advertise tobacco products. His argument was based on a rationale that called upon the still ubiquitous logic of the Cold War.

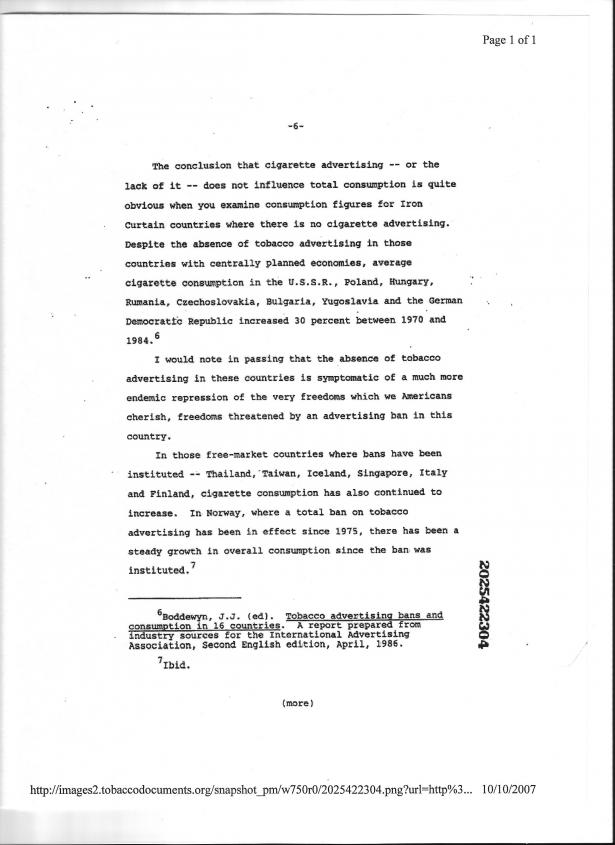

Resnik’s central argument was simply and clearly that advertising does not increase the total number of smokers in any given society; that advertising influenced smokers’ choice in terms of brand and variety, but did not increase the number of smokers overall. His primary evidence for such an argument was that behind the Iron Curtain, where there was no cigarette advertising whatsoever, cigarette consumption had increased by 30% between 1970-1984. With Cold Warriors in his audience in mind, Reznik characterizes the lack of cigarette ads in the Bloc as symptomatic of an “endemic repression of the very freedoms which we Americans cherish.”

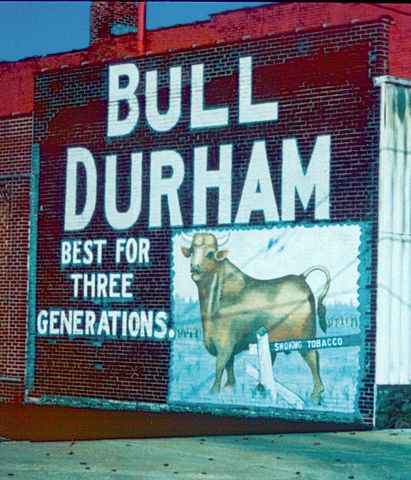

Collinsville, Illinois (photo by Lyle Kruger)

Such apparent distaste for the communist enemy, however, did not preclude American tobacco companies from engaging in lively trade in tobacco and tobacco technologies with the Eastern Bloc beginning slowly in the early 1960s with an East-West détente. By the 1970s company documents reveal an intensified interest in penetrating Bloc markets in a period when smoking rates in the United States were -2%, and communist Europe had some of the highest rates of increase, along with the “developing world.” While Russia was by far the biggest market in the Bloc, little peripheral and Soviet-loyal Bulgaria was by far the biggest producer of tobacco and cigarettes. In fact, between1966 and 1989, Bulgaria was either the largest exporter of cigarettes in the world, or second only to the US.

Cigarette Factory Workers, Pleven, Bulgaria (photo by www.lostbulgaria.com)

Cigarette Factory Workers, Pleven, Bulgaria (photo by www.lostbulgaria.com)

Bulgaria became one of the most important points of entry for Phillip Morris, RJ Reynolds, and other US tobacco companies to penetrate the Iron Curtain into a growing and untapped market. While the direct imports of cigarettes into the Bloc remained limited, Bloc states signed licensing agreements with US companies in the mid-1970s that resulted in the production of Marlboro (Phillip Morris) and Winston (RJ Reynolds) in local factories. These “American cigarettes” were highly seductive to local consumers, as other Western products that were largely available in hard currency stores or carried across the border in suitcases by the lucky few who could travel to the West. If Bulgarians and other Bloc citizens could not go to America, they could at least hold its glossy packaging in their hands, and inhale its particular blend of taste and nicotine that was quite distinct from the Bulgarian “Oriental” variety. In the late communist period, American cigarette brands perforated the Iron Curtain in a sustained and successful way, paving the way for a post-communist flooding of local markets.

But Resnik, of course did not mention such facts at the 1986 session of the House Health and Environment committee. He did not mention that with the leveling off of US markets the communist world had become an explicit target of tobacco trade and that the industry had been among the first to push US entry into these markets. Instead he called upon the House committee members as freedom-loving Americans to reject all legislative proposals to ban or restrict tobacco advertising. By 1986, however, the industry was rapidly losing ground to an organized and effective grass-roots anti-smoking movement. As of August 1986, tobacco ads were no longer allowed to appear on TV. Yet in the Eastern Bloc, where ads had never been on TV, smoking rates continued to rise among men, women, and youth. Perhaps Reznik was right in saying that advertising had no role in increased smoking rates, rather smoking was a by-product of communist modernization projects, with their accompanying new modes of leisure and consumption.

The rapid rise in smoking in the Bloc eventually raised concerns about tobacco and health, and Bloc states have waged fairly serious anti-smoking campaigns since the 1970s. Such campaigns, however, were largely ignored by local populations. Anti-smoking came from the wrong messenger, and what little “freedoms” people had – like an afternoon smoke break—were held onto tightly. Hence unlike the United States, communist citizens were largely resistant to the anti-smoking campaigns that stopped smoking as a mass consumer phenomenon in the West in its tracks. To this day, the former communist states (and still-communist China) have among the highest smoking rates in the world. While the Western cigarette easily seduced (and still seduces) these populations, the Western propensity to kick the habit is more contested. As Frank Reznik might have once interpreted it, the “right” to smoke is still valued by people from large swaths of the globe, particularly the lands once (or still) ruled by communists.

Watch for our November feature on Mary Neuburger’s new book, Balkan Smoke: Tobacco and the Making of Modern Bulgaria