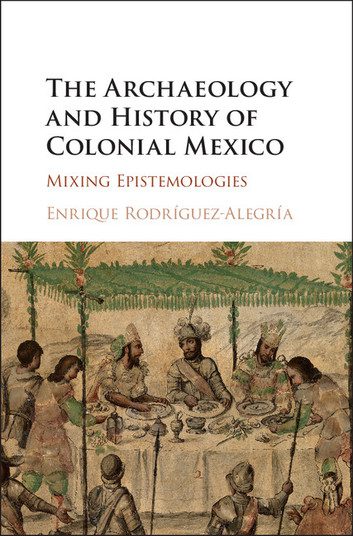

In this study of the social significance of material culture in Mexico City and Xaltocan in the early colonial period, Rodriguez Alegría uses a variety of sources, including archaeological evidence relating to food consumption, catalogues of ceramic sherds from several dig sites in these cities, and wills, stock lists, and auction records. His use of archaeological data and historical records together reveals the benefits of incorporating disparate kinds of evidence: the archaeological data on food and material consumption filled in the blanks of historical records, which often leave out explicit descriptions of such daily practices.

The works of historians and anthropologists frequently overlap in theme and subject, however, the two disciplines gather and use evidence differently. Rodríguez Alegría argues that such differences should not stand in the way of interdisciplinary investigations. His main contribution is a discussion of the ways scholars conceptualize their methodologies. He asserts that in an interdisciplinary study, there should not be a contest over which kind of evidence is more worthwhile. Rather, researchers should pay careful attention to the implications of the interpretative strategies they use.

Part of what makes his methodology innovative is his acceptance of the inherent incommensurability of archaeological and historical evidence. He outlines common interpretative strategies used in each of these disciplines, openly acknowledging the differences between them. For archaeologists, analogical reasoning is common because it allows them to utilize “known behaviors in the present” in order to shed light on “unknown behaviors [of] the past.” Historians, on the other hand, tend to conceptualize evidence from their documents as synecdoches, “where qualities or practices found in a document or a few documents are replicated to stand for wider processes or patterns in a society.”

In his openness to the contradictions that result from simultaneously using these distinct methods, Rodríguez Alegría creates a provocative rejection of the established practice of seeking an uncontested line of reasoning. He asserts that the incorporation of more evidence fundamentally creates a more nuanced understanding, even if all the pieces do not come together to neatly form a single image. As a result, both the synecdoche favored by historians and the analogy used in anthropology have their place in a single work.

Rodríguez Alegría provides numerous examples of the benefits of interdisciplinarity, including his illustration of how quantitative and qualitative analysis of pottery fragments combine with historical data on markets and production methods to reveal new understanding of of the role of pottery in these cultures. In that sense, the writing and presentation style achieves the important goal of encouraging cross-disciplinary understanding.

The most compelling aspect of this work is the author’s insistence that scholars redirect their attention towards a more critical analysis of how they interpret their evidence. Forcing this awareness about discipline-determined approaches to data analysis promises new insights, but it also presents potential problems. At some point, scholars have to assert a coherent narrative, or at least a conceptual image, of the phenomenon under investigation. That process inherently requires a selection of relevant information. If scholars choose to incorporate apparently contradictory data collected outside of their discipline, they could face criticism for knowingly promoting an argument that goes against some of the data. It is possible that the scholarly community as a whole would resist this approach because of the widely ingrained attachment to uncontested narratives that Rodríguez Alegría criticizes.

This work prompts an important reexamination of disciplinary divisions and approaches to the interpretation of evidence. It fundamentally brings the question of what makes a document representative of a larger phenomenon to the forefront of historical analysis. Furthermore, it encourages scholars to think about how their investigation engages with contextual information from unwritten sources. Overall, Rodríguez Alegría’s book opens up an important discussion on the value of questioning the validity of even the most standardized interpretive strategies. As he points out, establishing a narrative is fundamental for historians because of its apparent utility in illustrating change over time. It is also, however, a method that reflects our aesthetic preference for presenting information this way. Both historians and anthropologists must, therefore, aim to break down barriers that would prevent the fruitful sharing of methodologies between disciplines.

Also by Brittany Erwin on Not Even Past:

The Museo Regional de Oriente in San Miguel, El Salvador

The National Museum of Anthropology in in San Salvador

You may also like:

Haley Schroer reviews Infrastructures of Race: Concentration and Biopolitics in Colonial Mexico by Daniel Nemser (2017)

Explore Diana Heredia’s virtual exhibition “Of Merchants and Nature: Colonial Latin America through Objects”

Ann Twinam reviews No Mere Shadows: Faces of Widowhood in Early Colonial Mexico by Shirley Cushing Flint (2013)