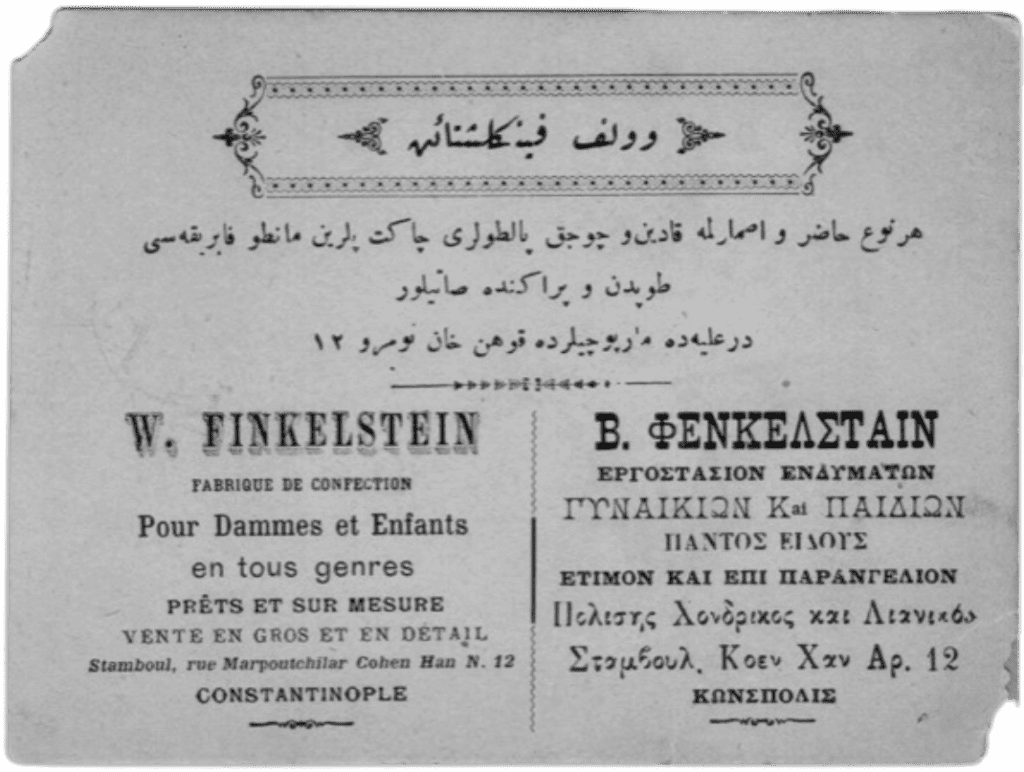

In 1884, a twelve-year old boy got into a fight with his parents. Pious Ashkenazi Jews from the manufacturing city of Lodz in Poland, they were traveling by ship to make a new home in the Holy Land. Once in Constantinople, unbeknownst to his parents, Wolf Finkelstein stepped off the ship and into a rowboat. He then delivered an ultimatum to his mother and father: either they would allow him to remain in the city or he would throw himself into the Bosporus. His (presumably reluctant) parents left the boy in Constantinople to fend for himself, which he did. Within a few days, he found a job as an apprentice to a tailor; within a few years, at the age of eighteen, he started his own tailoring business, then, over the next few years, went bankrupt, started more businesses, married, and had four daughters.

Who were the Jews of the Ottoman Empire? The prototypical Ottoman Jews were those Ladino-speaking residents of the Greek and Anatolian cities of Salonica, Smyrna, and Constantinople (now Thessaloniki, Izmir and Istanbul) bordering the Aegean, Black and Mediterranean Seas. They were the descendants of the Spanish and Portuguese refugees who had fled the Inquisition and the mass expulsions of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Many of them carried Spanish surnames such as Cuenca, Perez and Tarragano.

But the Ottoman Empire was also a cosmopolitan empire; and there were also Berber-speaking Jews in North Africa, a few tens of thousands in the Palestinian holy cities of Jerusalem and Safed, merchants in the port cities of Beirut and Benghazi, and the enormous, Arabic-speaking community that, at 53,000, constituted one-third of the population of Baghdad.

After almost a century of near-exclusive focus on the culturally and intellectually fertile world of Yiddish- (and French, German, Russian, and Polish-) speaking Ashkenazi Jews dwelling in the vast region between Eastern France and Western Russia, the last few decades have witnessed an explosion in the study of Jews from predominantly Muslim lands. Collapsed under the name of “Sephardi-Mizrahi” studies (Sephardi, meaning Spanish, Mizrahi, meaning “from the East”) this includes Jews from a 3500-mile expanse stretching from Morocco to Iran.

Indeed, the steady increase in numbers at the Sephardi-Mizrahi Caucus lunch at the annual conference of the Association for Jewish Studies testifies to the fact that Sephardi-Mizrahi studies has gone from being the neglected stepchild to the cool new kid of Jewish studies. And with good reason, as this exciting scholarship has opened not only new cultural understandings of Jews but has deep implications for theorizing the complex relationships between Jews and Islamic legal frameworks, European colonialisms, religious minorities’ belonging to the nation-state, and trade, family and educational networks.

But the construction of this field—which deserves all the attention it receives—has so far paid scant attention to the way that Ashkenazi and Sephardi fates overlapped and were intertwined. One group that is little-mentioned in the history of Ottoman Jews are the Ashkenazim who were drawn to and settled in the Ottoman Empire—drawn to it for economic opportunity but also to escape the pervasive discrimination and threat of violence that were particularly present in the late-nineteenth-century Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. In fact, these reasons were not so different from those for which their cousins migrated to New York City around the same time.

The presence of these Ashkenazi Jews is not new information, in fact the Galata neighborhood in Constantinople had at least three Ashkenazi synagogues. French Ashkenazi Jews from Alsace-Lorraine with names like Brasseur emigrated to Beirut; Russian Ashkenazim with names like Hochberg created new lives in settlements like Ness Ziona in Palestine.

And perhaps none of this should be surprising or even an issue. After all, to a Yiddish-speaking Jew from Ukraine or Hungary, Constantinople was no farther geographically, culturally and linguistically than it would have been to the Arabic-speaking Jew in Baghdad or Aleppo. The categories of Ashkenazi and Sephardi mattered in some ways, but almost certainly not in the way that the organization of luncheons at the AJS conference might indicate.

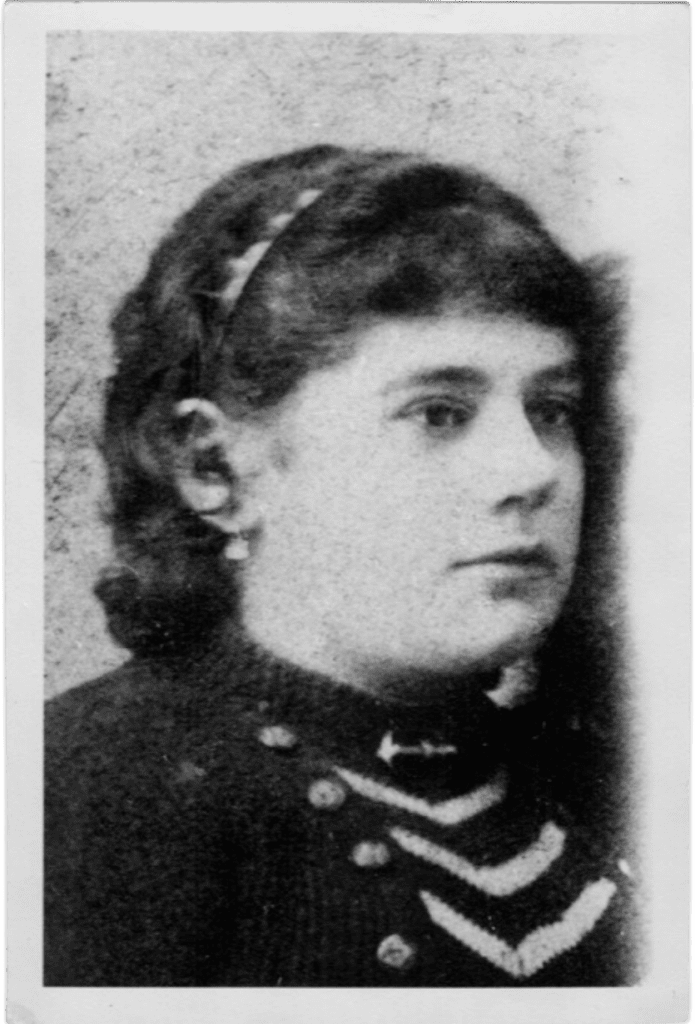

By the time Serafina Hirsch arrived in Constantinople in her early twenties, she had already crossed so many boundaries armed with her prodigious ability to learn languages (she knew fourteen) and adapt to new settings, that Constantinople was, in all likelihood, just one more strange and different place. Semi-orphaned at a young age, she moved around Central and Southern Europe, from the home of one older sibling to another. At a young age, she was working as an impresario for a small Jewish orchestra, traveling and booking venues around the Balkans. She spent three years in Budapest learning French and made her way to Constantinople sometime around 1900, where she worked for a time as the French teacher to the daughters of a wealthy Turkish general.

It was during this time that Serafina met Wolf. Precisely how, we don’t know, but perhaps it was through one of the Ashkenazi synagogue communities in Galata, or else through mutual friends. Perhaps they met in a café or in any number of one of the venues young people socialize in exciting, cosmopolitan cities, in the same way that their daughter would meet her future husband in late 1920s Berlin.

Either way, they married in 1901, and the following year, Serafina gave birth to their first child, Edith, in the garden of a house overlooking the sea in Salonica (in the garden, as she was carried out of the house during the birth in the middle of an earthquake). The couple’s linguistic flexibility was such that these two Ashkenazi Jews not only hired a Greek servant but spoke Greek to one another, and Greek was Edith’s first language. Their second daughter was named Renée. Wolf’s tailoring business foundered, and the family left their Constantinople neighborhood of Pera and moved to Smyrna. Perhaps Wolf’s lack of success with his small businesses presaged the final collapse of an empire that was, unbeknownst to him, in severe decline even when he arrived.

And then, twenty-two years after Wolf had fought with his parents, Serafina and he moved again, taking the two small girls to another capital of another empire—France. The girls, along with the two sisters who were born there, would attend French schools, absorb French culture, and hereafter identify themselves as French even though they never did obtain French citizenship. Edith, in particular, loved l’école and spent hours copying scenes from French history into notebooks. The girls spent summers living with French peasants in Normandy and Auvergne, or with their parents at the sea near Calais.

But the Ottoman Empire continued to mold their experiences. Edith’s dark hair and olive skin drew attention in the family’s Paris neighborhood of Montmartre, and she was called “Turquoise” (Turk) and “Youpine” (dirty Jew) as both racial and antisemitic slurs. The early twentieth-century French version of Mean Girls told her to go back to her country and eat macaroni. (“Why macaroni?” Edith wondered, “I’m not Italian.”) More ominously, as a Turkish citizen, Wolf was imprisoned in a concentration camp for several months at the beginning of World War One and after his release was forced to relocate to neutral Spain. He left Serafina to manage the family’s tailor shop amid unfriendly neighbors and to send the four terrified young girls to live in the French countryside away from the German shelling of Paris, supervised by a twelve-year-old Edith.

As soon as World War One ended, Serafina and the girls joined Wolf in the “capital” (New York) of yet another empire (the United States). From this point forward, the Finkelsteins’ lives were defined economically by America and culturally and linguistically by France and Europe. Just as it did for most of the Ashkenazi Jews who had at some point or another, had made lives and homes within the Ottoman Empire, the empire ceased to have not only political and legal, but cultural and economic meaning for them. Those Jews who stayed did not fare well, and tens of thousands within its former borders were subsequently murdered in the Holocaust. Many other former Ottoman Jews from communities in Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey emigrated, and in so doing, re-oriented themselves to new cultures and economies in the United States, Israel, France, and Latin America.

Wolf and Serafina were each drawn to the Ottoman Empire by its vitality and the opportunities that its cities seemed to promise. In this, they were like thousands of Ashkenazi, Yiddish-speaking Jews who were pulled into its orbit but who left when the actual opportunities could not support a growing young family. How their stay there would end was not something that could have been known to them when Serafina gave birth to Edith overlooking the sea in Salonica, or when two young Ashkenazi Jews met in the bustling and cosmopolitan capital of a declining but still-vital empire, or when a twelve-year-old boy made the decision to thwart the will of his parents and break from their destinies by stepping into a rowboat. Either way, the Ottoman Empire, by pulling them in and pushing them out, shaped their future, leaving the aspiring historian who is their great-granddaughter to attempt to imagine those crucial moments of choice and determined motivation.

Isabelle S. Headrick is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Texas at Austin. She works on the global modern education movement and its interaction with Iranian, Jewish, global French, and family histories. She wishes to thank Daniel Headrick and Kate Ezra for sharing their historical and photographic sources.