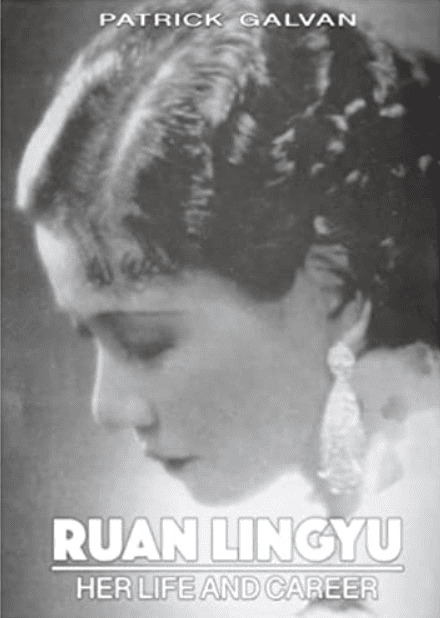

A child of poverty, luckless in love, her hour upon the stage mostly lost to history, and dead before the age of 25: all too true for Chinese silent film star Ruan Lingyu. Yet there was also a prophecy that “her artistry will one day serve all mankind,” and this too has proved true. The slim yet thorough and persuasive new book Ruan Lingyu: Her Life and Career by Patrick Galvan explains the contradiction, the tug-of-war between tragedy and imperishability that defines so many of the 20th century’s great artists. After reading it, no one could exclude Ruan Lingyu from the pantheon.

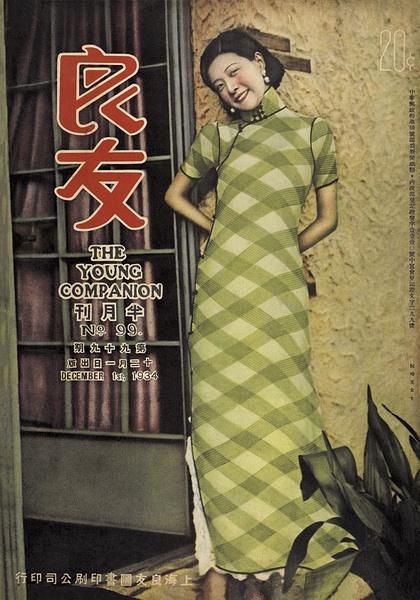

Galvan’s study follows the parallel paths of Ruan Lingyu, born Ruan Fenggen in 1910 to Cantonese migrant workers, and the Shanghai-based film industry of the young Republic of China. There were growing pains for both. The Ruan family grew and then shrunk, wounded by toil and illness. Young Lingyu found work as a movie actress, not an entirely respectable profession, but one poised to come into its own as the medium grew in popularity and matured in technique. Chinese films struggled to compete with more popular Hollywood imports, and Chinese directors struggled with low budgets and capricious government censorship. What got audiences hooked was not so much the martial arts spectacles and romantic melodramas, but the stunning actresses who appeared in nearly every movie from their respective studios. Popular polls consistently ranked Ruan Lingyu near the top of the list of Chinese starlets, and after her untimely death in 1935 she became a bonafide legend, her story inspiring movies (see 1991’s Center Stage) and TV miniseries (in 1985, 1988, and 2005) decades later.

“Growing pains” is not quite the phrase to describe the tumult in Ruan’s short life and in the Chinese silent film industry. One grows out of growing pains; neither Ruan nor her kind of cinema outlived their moment, as Ruan died young and once-powerful studios folded amid the shift to talkies and political upheavals that truncated many creative careers. Yet their painful and ultimately fatal struggles were rewarded with growth of a sort. Galvan expertly recounts the dense years of the late 1920s and early 1930s, specifically the effects of internal Chinese politics and the Japanese invasion on the nation’s movies. In the wake of the patriotic May Fourth Movement of 1919, domestic film studios gained ground against foreign-owned studios. By the mid-1920s up to 60 production companies of varying size operated in Shanghai, collectively releasing hundreds of shorts and ever-more features per year, but the 1930s brought economic and political crises that radically changed China’s film landscape. While telling this larger story Galvan summarizes of each of Ruan’s films, a great many of which are lost, with close attention to how their fictional narratives reflected and challenged prevailing ideas about gender, class, and nationhood.

Concerned about leftist content in popular media, the government of Chiang Kai-shek provided studios with a list of prohibited themes, and censorship became more strict after 1931 when the Nationalist government contended with both an internal communist threat and an external Japanese one. Depicting social problems was acceptable as long as movies did not suggest solutions or issue calls to action, since this would be tantamount to supporting revolution. Even with such restrictions, directors and cinematographers became more confident in their craft, and their stories tended to become more ambitious and nuanced. Ruan and her costars became more sophisticated performers, and Ruan in particular reached such heights that later critics compared her to Brando in terms of her ability to convey depth and authenticity.

Galvan’s book is primarily a work of history, not film criticism, but he does not shy away from assessing the merit of Ruan’s work, which varied depending on the studio, director, and subject matter. 1934’s The Goddess and 1935’s New Woman receive especially detailed attention befitting these films superior quality and messaging. Director Wu Yonggang’s The Goddess is “a hauntingly emotional portrait” of a Shanghai sex worker and her child that features creative camera work and Ruan’s most harrowing extant performance. New Woman is based partly on the short life of novelist and screenwriter Ai Xia, the second woman to author a Chinese feature film, and its critiques of social injustice make it “the most aggressively left-wing film in Ruan Lingyu’s career.”

Galvan is passionate when writing about the relationships in Ruan’s life. They were the source of the tabloid controversies that dogged her in her final months, and they likely played a key role in her two suicide attempts, the second of which was successful. She had two common-law marriages, the first of which fell apart due to financial stress brought on by her partner’s gambling addiction. Her second partner was violent and jealous and reportedly falsified Ruan’s suicide notes. Galvan’s notes and wording are precise, but one may still wonder about facets of Ruan’s life that never entered the written record and whether it is fair to speculate, as the tabloids did, on the circumstances of her death. Still, Galvan’s evidence-based assessments feel correct.

Ruan Lingyu: Her Life and Career is divided into chronological chapters with subheadings for her over two-dozen films. The subheadings note if films are lost, making the book an easy-to-use guide for readers who want to familiarize themselves with Ruan’s filmography. Most of her surviving films are easy to access in the internet age, and Galvan helpfully notes when this is not the case. His chosen images are generally high-quality or highest-available quality, and they depict a range of Ruan performances while also centering the particular aesthetic that made her stand out from her cohort. Galvan finds opportunities to contextualize Ruan’s career in comparison to some of her leading peers, many of whom shared remembrances of her over the years. The book also points to larger themes in Chinese film history, such as the challenges of being a Cantonese-speaker (as Ruan was) in a Mandarin-oriented industry as it shifted to sound in the 1930s, how the center(s) of Chinese-language filmmaking shifted to Hong Kong and Taiwan after the communist victory in 1949, and the effect of the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s on the old guard of mainland filmmaking.

And what of the prediction of one Chinese critic, who used the pen name “Yun,” that Ruan’s talent would one day benefit all humanity? Yun likely hoped that the actress would promote social change through her powerful performances in topical movies that spotlighted social problems and national crises. Whether Ruan or her films actually affected the trajectory of history is one measure of success, but as we approach the centennial of Ruan’s 1927 big-screen debut there is another, equally important legacy to consider. Ruan’s work now serves as a window to the past, a body of evidence about what hardworking filmmakers wanted people to know and think about at crucial, contested moments in Chinese history. Thanks to Ruan’s talent, it is a window we can enjoy gazing through.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.