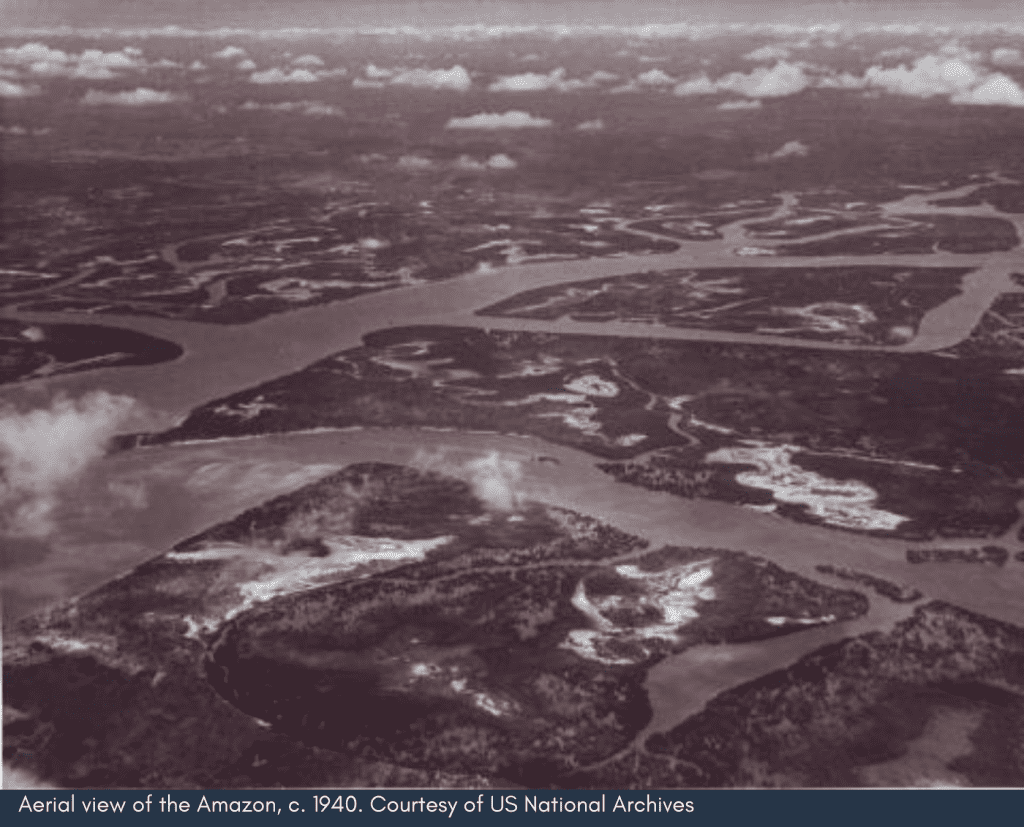

At 2,700,000 square miles, the Amazon Basin is three-quarters the size of the continental United States, and a million square miles larger than all of Europe exclusive of Russia. Covering two-fifths of South America and three-fifths of Brazil, the Amazon Basin contains one-fifth of available fresh water in the world, one-third of evergreen broad-leaved forest resources, and one-tenth of the world’s living species. The Amazon river, the longest in the world (at 4,255 miles), has some 1,100 tributaries, seven of which are over 1,000 miles long.

And the Amazon’s forests, along with the adjacent Orinoco and Guyanas, represent over half the world’s surviving tropical rain forests. While contemporary accounts of the Amazon often begin by rattling off such statistics to provide readers with seemingly definitive answers, I raise them to make a fundamental point about the region. The Amazon is often imagined as a pristine, and increasingly endangered, realm of nature, but it should be seen as a region that has been constructed by public policies, social mediators, and cultural representations that operate at multiple scales: local, national, and global.

During World War II, the governments of Brazil and the United States made an unprecedented level of joint investment in the economy and infrastructure of the Amazon region. The dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas (1937-45) trumpeted the colonization and development of the Amazon (christened the “March to the West”) as a nationalist imperative to defend a sparsely settled frontier covering some sixty percent of Brazilian territory. The Vargas regime subsidized labor migration and agricultural colonization, modernized river transportation, and rationalized rubber production in The Amazon. These fledgling efforts were given an unexpected boost when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and subsequently invaded the Malayan peninsula and Dutch East Indies, which deprived the United States of more than 92 percent of its rubber supply.

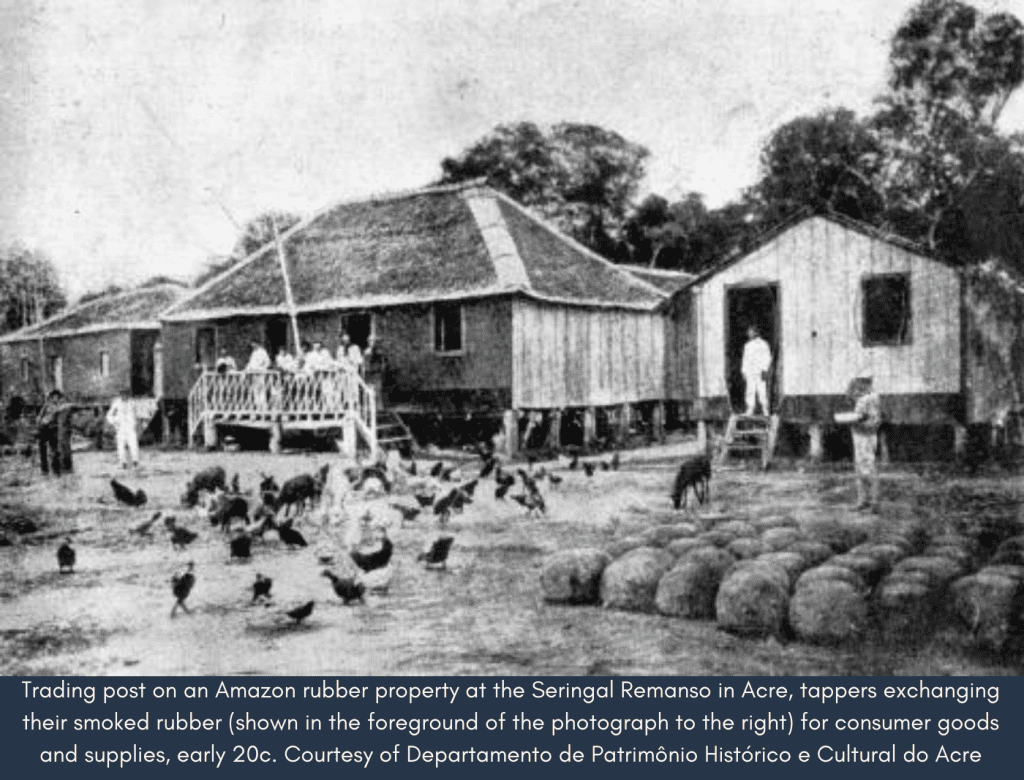

Unlike other types of tropical flora, rubber was indispensable for modern warfare, ensuring the mobility, speed, and efficiency critical for military defense. The United States, which consumed more rubber than the rest of the world combined in 1940, was dependent on Southeast Asian rubber sources, having failed to develop a synthetic rubber industry, or diversify its sources of natural rubber, or stockpile in preparation for emergencies. In 1942, Brazil agreed to sell its surplus rubber to the United States for a fixed rate for five years. The United States, in turn, invested millions of dollars in health and sanitation programs, public finance, and the relocation of tens of thousands of migrant workers from Northeastern Brazil to tap rubber in the Amazon.

In the context of binational wartime mobilization, a host of new (or renewed) claimants on Amazonian resources and populations emerged. Agronomists, sanitarians, physicians, botanists, engineers, technicians, army officials, intellectuals, consumers, migrant workers, and the media all became involved in Amazonian development. As Earl Parker Hanson noted in 1944: “It is probable that the past two years have seen more actual exploration of the basin, more knowledge gained about its physical nature than have all the four centuries since that early conquistador, Francisco de Orellana, was the first white commander to traverse it.”

Despite wartime pronouncements exhorting the peoples of Brazil and the United States to join in battle against the Axis and the forest, the Amazon’s vast territory, varied natural resources, and charged ideological significance precluded any uniform ideas or policies. National interests and cultural biases often divided people despite shared professional backgrounds or technocratic mindsets that might have united select Brazilian and U.S. policy makers in their efforts to develop the Amazon. Headiness marked an economic boom, but rubber tappers and their bosses jousted over revenues and resources, while migrants pursued varied livelihoods in the region.

Today the landscape of the Amazon reflects the legacy of such wartime tensions and transformations. The creation of Brazilian banking and public health institutions, alongside the expansion of airfields and transportation infrastructure, heralded the postwar advance of capital markets and state consolidation in the region. Mass wartime migration from Northeastern Brazil contributed to the region’s rapid demographic growth and urban expansion. Forest populations’ maintenance of traditional patterns of extraction, slash-and-burn agriculture, hunting, and fishing preserved tropical ecosystems and systems of local knowledge. And the U.S. development of a domestic synthetic rubber industry by 1944-45 redirected postwar foreign investment in the Amazon from the wild rubber trade to mineral extraction. The history of wartime Amazonia also illustrates the shifting appropriation of the region’s resources. The Amazon’s reincarnation as ecological sanctuary resulted not only from postwar deforestation, but the rise of a global environmental movement, the emergence of new fields of scientific inquiry, and the grass roots mobilization of forest dwellers.

By melding the concerns and approaches of environmental, diplomatic, labor, economic, and social history, we can see Amazonian landscapes and lifestyles as the products of ecological, material, and political forces that a competing set of social mediators brought to bear on the meanings and uses of nature. This little known chapter of World War II history illuminates the ways outsiders’ very understandings and representations of the nature of the Amazon have evolved over the course of the latter half of the twentieth century.

Seth Garfield, In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of a Region.

John Tully, The Devil’s Milk: A Social History of Rubber (2011).

In a social history that spans several centuries and continents, John Tully chronicles the central role of rubber in shaping the modern world through its multiple uses in industrial machinery and consumer goods, as well as its devastating toll on the global workforce that has produced and manufactured it.

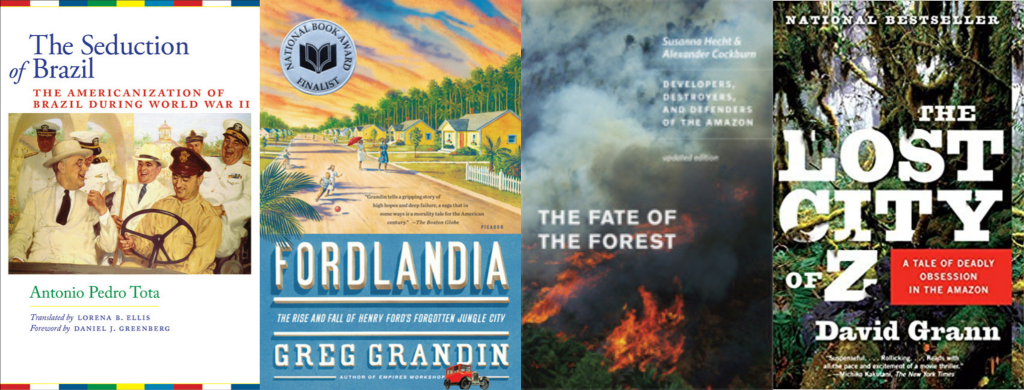

Greg Grandin, Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City, (2009).

A finalist for the Pulitzer prize, Fordlandia chronicles how Henry Ford’s megalomaniacal efforts to create rubber plantations and a model American-style company town in the Amazon— to circumvent the British and Dutch colonial Asian monopoly in supplying tires for his automobiles—was doomed by hubris and ignorance toward Amazonian ecosystems and social mores.

Susanna B. Hecht and Alexander Cockburn, The Fate of the Forest: Developers, Destroyers, and Defenders of the Amazon, (2011).

A sweeping, historically-informed account of the Amazon that traces the longstanding and varied efforts by outsiders to transform human populations and natural landscapes in the region. The period of authoritarian rule (1964-85) is particularly spotlighted as a watershed in the destructive development of the Amazon: Brazil’s military government, guided by geopolitical doctrines and alliance with both industrial capital and traditional oligarchs, spearheaded highway construction and population resettlement, subsidized the expansion of cattle ranching, and oversaw vast mining operations which would have highly deleterious consequences for the natural environment and traditional populations.

Antonio Pedro Tota, The Seduction of Brazil: The Americanization of Brazil During World War II ,(2009).

The cultural politics of the Good Neighbor Policy undergirding the Brazilian-American alliance during World War II are explored in this diplomatic and cultural history by Brazilian historian Antonio Pedro Tota. While primarily focused on the public relations activities of Nelson Rockefeller’s Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs — established in 1940 and tasked with improving U.S. relations with Brazil and other Latin American countries — the book underscores the agency of Brazilian officials in selectively adopting or adapting wartime programs and propaganda for nationalist ends.

David Grann, The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon, (2009).

The unsolved mystery of the disappearance of British explorer Percy Fawcett and his son in the Amazon in 1925, while in search of an ancient lost city, is delightfully recounted by journalist David Gann in an account that blends the genres of biography, detective novel, and travelogue. Fawcett’s “personal” obsessions are historically contextualized within an age of Victorian exploration, scientific racism, and the enduring allure of the Amazon as El Dorado. Although the book’s suspenseful climax does not resolve the enigma surrounding Fawcett’s death, it does suggest that the explorer may ultimately not have been misguided in pursuing the remnants of a great cultural civilization in the Amazon.

Cinema, Aspirins, and Vultures, (2005). Directed by Marcelo Gomes.

Set in the parched backlands of Northeastern Brazil in 1942, this poignant Brazilian feature film captures the historical saga of hundreds of thousands of residents of the outback confronting natural disaster, economic privation, wartime nationalism, and newfound opportunities to tap rubber in the Amazon, by following the personal odysseys of a German pharmaceutical salesman and a drought refugee.

You may also like:

Cristina Metz’s NEP review of Greg Grandin’s Fordlandia

Elizabeth O’Brien on labor history in the sugar industry in Brazil

Eyal Weinberg on labor history in Sao Paulo

Darcy Rendón on the social history of the lottery in Brazil

Photo Credits:

Hydroplane used by the Rubber Development Corporation, a U.S. government organization delivering tapping supplies and foodstuffs to upriver locations during WWII. Courtesy of US National Archives.