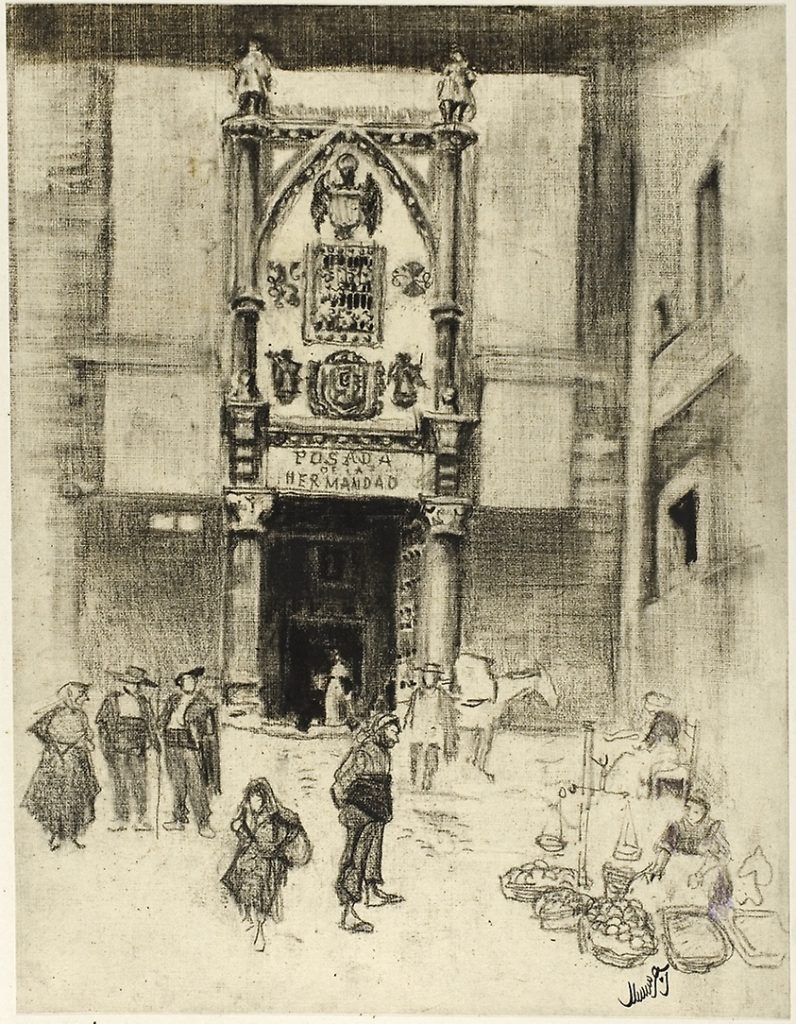

“Home of the Inquisition, Toledo” by Joseph Pennell 1903 (via Art Institute of Chicago)

On August 7, 1604, Dr. Martos de Bohorquez, prosecutor for the Mexican Inquisition, demanded that Justa Mendez face justice for scandalizing Mexico City society. In addition to seizure and arrest, Bohorquez stipulated that the captive be placed in a secret prison and punished as someone who had committed a serious crime. Authorities often issued warrants like this in matters of heresy. However, Mendez had not committed an offense against the Catholic faith. She had worn silks when prohibited from doing so. As a convicted heretic, Mendez faced a series of sumptuary regulations — laws that restricted people from wearing certain clothes or using particular items. Despite these prohibitions, witnesses reported that Mendez paraded about the city, carried on an ornate litter by African and indigenous servants, and dressed in finery. By exclusively addressing the unauthorized use of material objects, the case against Mendez represented an unusual divergence from typical inquisitorial efforts to root out heresy.

Sumptuary cases like the one conducted against Justa arose at the start of the seventeenth century. Beginning in March 1604, the Holy Tribunal of New Spain issued an edict banning current and former reconciliados — convicted heretics in the process of reintegrating into the Catholic Church – and their relatives from wearing or using certain goods. The regulation prohibited them from wearing gold, silk, other fine cloths, from carrying arms and from riding a horse. Denunciations began immediately and continued sporadically until March 11, 1617. Over that thirteen-year period, inquisitorial authorities received forty-six testimonies against twenty individuals and opened twelve formal trials.

Among the accusations, the case against Justa Mendez garnered attention as much for the young woman’s infamous reputation as a heretic as for her ostentatious fashion. First convicted for heresy in 1596, Justa had already acquired serious notoriety before her sumptuary trial. The daughter of two reconciled heretics, she also allegedly became the lover of Luis de Carvajal, one of the Inquisition’s most dangerous convicted heretics.

“Scene from an Inquisition” by Francisco Goya Lucientes, 18th century (via Wikipedia)

Testifiers depicted Justa as a woman unconcerned with her scandalous reputation. Instead, witnesses repeatedly commented on the audacity with which she dressed herself. Multiple people reported that Justa appeared regularly in expensive, imported fabrics and accessorized with silks, ribbons, and veils of delicate burato fabric. One account explicitly detailed the addition of a new velvet bodice. To complete her outfit, accusers reported that Justa frequently flaunted gold rings, necklaces of pearl and gold, and platform shoes forged of silver. Far from the apparel a religious penitent was expected to wear, Justa’s attire depicted her as a substantially wealthy female proud to show off imported fabrics, jewels, and precious metals.

Not only did Justa clothe herself in luxury, she also used objects otherwise reserved for high-ranking citizens. In particular, witnesses chronicled her use of a silla, a sedan-chair, to travel across the city. Covered in white weatherproof fabric with fine stringed fringe and curtains of taffeta, the pallet was reportedly carried atop the backs of either two black men or one African and one indigenous male. For added effect, Justa allegedly left the curtains open so as to see and be seen by everyone she passed. Perhaps more scandalous, Justa appeared to lend out the carrier out to friends. Denunciations noted that reconciliada, Constanca Rodriguez, had traveled from her store to the jail in the silla several times.

18th century French sedan-chair (via Wikimedia)

These accounts depicted a level of bravado in Justa’s actions not seen in other sumptuary trials. The punishment proposed by the prosecutor also reflected the severity of Justa’s actions in the minds of ecclesiastical authorities. Recommending immediate arrest and punishment, Bohorquez condemned the “perpetrator of such a grave crime” and begged the authorities to detain her in a secret jail as soon as possible.

Although the scandal generated by Justa’s transgressions gathered attention in its own right, trial testimony also singled out another agitator, Anna Vaez. Officials originally reprimanded her for wearing a black Chinese silk dress with a burato veil. However, Anna countered the accusations by questioning “If whichever black” could wear it “why can’t she?” Accounts only addressed the interaction in passing. However, such reports revealed a key insight into the complex tensions between persecuted religious outsiders, like Justa and Anna, and marginalized socio-racial communities.

Unlike those of mixed ethnic descent, heretics did not occupy a designated space within the racial hierarchy of colonial Mexico. Nonetheless, the Spanish legal system imposed almost identical sumptuary regulations upon reconciled Jews and non-Spanish groups. Since 1571, royal law had prohibited black and mulatas – women of African and Spanish descent — from wearing silk, burato veils, pearls, or gold. By 1612, authorities in New Spain extended such restrictions to all black and mulato populations, free and enslaved. Likewise, the 1604 inquisitorial edict restrained reconciled heretics from wearing silk, fine cloths, and gold. Such bans, contemporaneous of each other, effectively categorized Africans, mulatos, and former heretics into identical juridical classifications.

In light of this legislation, Justa’s employment of Africans and natives thus acquired new meaning. Justa asserted her superiority by literally sitting on top of her non-Spanish carriers. Furthermore, she established a highly visual – and very public – power differential. Despite their different methods, both Justa and Anna directly challenged the similar categorizations of African, indigenous, and convicted Jews. Their defiant actions suggested that they did not accept the legal classifications that subjected them to equal discriminations as non-Spanish groups. Instead, the two women distinctly rejected any sense of equality between themselves and African-based castes. For Justa and Anna, the use of clothing and items reserved for the elite served to demonstrate their superiority to casta groups.

While reports against the two women demonstrated underlying socio-racial tensions, the majority of the case file emphasized a more obvious contradiction: that between the luxuriousness of the clothing and the ostracized status of the wearer. Witnesses that registered objections to the infractions of heretics like Justa fixated on the quality of their clothing relative to their notorious standing as active penitents. The public noticed clear attempts to draw attention, such as the open silla curtains, and condemned such displays to sway prosecutors towards harsh punishment. Colonial inhabitants clearly perceived the use of prohibited objects by certain individuals as potentially dangerous. Ultimately, the case against Justa Mendez represents just one example of the broader attempt to categorize and control colonial society through appearance.

Justa’s case is recorded in the Archivo General de la Nación de Mexico, Ramo de Inquisición, volume 1495, expediente 2.

Additional sources for this article are:

Eva Alexandra Uchmany, La Vida Entre El Judaísmo y El Cristianismo (México: Archivo General de la Nación, 1994)

The Grandeur of Viceregal Mexico: Treasures from the Museo Franz Mayer, ed. Héctor Rivero Borrell M., Gustavo Curiel, Antonio Rubial García, Juana Gutiérrez Haces, and David B. Warren (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002)

Other articles you might like:

The King’s Living Image: Politics of Viceregal Politics in Colonial Mexico

Of Merchants and Nature: Colonial Latin America Through Objects

Other articles by Haley Schroer:

Infrastructures of Race: Concentration and Biopolitics in Colonial Mexico

Antonio de Ulloa’s Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional