Fidel Castro had two political assets that enabled him to stay in power for a half century. He possessed the knack of turning adversity into an asset and he knew his enemies, particularly the anti-communist politicians of Washington, D.C. His guile and skill became evident early on as he established his revolution under the gaze of Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy.

Upon taking control of the Cuban military with his guerrillas acting as the new officer corps, he set out in January 1959 to bring to justice the thugs and killers of the old regime. He ordered Che Guevara in Havana and Raúl Castro in Santiago de Cuba to establish revolutionary tribunals to judge the police and army officers for past human rights abuses. In all, some six hundred convicted men faced the firing squads in a matter of months.

Fidel also instructed the US military mission to leave the country. He accused it of teaching Batista’s army how to lose a war against a handful of guerrillas. Cuba no longer needed that kind of military training, Castro said. “If they are going to teach us that, it would be better that they teach us nothing.”

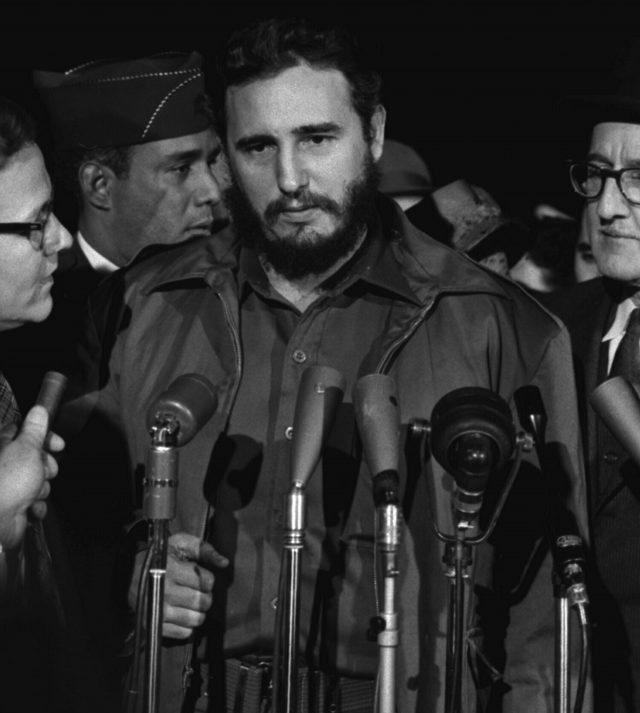

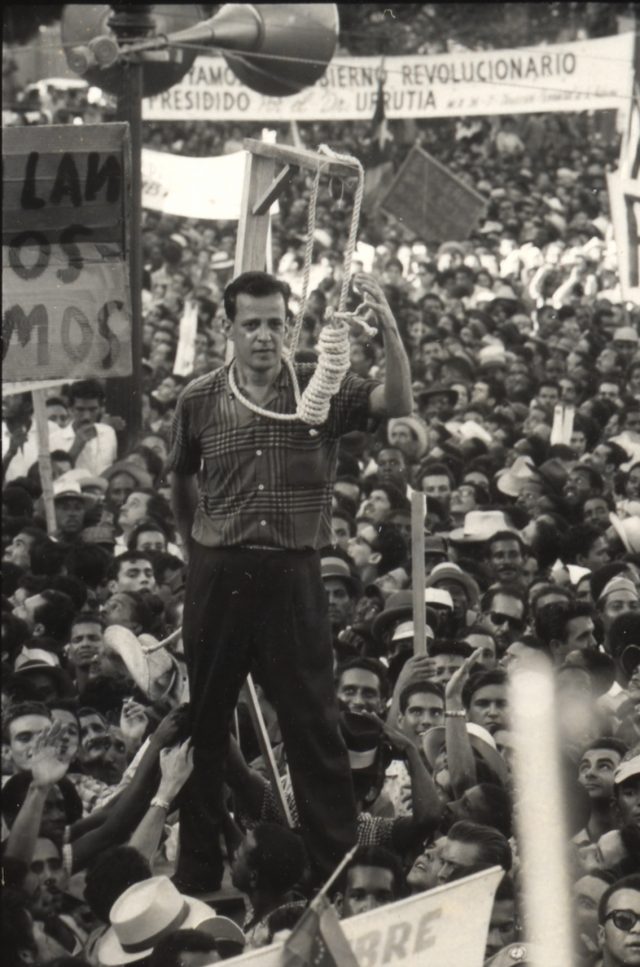

Castro supporters in Havana joke about US criticism of the executions of Batista’s “war criminals.” (via author)

Cubans applauded these procedures as just retribution for the fear and mayhem that Batista’s dictatorship had caused. But American newspaper editors and congressional representatives condemned the executions as revolutionary terror. Fidel used this criticism to rally his followers. Where were these foreigners, he asked, when Batista’s men were snuffing out “the flower of Cuba’s youth?” Soon thereafter, the guerrilla comandante became the head of government as prime minister.

In his trip to Washington in April 1959, Castro endured the constant questions from reporters about communists showing up his new regime. President Eisenhower found it inconvenient to be in Washington when the new Cuban leader arrived. He arranged a golf game in Georgia, leaving his vice president to meet with the visiting prime minister. It was not a meeting of the minds. Richard Nixon and Fidel Castro differed on just about every subject: the communist threat, foreign investment, private capital, and state enterprise. The vice president tried to inform the new leader about which policies would best serve his people, and he ultimately described the unconvinced Castro as being naïve about communism. Unbeknownst to the CIA, the first Cuban envoys were already in Moscow requesting military trainers from the Kremlin.

Then in the summer of ’59, Fidel began the agrarian reform project by nationalizing plantation lands owned by both Cuban and US investors. Without any fanfare whatsoever, communists took control of the new agency that took over sugar production. Chairman Mao sent agrarian technicians to act as advisers. The US embassy in Havana demanded immediate compensation for dispossessed American owners. Instead, they received bonds due in twenty years.

Fidel knew how to provoke yanqui reactions in ways that exposed the big power chauvinism of Washington. He hosted Soviet officials and concluded a deal to take on supplies of Russian crude petroleum. Castro asked the American-owned refineries to process the oil into gasoline, which the State Department advised them not to do. Castro had his excuse to confiscate the refineries.

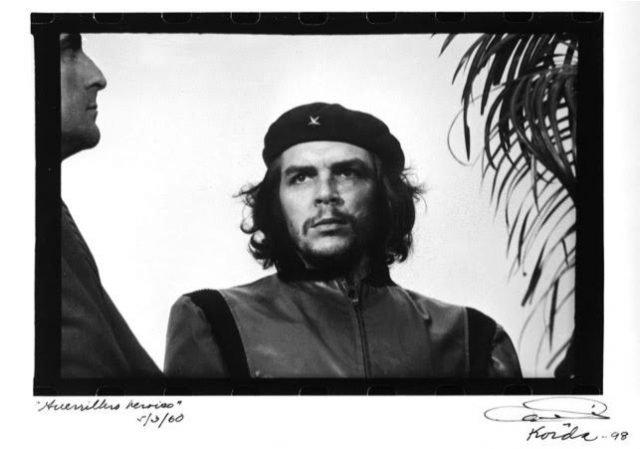

A French ship filled with Belgium weapons arrived in Havana harbor in March of 1960. It exploded and killed 100 Cuban longshoremen. Castro rushed to the TV station and denounced the CIA for sabotaging the shipment. He gave a fiery anti-America speech at the funeral service in the Plaza of the Revolution to which a host of left-wing personalities flew in to attend. Simone Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre arrived from France, Senator Salvador Allende came from Chile, and ex-president Lázaro Cárdenas traveled from Mexico. At this event, Fidel introduced his motto “Fatherland or death, we will overcome,” and the Cuban photographer Alberto Korda took the famous image of Che Guevara looking out over the crowd.

At that point that President Eisenhower ordered Director Allen Dulles of the CIA to devise the means to get rid of Castro’s regime in which Washington’s “hand would not show.” Agents attached to the US embassy in Havana contacted Catholic and other youth groups who objected to Fidel’s communist friends. They received airline tickets to leave the country and salaries to train as soldiers in Guatemala. Fidel had spies in Miami and Central America sending him progress reports on the émigré brigade in training. Now he had Eisenhower’s diplomats on the defensive. They had to deny Castro’s accusations about an upcoming CIA invasion.

In the meantime, Castro announced plans to socialize the economy, a project that Che Guevara headed up. What was the White House to do? The 1960 election had swung into full gear. The Democratic challenger in the first presidential debates famously said that he was not the vice-president who presided over the communist takeover of the island just 90 miles offshore from Key West. Eisenhower responded with toughness. He lowered the amount of sugar the United States imported from Cuba, and Fidel seized upon this provocation to nationalize the remaining US-owned properties, especially the sugar refineries.

By now, the exodus of Cuba’s professional classes had been expanding over the preceding year until it reached a thousand persons per week. Middle-class families formed long lines outside the US embassy in order to obtain travel visas. President Eisenhower appointed Tracy Voorhees, the man who handled the refugees from the 1956 Hungarian Revolt, to manage the resettlement. He established the Cuban Refugee Center in Miami. A mix of American charities and government offices sponsored evacuation flights, housing, job-hunting services, emergency food and clothing drives, educational facilities, and family subsidies. Let them go, Castro told his followers. He called the refugees gusanos (worms), the parasites of society.

Castro benefited from such American interference. It cost him nothing to get rid of his opponents, especially as the US taxpayers footed the bill. He utilized the former privilege of these gusanos to recruit peasants and workers to the new militias. The huge military parade on the second anniversary of the Revolution in January 1961 featured army troops with new T-130 tanks and army units armed with Czech weapons. Thousands of militiamen marched with Belgium FAL assault rifles.

He did not shut down the American embassy but utilized Soviet-trained security personnel to monitor the activities of diplomats and CIA men. He waited until the Americans severed diplomatic ties in order to be able to pose as the victim of US malice. Eisenhower severed diplomatic relations with Cuba to spare the new president, John F. Kennedy. Anyway, the new president very soon would have to preside over the CIA-planned invasion of the émigré brigade whose coming Castro was announcing to the world.

Now the anti-communist onus had passed to Kennedy. He could not shut down the CIA project and return hundreds of trained and irate young Cubans to Miami. Neither could he use American military forces to assist the invasion. Nikita Khrushchev had already threatened to protect the Cuban Revolution with “Soviet artillery men,” if necessary. Also, citizens in many Latin American nations took pride in Cuba’s defiance of US power. Kennedy too was trapped by his own anti-communist bravado during the election campaign. He changed some of the plans and let the invasion proceed.

The Bay of Pigs landing of April 1961 turned into a disaster. A bomber assault by exile pilots on the Cuba revolutionary air force failed to destroy all of Castro’s fighter planes. The few remaining fighters chased the bombers from the skies and sank the ships that brought the brigade to shore. The fourteen hundred émigré fighters killed as many militiamen as possible before they ran out of ammunition on the third day. Castro put 1200 of the surviving exiles in jail. In the meanwhile, neighborhood watch groups in Havana and other cities cooperated with state security personnel in rounding up thousands of potential opponents, most of whom were processed and returned home in due course.

Che Guevara summed up the result of the Bay of Pigs when he “accidentally” met up with White House aide Richard Goodwin at an OAS meeting in Uruguay. Please convey our thanks to your president for the Bay of Pigs, Che said. “The Revolution is even more ensconced in power than ever because of the US invasion.”

More by Dr. Jonathan C. Brown on Not Even Past:

The Future of Cuba-Texas Relations

Capitalism After Socialism in Cuba

A Rare Phone Call from One President to Another