By Madeline Hsu

Both of the books I have written originate with family stories. When I was unable to recognize my parents’ and grandparents’ experiences in standard histories of migration and Chinese Americans, I began digging for more information so I could develop the narratives of their lives on my own. My first book, Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration between the United States and Southern China, 1882-1943, drew upon my personal knowledge. Standard depictions of Chinese Americans during the 1920s and 1930s represented them as groups of dysfunctional bachelors stuck in service sector jobs such as laundries and restaurants. My maternal grandfather might have seemed a typical Chinatown “bachelor” to the casual observer, but his story was more complicated. He arrived in the United States as a teenager in the 1920s to help his father run a grocery store serving African American customers in a small town in rural Arkansas. In the mid 1930s he returned to China, married my grandmother, fathered my mother, and then when money fell short, returned to Arkansas alone due to restrictive immigration laws. On his own and at a distance, he was providing for his family back home.

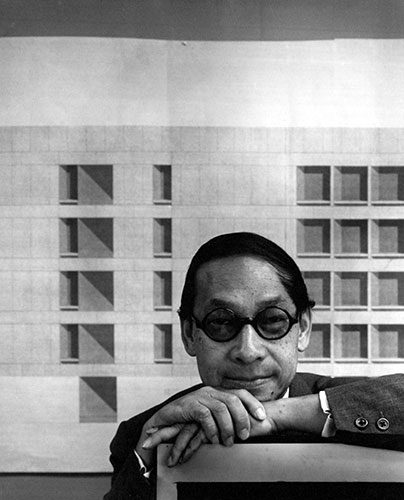

Sketch on board the steam-ship Alaska, bound for San Francisco. From “Views of Chinese,” The Graphic and Harper’s Weekly, April 29, 1876

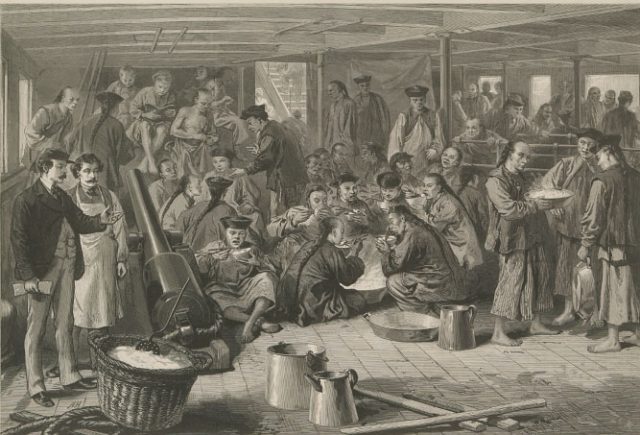

My grandfather’s story led me to uncover the largely overlooked reality that about 25 to 40 percent of Chinese men living in the United States before World War II were also long-distance husbands and fathers, although to most Americans they looked like non-assimilating oddities living communally with other perpetually single men. Situating such lives in the transnational context of the families and communities that they supported in China, often at great personal sacrifice, gives meaning to the hardships endured by Chinese American “bachelors” who were sharply constrained by open discrimination and the most severe of immigration restrictions during what is known as the Chinese exclusion era (1882-1943).

“We must draw the line somewhere, you know.” Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper, vol. 54 (1882 April 1).

My second book, The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority traces my father’s immigration story, which also departed from standard narratives. My father arrived for graduate studies in chemical engineering in 1960. Then he managed to convert from student status and gain permanent residency rights, as did over 90 percent of his contemporaries from Taiwan. Although the immigration of educated, professional Asians has become commonplace, this change in migration patterns is usually attributed to the 1965 Immigration Act and its occupational preferences, too late to explain what happened with my father.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Immigration Act, October 3, 1965. (U.S. National Archives, Identifier 2803428)

Seeking answers led me to uncover the longer roots of privileged migrations by Chinese students and intellectuals. I found that even in the throes of the Chinese exclusion era, when most Chinese were barred from entering the United States, could not gain citizenship by naturalization, and lived under some of the most segregated of circumstances if they did gain entry, educated Chinese were welcome on university and college campuses and among internationalist circles that included leaders from foreign policy makers and influential foundations. From the 1910s through the 1930s, Chinese were always among the most numerous of international students in the United States. In fact, many of the foundations of international education policies and institutions developed to secure their educational access and success.

Unlike their working-class counterparts, who were seen as unwanted labor competition and incapable of sharing American democratic values, Chinese intellectuals were seen as members of China’s leadership class and culturally compatible. Educating them in the United States was a friendly, inexpensive, yet effective means of extending American influence over China. These hopes of setting China on the path to American-style democracy and Christianity were most potently embodied by Madam Chiang Kai-shek, the Methodist, U.S. educated (Wellesley 1917) wife of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek who led China from 1927 until 1949. Many less famous, U.S.-educated Chinese also played instrumental roles in establishing the foundations of modern education, professional standards and practices, and government bureaucracies in China.

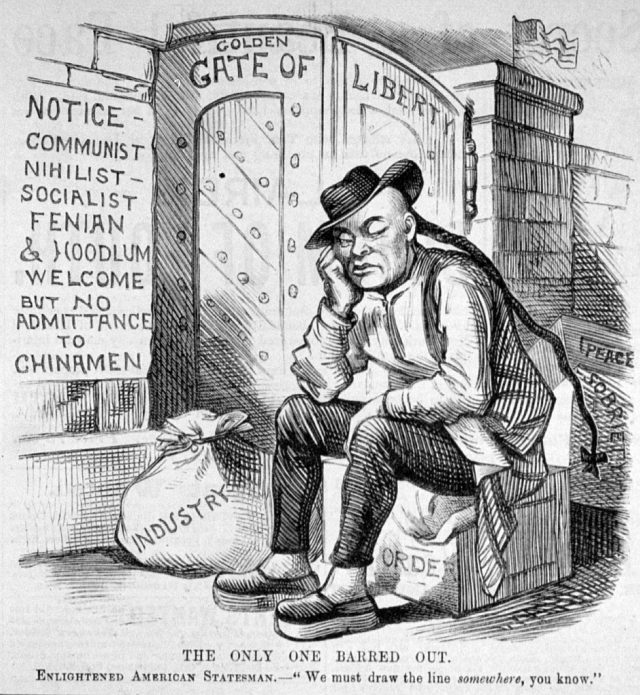

World War II and the Cold War transformed the relationship of Chinese students to the United States by turning them into refugees unable to return to their war-torn, and then communist, homeland. In the case of these well-educated, highly acculturated, and usefully skilled Chinese elites, the international education establishment, State Department, Department of Labor, and Congress found that they could make accommodations to facilitate their remaining in the United States and finding gainful employment. Congress took the unprecedented step of allocating about $10 million to enable the so-called “stranded students” to complete their graduate programs, legally gain employment, and then, through stopgap measures, gain legal permanent residency. Such steps made possible the immigration of such notable Chinese Americans as the architect I.M. Pei and the computer entrepreneur An Wang.

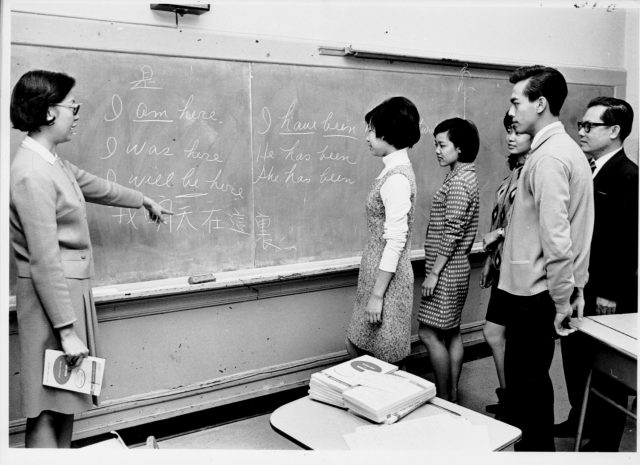

An English class for Asian American ILGWU members of Local 23-25, December 15, 1968 (via Kheel Center on Flickr)

Although numbering only about 12,000, the “stranded students” represented a significant shift in U.S. views of immigration laws and policy that gained force in the two decades leading up to 1965. They demonstrated the benefits of prioritizing economic concerns such as employability and skills in immigration restrictions, rather than the then current law’s primary emphasis on race and national origins which was proving a tremendous stumbling block to foreign policy and retention of the most valued of knowledge workers. If not for such special programs, both Pei and Wang would have been forced to depart the United States.

President and Nancy Reagan at the Opening Ceremonies of Liberty Weekend with medals of liberty recipients Henry Kissinger, Franklin Chang-Diaz, I.M. Pei, Itzhak Perlman, James Reston, Kenneth Clark, Albert Sabin, An Wang, Elie Wiesel, Bob Hope, Hanna Holburn, Lee Iacoccaat Governors Island, New York, July 3, 1986.

Pressures for immigration reforms grew after World War II, as did the numbers of international students with encouragement from the State Department, expanding university systems, and research labs and facilities eager to hire the most talented workers in STEM fields. Provisional measures allowed these international students, many from Taiwan, Hong Kong, India, and South Korea, to work and remain in the United States, until the 1965 Immigration Act permanently enshrined these preferences in law. Since then, a majority of Asian immigrants arriving under its terms have been disproportionately college-educated and based in STEM fields, contributing to the model minority image so much associated now with Asian Americans.

My grandfather and my father don’t appear in my books, but their experiences inspired my research and infuse my broader historical narratives with the gradations of both loss and recuperation characteristic of migrant lives.

Books by Madeline Hsu:

The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority (2015)

To read more about Asian American immigration, look here.

You can also hear Madeline Hsu on 15 Minute History.

Top photo credit: Chinese students at MIT, 1944. Courtesy Donald and Sylvia Tsai.