Centuries before contemporary debates about anthropogenic climate change took shape, early British settlers to New England and Nova Scotia believed that they could “improve” the climate of these otherwise inhospitable regions by placing the land under cultivation. In A Temperate Empire, Anya Zilberstein draws from a rich primary source base to analyze how these early ideas of anthropogenic climate change developed in relation to British colonialism and Anglo-American understandings of race. Decentralized networks of genteel amateur scientists spread throughout the British Empire and the Atlantic World exchanged weather reports, observations, plant and mineral specimens, and technical instruments with the goal of “improving” agriculture and local environments. By their own estimation, the climate had warmed significantly over the course of the 17th and 18th Centuries, even though, as Zilberstein points out, their observations coincided with some of the coldest decades of the Little Ice Age.

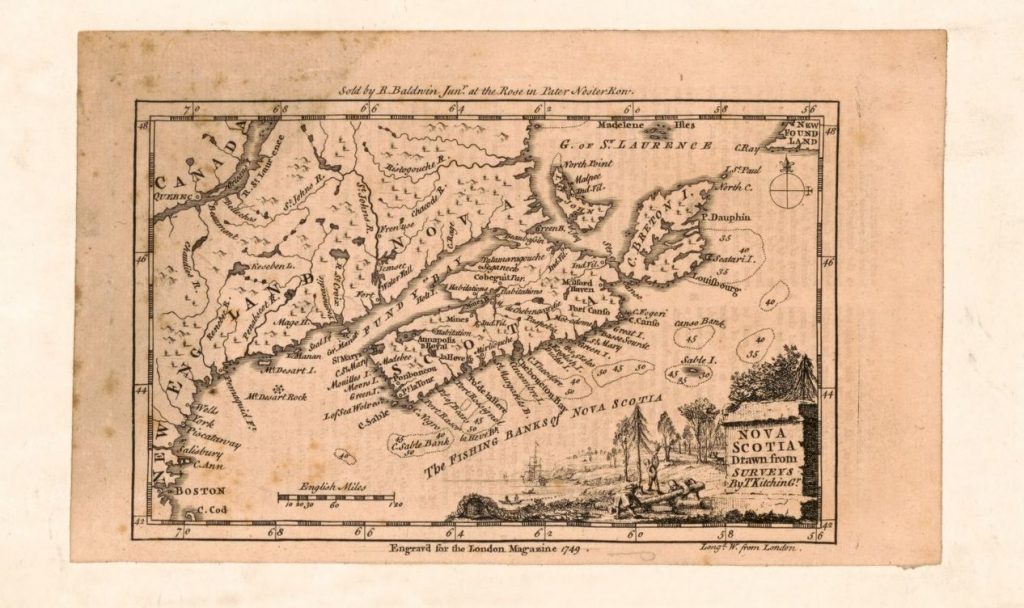

By examining the debates surrounding the nature of the North American climate, Zilberstein shows how exposure to the new environments of northeastern North America challenged prevailing beliefs about the connection between latitude and climate. Roman and Greek geographers assumed that bands of tropical, temperate, and polar climates wrapped around the globe, an idea that Europeans carried with them to the “New World.” Early explorers and settlers anticipated that New England would have had a climate like Northern France, and that Nova Scotia would resemble Scotland due to their similar latitudes. In reality, however, the regional climates defied the expectations of the colonizers, proving to be dominated by brief yet hot summers, and frigid, long winters. Regardless of these significant challenges, local landowners, agriculturalists, and natural historians aimed to reinforce the idea that the two areas possessed healthy, temperate climates in order to help attract settlers.

Writings by prospective settlers, farmers, and foreign travelers who believed that Europeans ought to settle in “temperate” climates help Zilberstein show how early colonists encountered and understood the climates of New England and Nova Scotia. The author shows a progression from early writings on climate that emphasized latitude, to an understanding of climate than emphasized cultivation and agricultural improvement as a crucial determining factor. Referring to correspondence and the records of agricultural promotion societies, much of which had previously received little to no attention from historians, shows the circulation of knowledge through networks of scholarly gentry, and how the knowledge moving through these networks began to disrupt previous understandings of the climate. The gentleman scientists of colonial New England sought to “acclimatize” the landscape by putting it under cultivation, organizing themselves into learned societies and exchanging scientific information and tools as a form of patronage and “cosmopolitan sociability” (pp. 54). Here, Zilberstein’s attention to the transatlantic nature of knowledge circulation networks and how they persisted from colonial to post-colonial times in the United States stands out as an especially admirable historical contribution.

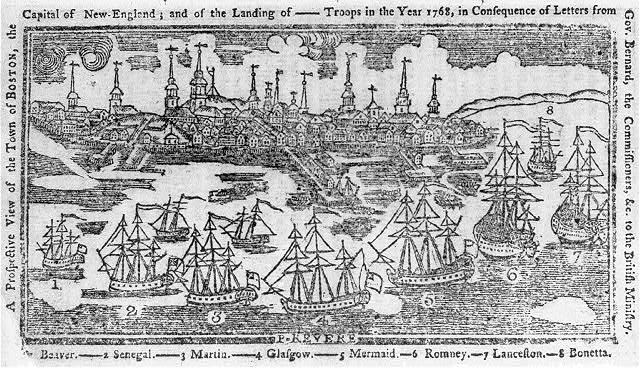

After addressing knowledge circulation networks in New England, the book turns its attention to the colonial government of Nova Scotia and its efforts to attract settlers to the colony despite its frigid, often inhospitable climate. Zilberstein notes that a previous colonial experiment in Panama led Governor Samuel Vetch to believe that settlers from cooler temperate areas like Scotland or Northern Europe would be ideal for the region, but failed to attract sustained interest. The connections between ideas of race/ethnicity and climate are further examined by the author when she examines the attempted relocation and resettlement of 568 Jamaican maroons to Nova Scotia in 1796. Local elites and international abolitionists lambasted this decision, since mainstream thinking about race contended that Africans could not adapt to a frigid climate. Her use of this case study again allows the author to transcend traditional historiographical boundaries between nation-states and between different parts of the British Empire, placing extremely local phenomena in dialogue with global scientific discourses.

The book ends without a separate conclusion, a decision which invites the reader to return to and reread the introduction, or otherwise to reflect on the book’s core themes and integrate the chapters on their own. While this may be a surprising decision for some, at the same time, it could be seen as encouraging conversation and discussion when the book is assigned for a class. Some may wish that the author had devoted more time to the role of the indigenous people in producing knowledge about the local climates. Although Zilberstein acknowledges the presence of Native Americans, her book tends to focus explicitly on the elite production and circulation of knowledge. Nonetheless, the book offers a thought-provoking analysis of how ideas of climate and anthropogenic climate change developed along colonial frontiers, providing a valuable look into an otherwise understudied historical phenomenon. It has the potential to be of broad interest not only to academics but also to members of the general public interested in learning more about how our contemporary ideas of climate have developed.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.