by Joseph Parrott

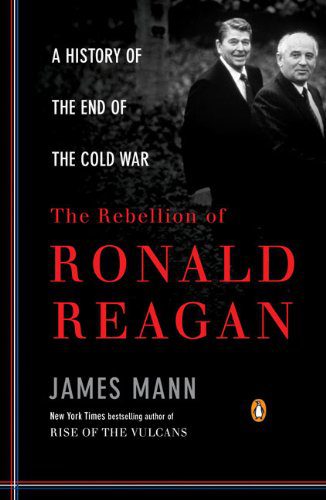

Ronald Reagan’s presidential policies have irrevocably shaped the political debate over the last two decades. He effectively reversed the momentum of the New Deal expansion of the federal government while leading the largest growth in peacetime military spending in national history, making him a polarizing figure for commentators and historians alike. Contrasting visions of Reagan have been especially stark in the realm of foreign affairs. Advocates often argue that he launched a new arms race that undermined the Soviet Union. Critics remember a detached leader presiding over the shameful Iran-Contra scandal. Both depictions are problematic, as they accentuate different aspects of a complex, often inscrutable man. Therefore, James Mann’s examination of the president’s personal diplomacy with the Soviet Union is especially welcome. The journalist has written critically of conservative foreign policies in the past, but he finds much to admire in Reagan. No, the president did not single-handedly end the Cold War, nor was he the primary factor influencing its peaceful resolution. According to Mann, he was, however,  optimistic and adaptable, relying on a set of Cold War values that emphasized the human character that existed under the communist system he so vehemently despised. These values ran counter to entrenched ideologies on both right and left, but they allowed him to see the promise of working with honestly reform-minded Mikhail Gorbachev.

optimistic and adaptable, relying on a set of Cold War values that emphasized the human character that existed under the communist system he so vehemently despised. These values ran counter to entrenched ideologies on both right and left, but they allowed him to see the promise of working with honestly reform-minded Mikhail Gorbachev.

Mann finds the key to Reagan’s rebellion in his particular moralistic perspective on the Cold War conflict. The president believed that the United States was a country of right, where democracy and capitalism best served the needs of the people. In contrast, Reagan viewed communism as a devious ideology imposed on an unwilling nation by disingenuous leaders. This Manichean approach to the political systems often made him aggressive and overbearing, inspiring his rhetoric of the “evil empire” and his unbending attachment to the “Star Wars” missile defense system. However, Mann argues that this separation of the people from the system also allowed for a certain flexibility. Reagan saw a real possibility for systemic reform if only a Soviet leader would abandon dictatorial control of the people. Mann contrasts this ideological worldview with the seemingly more moderate one held by the realist architects of détente, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. The duo embraced a rigid model of geopolitical competition where the existence of two superpowers with contrasting ideologies made some conflict inevitable. Power relationships, and not specific leaders, fueled the feud. Managing the conflict through persistent pressure offered the only solution. Due to his faith in a laudable human side to the Soviet state, Reagan broke with his own party’s thinking. He embraced Gorbachev when he came to trust the man, moderating his suspicion of the Soviet actions in a way critics like Nixon could not understand.

This interpersonal relationship is Reagan’s lasting contribution to decreasing tensions. Mann makes this argument by examining a series of key moments in Reagan’s presidency. When Gorbachev first came to power, Reagan remained hawkish and distrustful of the new leader. The arch-Cold Warrior eventually warmed to the Soviet premier thanks partly to the intervention of popular author and Russophile Suzanne Massie and to the face-to-face meetings at Reykjavik and Geneva. Certainly, Reagan never fully abandoned his confrontational tone, perhaps best exemplified in his direct challenge to Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall. Still, Mann considers even this a positive quality, as Reagan continued to push Gorbachev to make good on his opening of the Russian political system and the liberalization of its foreign policy.

President Reagan meeting with Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev for the first time during the Geneva Summit in Switzerland, 1985 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

There is room for debate in some of these conclusions, but Mann shows clearly the key role of Reagan in keeping dialogue going after the initial summit meetings. Nixon, Kissinger, and even advisers like Frank Carlucci rightly believed that Soviet reforms were meant primarily to strengthen the country, yet in their support for more confrontational policies they missed the real potential of cooperation. The president was almost alone in his belief in the sincerity of Gorbachev’s calls for reduced tensions and the decisive role collaboration could play in positively shaping global politics. The president could not have predicted the rapid dissolution of the communist bloc or the Soviet Union, but he “grasped the possibility that the Cold War could end” and he sold this hope to a wary country over the objections of his own political party.

Ronald and Nancy Reagan greeting Moscow citizens during the Moscow Summit (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Mann’s eminently readable book demythologizes Reagan, but it also celebrates his lasting if perhaps unpredictable contribution to ending the world’s most dangerous international conflict. Mann agrees with recent authors like historian Melvyn Leffler that Gorbachev’s actions lead to the peaceful resolution of the Cold War, though the Soviet premier does not take center stage. Reagan’s role was as the willing dance partner. Reagan was a hawk, but he was far less hidebound in his beliefs than many of his contemporaries. The president pursued the opportunity to reduce tensions when it presented itself. In a time when politicians from across the political spectrum are retreating into bunkers of partisanship, Mann is right to celebrate Ronald Reagan’s decision to ignore the party line.