By H. W. Brands

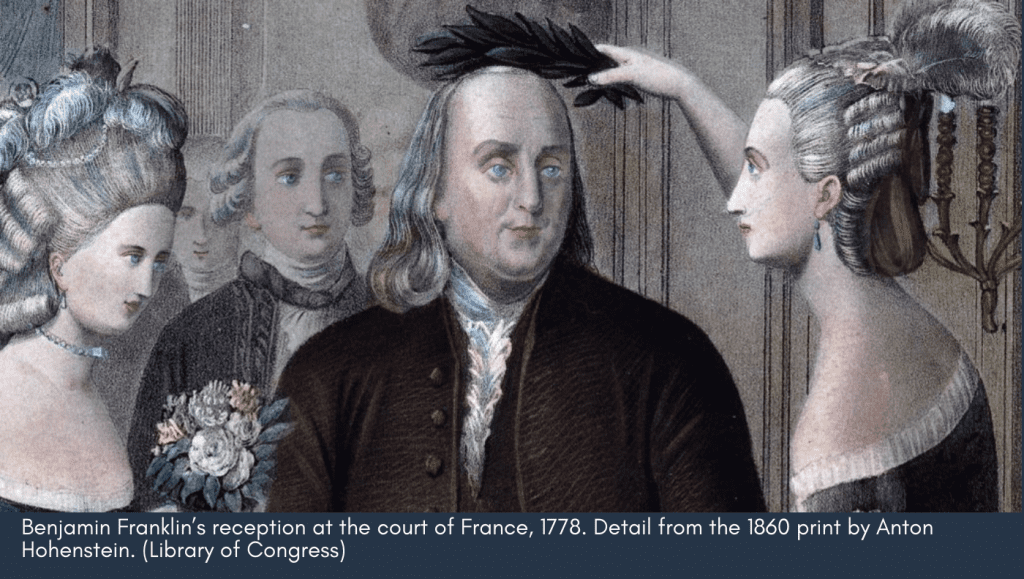

When Benjamin Franklin left the Constitutional Convention in September 1787, he was approached by a woman of Philadelphia, who asked what the deliberations of Franklin and his colleagues had given the young nation. “A republic,” he said, “if you can keep it.

Henry Clay was ten years old that summer. He didn’t learn of Franklin’s challenge till later. But when he did, he discovered his life’s work. Clay and others of the generation that followed the founders confronted two problems in particular–two pieces of public business left unfinished in the founding.

The first was the awkward silence of the Constitution on the fundamental question of the federal system: when the national government oversteps its authority, how is that government to be restrained? Must the states obey laws they believe to be unconstitutional? Put most succinctly: where does sovereignty ultimately lie–with the states or with the national government?

The second problem was the contradiction between the equality promised by the Declaration of Independence and the egregious inequality inherent in the constitutionally protected institution of slavery. Thomas Jefferson’s assertion that “all men are created equal” was not repeated in the Constitution, but it provided the basis for American republican government, which the Constitution embodied and proposed to guarantee. Slavery made a mockery of any claims of equality.

For forty years Clay wrestled with these challenges. In the golden age of Congress, when the legislative branch retained the primacy intended for it by the founders, the silver-tongued Kentuckian had no equal for adroitness and accomplishment in the Capitol.

But he had some doughty rivals, two in particular. John Calhoun started out as a champion of federal authority, alongside Clay. But as Calhoun felt that authority weighing more and more heavily upon South Carolina, his home, he swung to the opposite pole, becoming the chief theorist of states’ rights.

Daniel Webster did the reverse. Amid the War of 1812, which sorely punished the commerce of New England, Webster proposed that if the pain became too great, the states of his region should reconsider their attachment to the Union. Yet before his career ended, the Massachusetts senator would be hailed as the Union’s most eloquent defender.

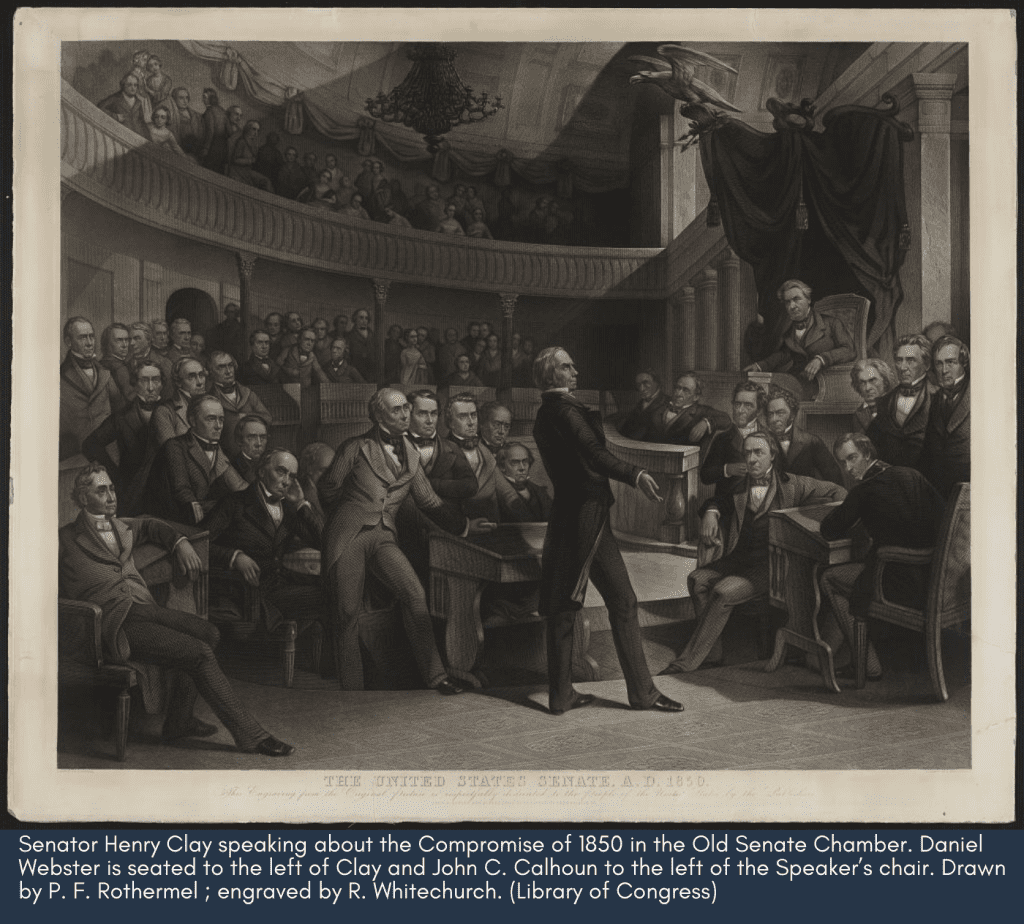

Clay, Calhoun, and Webster were the celebrities of their era. Politicians and civilians alike hung on their words. When one or another of the three was scheduled to speak in the Senate, Washington suspended business to listen. Clay’s defense of a protective tariff displayed a sophistication that wouldn’t be exceeded even two centuries later. Calhoun’s construction of state sovereignty persuaded eleven states to bolt the Union in the early 1860s. Webster’s rejoinder of national sovereignty was committed to memory by generations of schoolchildren.

They were called the “the Great Triumvirate” for the influence they wielded upon their fellow legislators. Clay earned a special sobriquet–”the Great Compromiser”–for his ability to pull the country back from the brink of disaster. Three times the Union approached the precipice: when Missouri’s admission compelled a reckoning over slavery in the western territories, when South Carolina vowed to secede if forced to pay a tariff it loathed, and when gold-rush California demanded a state government that forbade slavery.

In each case Clay crafted a compromise that preserved the Union. The last compromise, of 1850, was his masterwork, a fugue in eight parts that balanced the diverging interests of North and South. The effort exhausted Clay, already suffering from consumption, or tuberculosis. He died a short while later. Calhoun had died amid the debate over the compromise, of the same illness. Webster died soon after Clay, of complications from a carriage accident.

With their passing died the spirit of compromise that had enabled them to meet Franklin’s challenge. The spiritual sons of Calhoun made a fetish of states’ rights, especially the right to own slaves. When the Union-revering sons of Clay and Webster–most notably Abraham Lincoln–resisted the Calhounian interpretation of the Constitution, the country descended into civil war.

The war placed an outer bound on each of the twin problems Clay’s generation inherited from the founders, but it didn’t resolve either one. The Union victory effectively forbade secession, but it left lesser assertions of states’ rights tenable. The war-enabled Thirteenth Amendment proscribed slavery, but it said nothing about other inequalities that continued to vex republicanism.

A century and a half later, we still grapple with these problems. States argue with and sometimes sue the federal government over voting rights, abortion, health care, education, the environment and other issues. Inequalities of race, wealth, and opportunity sabotage our efforts to cultivate an inclusive democracy.

In the age of Henry Clay, the deepest divide in American political life was between sections: North and South, Today it is between political parties. But the spirit of compromise–of acknowledging the legitimacy of opposing views, and recognizing the need to incorporate them into law and policy–that allowed the Union to endure during Clay’s lifetime is no less necessary in our time.

Can we keep the republic? The task never ends.

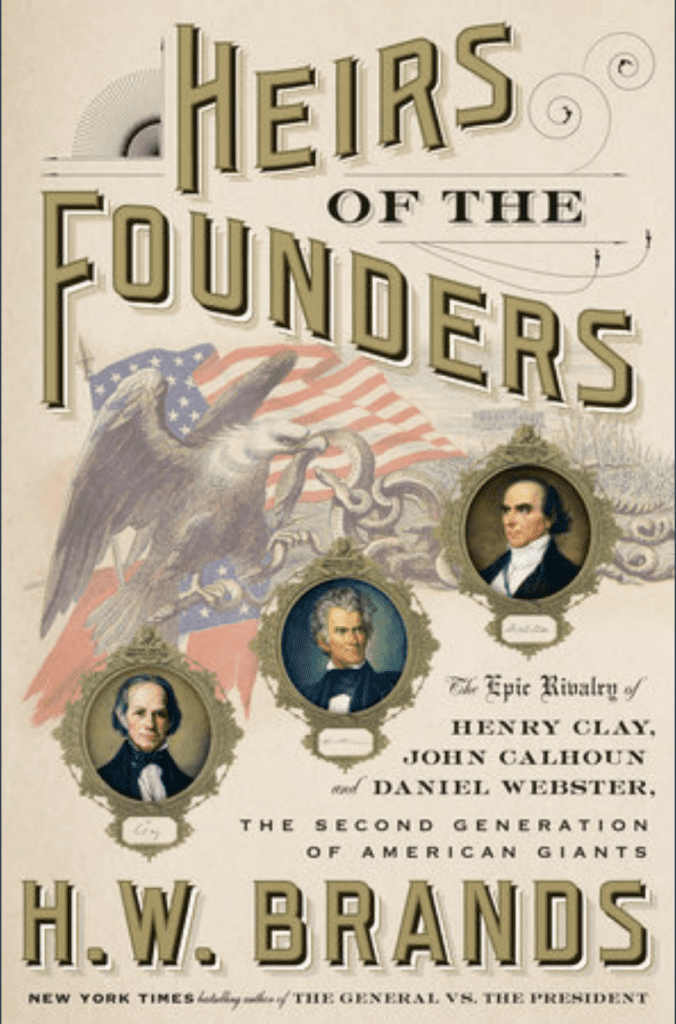

H. W. Brands, Heirs of the Founders: The Epic Rivalry of Henry Clay, John Calhoun and Daniel Webster, the Second Generation of American Giants (2018) tells the full story of the overlapping lives and careers of Clay, Calhoun and Webster.

For more on this period, take a look at:

H. W. Brands, Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times, (2006).

A biography of the general and president whose dying regret was that he hadn’t hanged Calhoun and shot Clay.

Merrill Peterson, The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, Calhoun, (1988).

It has for three decades been the standard account of the powerful trio. It is now superseded (Brands hopes) by Heirs of the Founders.

Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln, (2006). It casts the travails of the era in the context of the emergence of democracy as a transformative mode of politics, economics and culture.

Library of Congress guide to the Compromise of 1850