By Raymond Hyser

This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

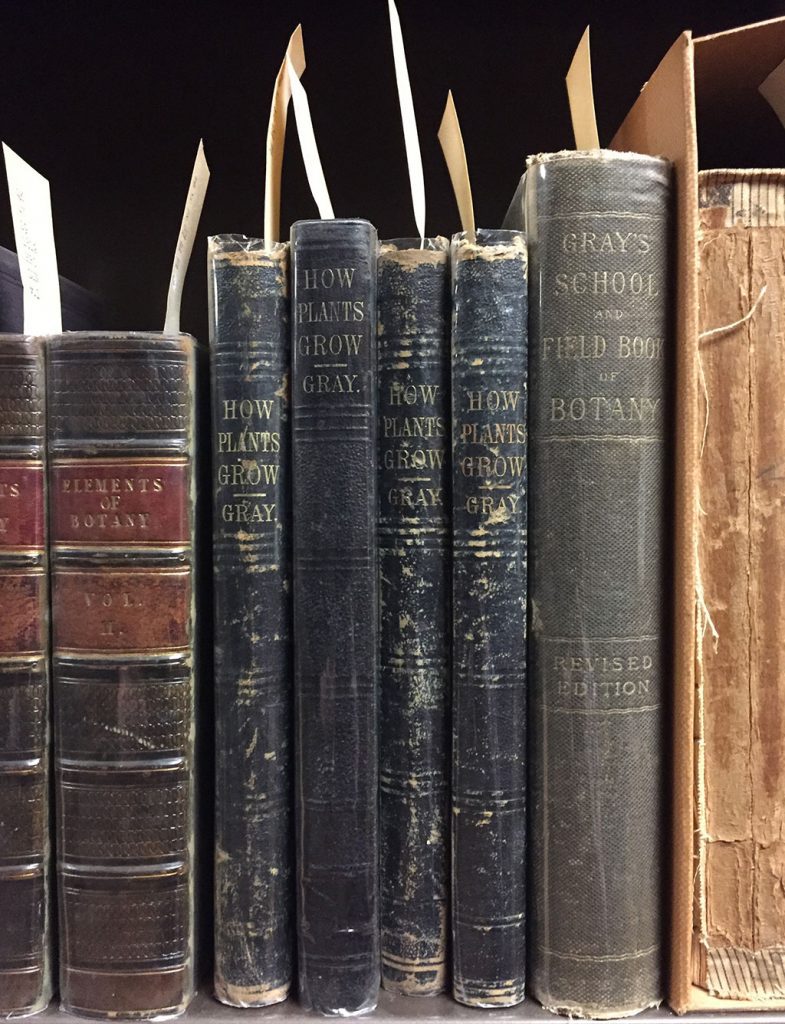

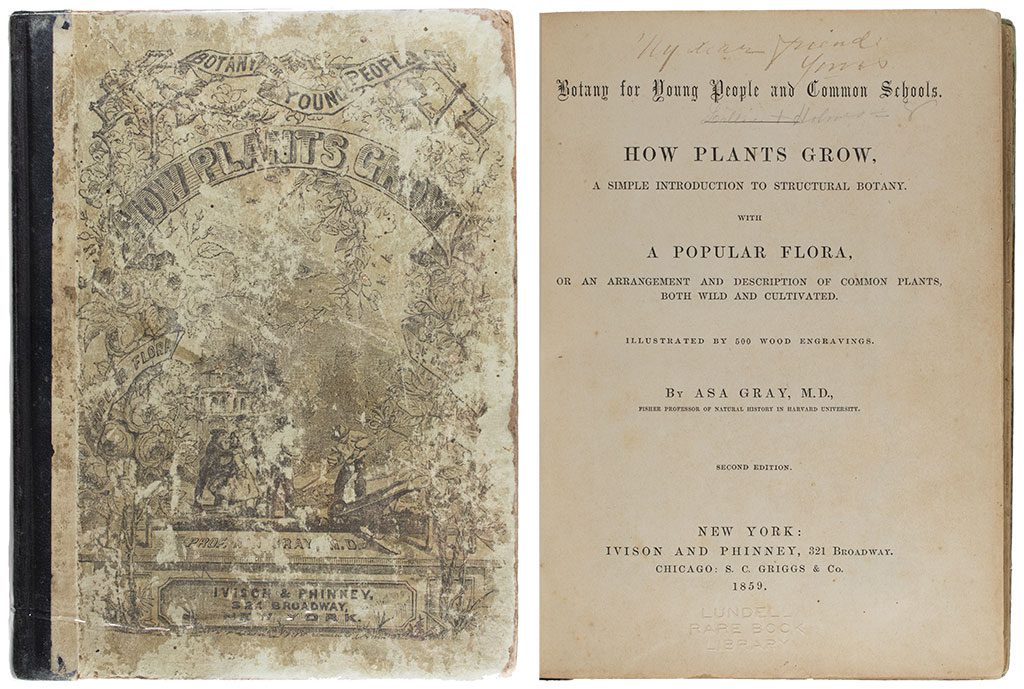

Located on a secure floor in the Ransom Center’s stacks and nestled on a shelf between several other copies of the same title, sits an unassuming blue book. Printed along its spine in golden letters is a rather capacious title, How Plants Grow, followed by the name of its author, “Gray.” This somewhat ordinary book is part of the large library of the American botanist Cyrus Longworth Lundell. It includes some six thousand books, manuscripts, and journals, all of which deal variably with cultivation, gardening, plant taxonomy, and systematic botany. Many volumes came into Lundell’s possession from the library of Oakes Ames (1874-1950), another American botanist who specialized in orchids. These provide the collection with an impressive assortment of rare botanical books that spans the sixteenth to the twentieth century. In particular, the Lundell stacks boast important works from the likes of Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778) and Charles Darwin (1809-1882). While not written by the famed British naturalist, How Plants Grow was penned by one of Darwin’s longest running correspondents: Asa Gray.

Born in New York state in 1810, Gray is one of the most famous and influential American botanists of the nineteenth century. Trained as a medical doctor, he received an M.D. in 1831 but quickly deserted the practice of medicine in 1832 to pursue his true passion: botany. He held a number of teaching and library positions over the next decade, until in 1842 he accepted the Fisher Professorship of Natural History at Harvard University, where he would stay for the remainder of his working life. From his well-funded position at Harvard, Gray developed a reputation as a leading authority of botanical taxonomy in the United States: he wrote extensively on the flora of North America. Gray’s writings on the geographical distribution of plants so impressed Charles Darwin that he shared his secret hypothesis of the origin of species with the Harvard botanist prior to publishing his now famous work on the subject in 1859. Despite being a devout Presbyterian, Gray put great stock in Darwin’s theory and became one of Darwin’s leading supporters in America.[1]

While most famous for his taxonomical work, particularly his Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States (the Lundell Collection has several editions of this book), Gray also played a major role in the country’s scientific education. Surprisingly this was not as a teacher, however, as he was known to have been a poor lecturer. Rather, his educational impact came from a number of his influential textbooks, which shaped botanical education in the United States from the 1840s until well into the twentieth century. First published in 1858, How Plants Grow was one of these.[2]

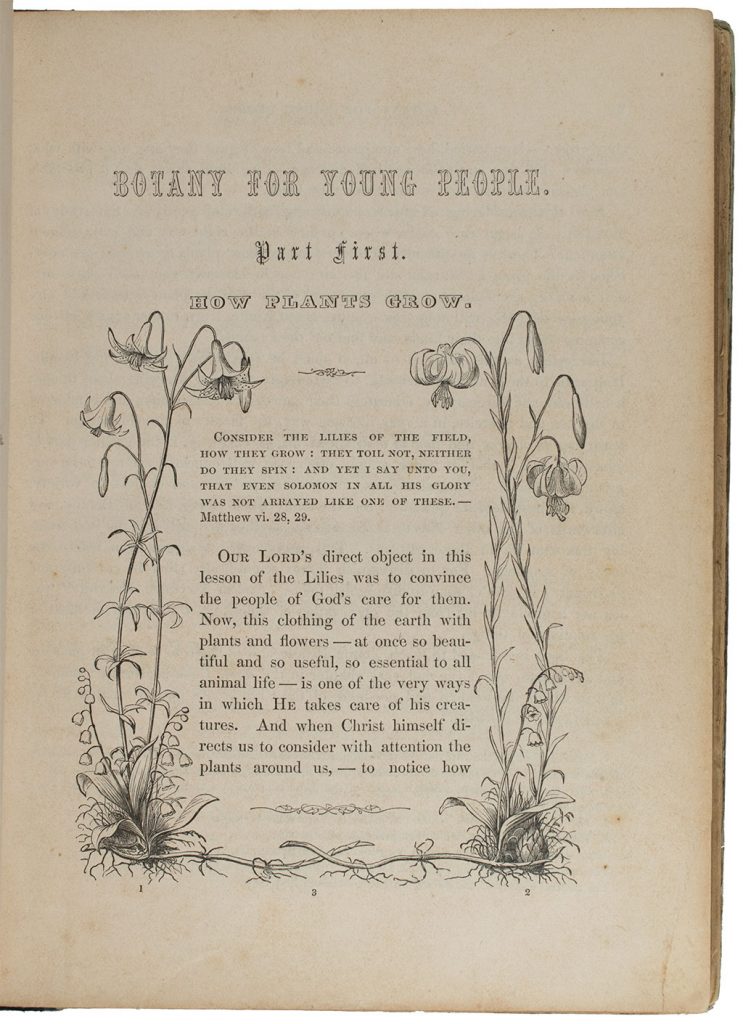

In true nineteenth-century fashion, Gray’s book boasts a lengthy title that tells any potential reader exactly what content they will find sandwiched between the book’s covers. The full title is Botany for Young People and Common Schools. How Plants Grow, A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany. With A Popular Flora, or an Arrangement and Description of Common Plants, both Wild and Cultivated. The first part of the title highlights the book’s intended audience, “young people and common schools.” At the behest of the publishers at Ivison and Phinney, Gray sought to write a book that was not intended to be used by botanical experts nor by the students in his Harvard classroom. Instead, he meant to write an accessible introduction to the study of botany that could be used in high school classrooms and easily read by non-experts. In particular, Gray wanted to share his botanical expertise with “Young People,” as it would appeal to their “natural curiosity” and “lively desire of knowing about things.”[3]

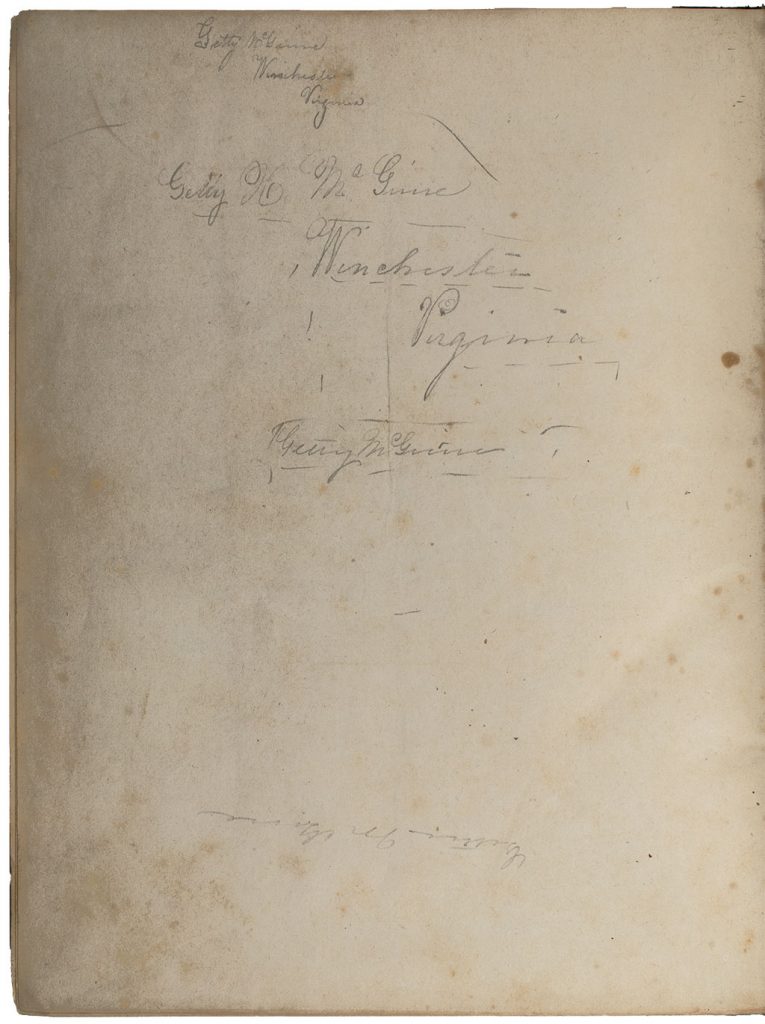

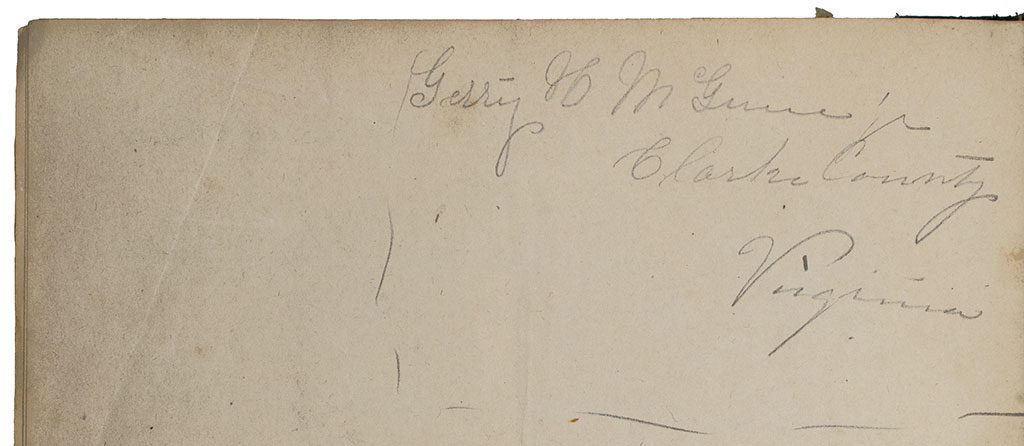

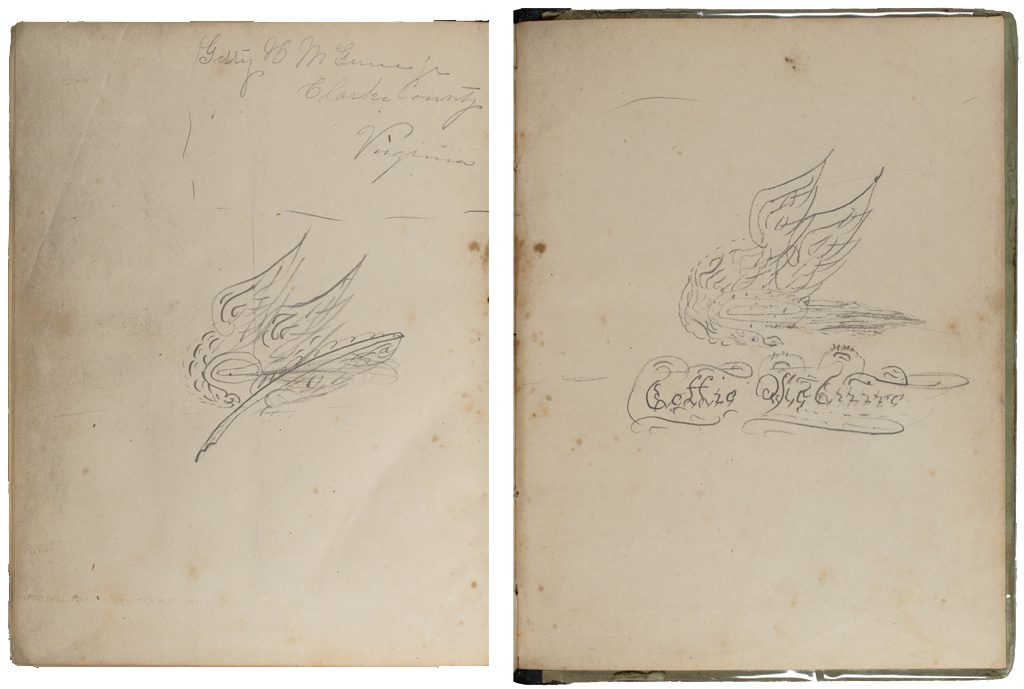

One such young person was a “Getty H. McGuire,” who has inscribed the Lundell volume numerous times. This may be the Margaretta Holmes McGuire—known by her friends and family simply as “Getty” or “Gettie”—who was born in 1833 in Frederick County, Virginia. She was the daughter of Ann Eliza Moss McGuire and Dr. Hugh McGuire.[4] Dr. McGuire was a well-known surgeon and with a strong interest in science, animals, and medicine.[5] His professional and intellectual curiosities may have led him to purchase How Plants Grow for Getty or, very possibly, Getty may have requested or purchased the book herself. Regardless of how it came into her possession, Getty made it quite clear that this particular copy of How Plants Grow belonged to her. Sometimes in hastily scrawled, almost illegible script and sometimes in neat, underlined cursive, her signature appears in a handful of forms and styles across the endpapers of the book. Given both the prevalence and different variations of her signature, it appears that she used the book’s blank pages to practice her signature in addition to claiming ownership of the book. Occasionally she included “Winchester, Virginia” after her signature, which helpfully identifies the place where she and the rest of the McGuire family resided in the late nineteenth century.

That said, “Clarke County, Virginia” also follows one of Getty’s signatures. Given that Winchester is located in Frederick County, the listing of nearby Clarke County may indicate that the book’s owner is actually a different woman of the same name. Confusingly, another Margaretta Holmes McGuire, who lived contemporaneously to Getty, resided and was ultimately buried in Berryville, a town just to the east of Winchester in Clarke County. Born in 1844, the Margaretta from Berryville was the daughter of Nancy Boyd Moss McGuire and William David McGuire.[6] Coincidentally, her father was also a doctor who lived in Winchester, Virginia.[7] It does not appear that the other Getty McGuire ever lived in Clarke County, tipping the balance in favor of the Margaretta H. McGuire who lived and died in Berryville, VA.

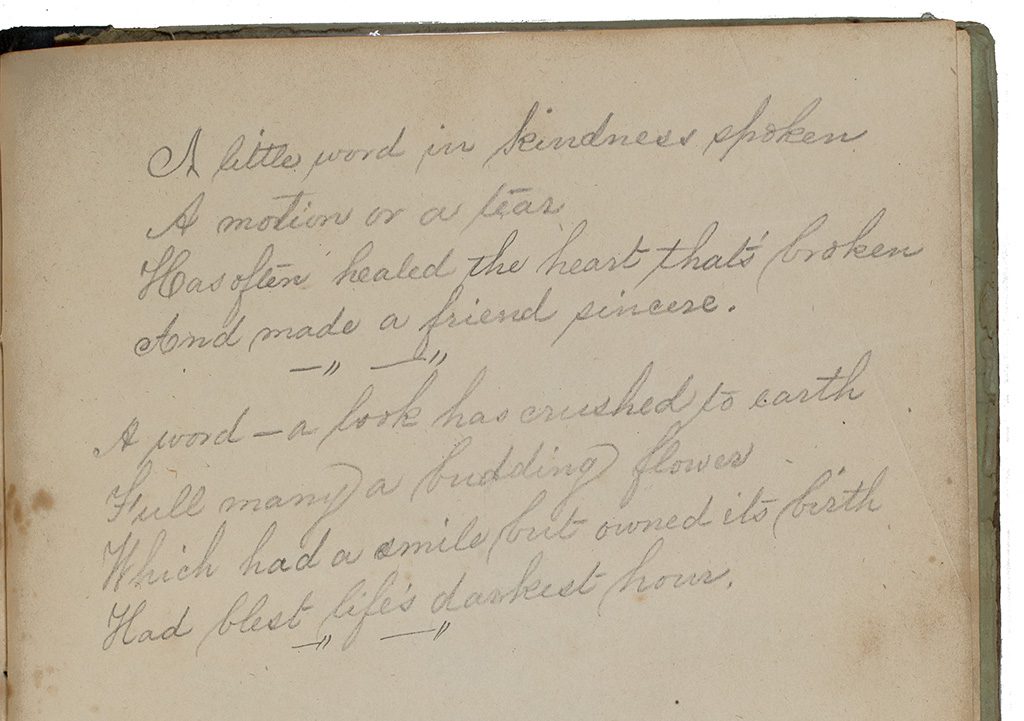

Signatures are not the only inscriptions Getty made in her copy of How Plants Grow. Occupying about half a page at the end of the book, Getty reveals an interest in poetry by copying out two stanzas from an often-printed contemporary poem. They follow a catchy a-b-a-b rhyme scheme:

A little word in kindness spoken

A motion or a tear

Has often healed the heart that’s broken

And made a friend sincere.

—“ —“

A word—a look has crushed to earth

Full many a budding flower

Which had a smile but owned its birth

Had blest life’s darkest hour.

—“ —”

While only eight lines long, the verse provides a glimpse at Getty’s literary side, indicating familiarity with the conventions and imagery of contemporary poetry. The lines, however, do not draw on the abundance of botanical imagery found in the textbook—only a single one refers to a “budding flower.” Her inspiration seems to have been drawn from elsewhere, the page at the end of Gray’s book simply used as a blank slate to record the poem for posterity.

In another show of creativity, Getty added her drawings alongside How Plants Grow’s 500 printed illustrations of flora and their parts. Her artwork, however, demonstrates an interest in fauna. On one of the book’s endpapers rests a seemingly magical creature with large, unfurling wings (perhaps a dragon or, less mystically, a swan?) that curls around itself next to a large, feather quill. On the adjacent page, a more detailed version of the same creature crouches above “Gettie McGuire,” written in an ornate script. These images are perhaps more apt to be found in a fairytale than a book about botany; they are reminiscent of the doodles found scrawled in the margins of many modern-day textbooks by bored students. As these drawings, along with her poem, provide a small window into the imaginative mind of the book’s initial owner, Margaretta “Getty” McGuire, they also remind us that books often serve their readers—their users—in ways authors and publishers never intended. They also remind that the lives of ordinary people can show up in unexpected collections. With this volume, Getty McGuire has earned herself a place in the history of science.

Raymond Hyser is the Digital Humanities Developer for Not Even Past and a PhD student in History at the University of Texas at Austin. He received his MA in the Social Sciences from the University of Chicago and his BA in History and Art History from the University of Virginia. He focuses on environmental history and the history of science within trans-imperial spaces during the nineteenth century with a special interest in world history and digital humanities.

[1] “Gray, Asa,” in Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 5. (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2008), 511-14.

[2]A. Hunter Dupree, Asa Gray, American Botanist, Friend of Darwin (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, 1988), 125-131.

[3] Asa Gray, Botany for Young People and Common Schools. How Plants Grow, A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany. With A Popular Flora, or an Arrangement and Description of Common Plants, both Wild and Cultivated (New York, NY: American Book Company, 1858), 2.

[4]Sarah Kay Bierle. “Biographical Information,” Gazette665, accessed November 15, 2020, https://gazette665.com/research/mcguire-family-research/the-mcguire-family/ and Sarah Kay Bierle, “The Winchester Photograph: Portrait of A General’s Character,” last modified November 11, 2015, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2015/11/11/the-winchester-photograph-portrait-of-a-generals-character/.

[5] Bierle. “Biographical Information,” https://gazette665.com/research/mcguire-family-research/the-mcguire-family/ .

[6] “Margaretta Holmes McGuire White,” Find A Grave, accessed December 27, 2020, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/47021092/margaretta-holmes-white.

[7] “William David McGuire (1810-1877), WikiTree, accessed December 27, 2020, https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/McGuire-3278.