“Let this really be brief!” was the first thought that crossed my mind as I read the title of Patu and Schrupp’s book. It was listed on the syllabus for a course on Gender and Decolonization and after some heavy reading on decolonization, I was less than enthusiastic about reading this book. I had not heard of it before and let’s be honest, we have come across “Brief Histories…” on foundational concepts (nationalism, existentialism, socialism or any -ism you would like to add here) that promise brevity but turn out to be 300+ pages of dense, jargon-filled exercises in theoretical name-dropping.

In retrospect this book signaled its difference right in its cover design. Instead of monochromatic colour schemes, sober font styles, and a black-and-white picture of a dead white lady proclaiming its seriousness, we see a quirky, multi-hued, animated cover with illustrations of key feminists. At this point, I thought the cover was off-beat but was still not prepared for the content, so you can imagine my shock, relief, and utter sense of joy when I found out the whole book was ILLUSTRATED! Yes, a comic book for feminism! Fans of Marjane Satrapi’s Persopolis series will discover parallels in this book that skillfully combines graphics, narrative, humor, and history to provide a powerful account of women’s lives, struggles, and victories.

Patu and Schrupp rescue feminist scholarship from academic confines and present it to a new generation of general readership in a way that is most palatable to them. The ascendance of Instagram, Snapchat, Anime and Marvel comics have elevated the status of images in our society. Millennials consume information as well as tell their stories increasingly through digital images or emojis. Mainstream sitcoms such as Blackish have tapped into this phenomenon and use graphics intermittently to present the dark side of Black history succinctly and with humor so that all Americans can comprehend the gravity of African-American experiences.

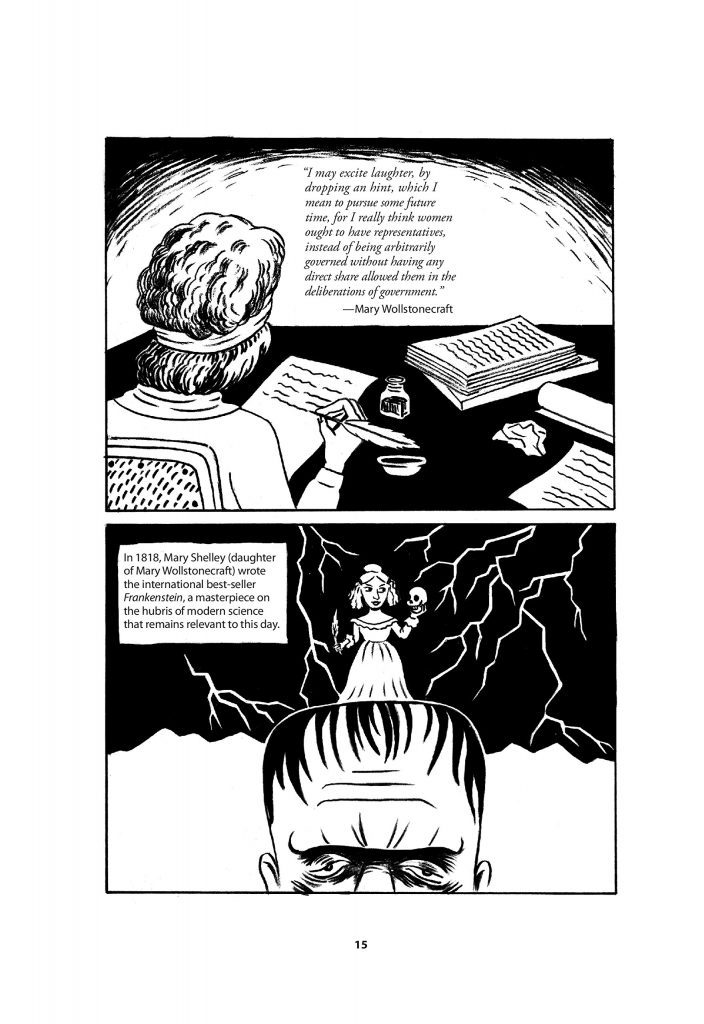

A page from A Brief History of Feminism (via Amazon)

A Short History of Feminism acknowledges these new trends and ushers feminism into contemporary focus by using graphics to treat feminist history not as a relic of the past trapped in a sea of words and theories that has no place in our present. Graphics woven masterfully with humor signal the contemporary relevance of this topic. This combination strikes the right balance between levity and gravitas and emerges as a medium with powerful immediacy. The book’s pictorial stories thus draw us into a continuum that connects our collective past, present, and future. Female characters are not busy enacting ‘history’ but occasionally look straight to the reader and address them as in the case of French philosopher, Marie de Guornay (1565-1645). These female voices are direct, contemplative and sometimes funny as they mouth our own contemporary concerns about equal pay or work-life balance. These women acknowledge us, talk to us and remind us that the struggle is not over.

One highlight of this book is that we really do get a brief run through of feminists from ancient to modern times. This book is also a great quick reference to various female figures, little known facts about them, and the social situations that gave birth to their individual struggles. From Mary Magdalene to Sappho, Sojourner Truth to Gloria Steinem, the book surfs deftly through all the waves of feminism. The authors cover topics ranging from workplace to marriage rights, suffrage to political participation to provide a broad introduction to all the areas in which women fought hard to win rights.

Flora Tristan’s (1803-1844) story struck me as particularly fascinating because the French-Peruvian fought not only for female rights but also rallied against slavery and class exploitation. She composed an important socialist treatise called The Worker’s Union in 1843, a full five years before Marx and Engels published The Communist Manifesto where she displayed crucial links between oppression of women and the proletariat. Yet, she is a marginal figure, which Patu and Schrupp demonstrate poignantly by showing Marx shushing Engels when the latter mentions Tristan’s name. Das Patriarchy, anyone?

Another highlight is that the authors do not assume universal sisterhood when it comes to feminist concerns. Feminism and its various iterations are constantly evoked to remind us that this concept is not ubiquitous, monolithic, and bourgeois but something that is in constant flux and assumes various forms. We get the varying concerns of proletariat and upper-class women as well as Black slave-women and socialist women. The display of a plurality of voices appears to be the main agenda of the book but despite the emergence of a multitude of voices, the book is predominantly the history of white, Christian, Western European and American feminists. It is not a history of feminism but western feminism, which frankly, as a South Asian woman left me feeling marginalized. One the one hand, western women have been an instrumental force in ushering global rights for women but their stories are not the only ones worth telling. If the authors are interested in presenting a wide range of stories, women from Asia, Africa, and Latin America have their own unique struggles and victories to recount Modern feminists such as Gayatri Spivak, Maria Lugones, Denise Noble, and Madina Tlostanova provide great insights into non-white, non-western women’s movements and their works deserve an illustrated book so that women from Central Asia to the Caribbean can see themselves reflected in a truly global and plural feminist movement.

A Short History of Feminism is a compelling, funny, and thoroughly enjoyable book. It contains universal appeal that demystifies western feminism and can easily be enjoyed as leisure reading or an introductory book in a college freshman class. My only appeal, and I believe a lot of readers would agree, is that may we have second part to this collection please!