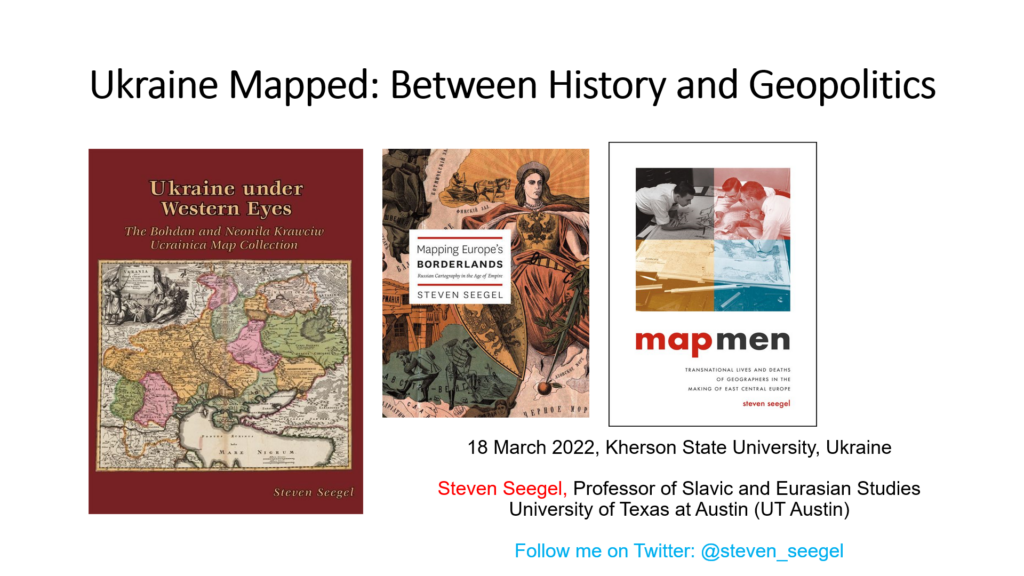

One year ago, on March 18th, 2022, I was lecturing via Zoom on the history of Ukraine and Ukrainian cartography in the city of Kherson. My public talk to a classroom of students, faculty, and administrators was entitled “Ukraine Mapped: Between History and Geopolitics.”

My talk was not normal. Kherson is a strategic port city in Ukraine today, about the size of Pittsburgh or Cincinnati or my post-Rust Belt hometown of Buffalo, New York. My lecture took place in a Zoom chamber, with a war outside. Checkpoints were blocked. The audience was besieged. I spoke to Ukrainians about map uses and abuses as Russians were killing Ukrainian Russophone soldiers and as Ukrainian civilians were getting shelled. From the outset, I struggled to find the right tone. Should I be muted or melodramatic? Deliberately shaky? Show propaganda? Be sober or exhortative? How should I teach or commemorate a map? Was it right to urge other perspectives and voices? How asymmetrical it was to be “westplaining” Ukraine during war, even though I’ve been active in Ukrainian Studies (doing research in 10 languages) for over twenty years. My space remains a relatively privileged vantage point in Texas.

I’m a historian of maps, archives, and geography. I tried to do what I could.

On that day a year ago, my 45-minute lecture turned into a two-hour conversation. I started by talking “to” the occupied. I had no idea how to start, and I haven’t shared this until now. How I began: “In times of war, every map becomes a weapon. You need maps now, very desperately, to see where enemy troops are stationed, how they are actively attacking. Maps are useful. They gather people into a snapshot. You assemble now against threats no one else can comprehend, to exercise your rights as citizens. Americans are arrogant bastards, so I am not here to tell you how to make choices. That’s your business. You’ve studied your history. You live in a sovereign, independent Ukraine. You have used your intelligence to elect your officials in local government and the Rada [parliament], based on manipulated lines. These lines were drawn by mapmakers whom you’ve probably never met, or will meet. In times of peace, we forget about the power of maps because they seem so ordinary. Apps on our phones. Demographics. Migration. Money makes maps. Power puts books into libraries and artifacts into museums. Maps of Ukraine, now attacked on at least three and likely four fronts, are something to hang on the wall as nostalgic mementos, curiosities, or patriotic gestures. There’s no time for that anymore here on the 18th of March, as you experience life and death. Yet we use maps all the time: for walking around, getting from place to place. They can kill us. Maps will kill you. Geolocation can kill your population, your civilians, as we know from Mariupol. You are in Kherson, and I am not.”

All to say: I didn’t want to lecture “at” the Khersonians. Indeed, Ukrainians–citizens of a country of 44 million people–do not need to be re-told their tragedies; or that they are permanent victims of decolonization; or that, as Europeans, they “have agency.” Since the annexation of Crimea by Putin’s forces in March 2014 and the start of the Russian-separatist backed war in Donbas, which has resulted in the loss of 14,000 lives on the Ukrainian side, Ukrainian civic identity and agency have been toughened. Ukrainians in the defense forces fight for a future EU-in-Ukraine and Ukraine in the EU. Americans are volunteering to fight alongside Ukrainians in legions of the Ukrainian armed forces. There are prayerful Muslims, devout Christians, and practicing Jews in Ukraine. Ukraine has multiple frames, multiple maps, and multiple histories. Poets know this well, as do decolonial literary scholars and historians. Yuri Andrukhovych, Serhii Zhadan, Oksana Zabuzhko, Andrei Kurkov, Oksana Lutsyshyna, and many more. Ukraine has a revolutionary past characterized by a struggle for civil rights, transparency and democracy not merely in 2013-14 or 2004, but also throughout a long, protracted fight for independence. This extended through two world wars.

Early modern Ukraine was located at the crossroads of empires. Modern Ukraine, facing Soviet promotion and demotion of Ukrainization, political and geopolitical issues of collaboration, and ultimate erasure, was a land and a people in between. This was true even during the period of Soviet Ukraine.

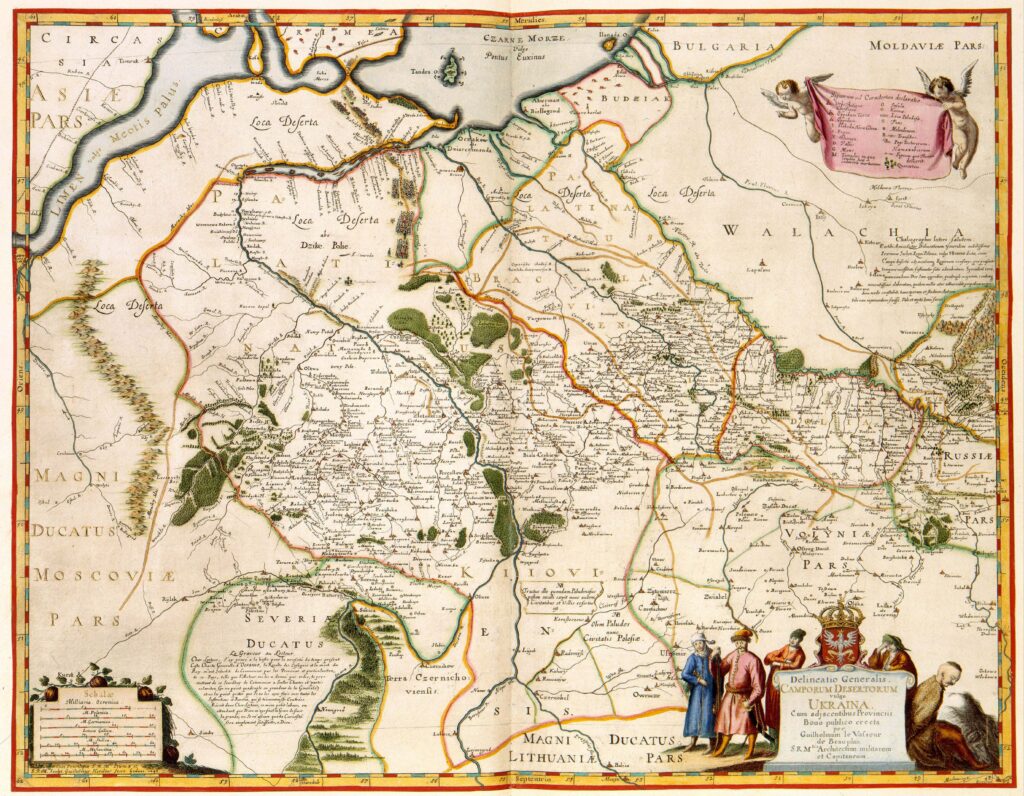

The geography of Ukraine’s imperial and postimperial borderlands should be better known: Sweden; Poland-Lithuania; the Romanov dynasty; the Habsburg Empire (later Austria-Hungary); the early modern Cossack Hetmanate, a proto-state and perhaps a proto-Empire; the Ottoman empire; and of course, Crimea. Every map is a prejudice, a blind spot, a way to avoid facts. People look at maps to live in myth and avoid history, in the way that Putin does. Or rather, to turn everything into geopolitics and geoeconomics. G20 into G8, G8 into G7, G7 into G2 (or G3). Great power imperialism, colonialism, neo-Stalinism, neo-fascism. When I first studied Ukrainian history as part of the Harvard Summer School, I learned from Professors Yaroslav Hrystak and Timothy Snyder the historical regions of Ukraine: Transcarpathia, Halychyna/Galicia, Volhynia, Podolia, Left- and Right-Bank Ukraine, Kyiv, Chernihiv, Siberia, Sloboda Ukraina, Bukovina, Donbas, Crimea. Hrytsak brought maps designed by Paul Robert Magocsi, another prominent historian and cartographer now in Toronto.

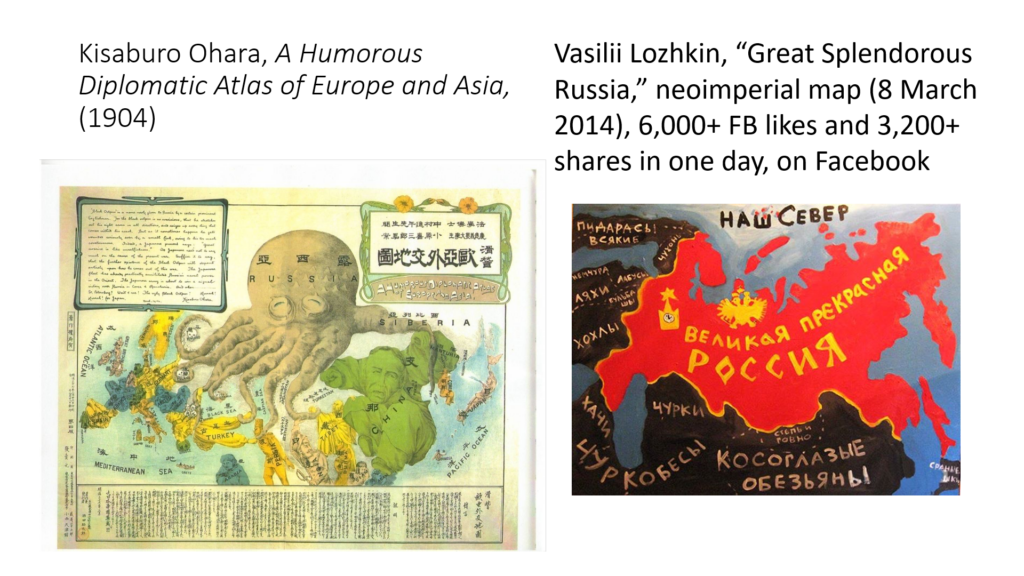

Putin is a dictator. He refuses all of this. Let it be told: he wants to exit his bunker in a mythic time, during the neocolonial Soviet Russocentric world of May 9th, 1945, otherwise known as Victory Day. Conquest and territorial revision, with new maps. He denies a genocidal policy, or any connection to European fascism in current Russian politics, or that there is any such thing as modern Ukrainian history or democracy in independent Ukraine.

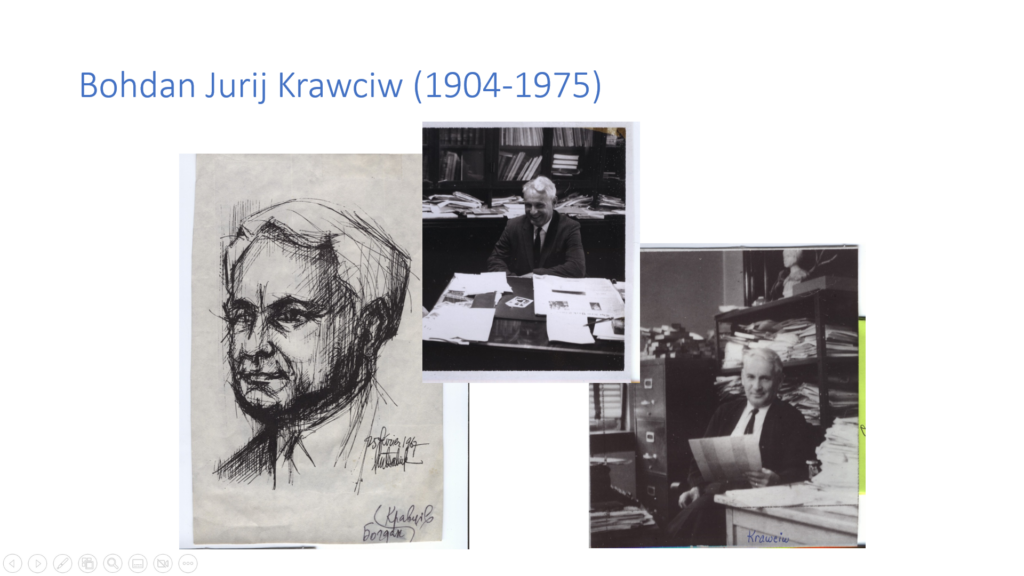

Ukrainians have a new day, February 24th, 2022. That also seems imperfect to me. I have come to share long stories of Ukrainian maps over many wars, transnational Ukrainian-Polish and Ukrainian Jewish and German-Ukrainian histories, how conflicts and coexistence came to be–and were–developed and preserved. Maps, too. After the Orange Revolution of 2004 in Ukraine, when I was still a Ph.D. student at Brown University, a substantial collection of 900 maps was donated by the family of a famous Ukrainian poet-journalist to Harvard University. I wrote a book about it, in which I curated a private collection of maps donated by the Ukrainian Bohdan Krawciw (1904-1975), who came from an important family in the North American diaspora. He became much loved by experts, for his translations of Rainer Maria Rilke from German into Ukrainian. Krawciw was influential, and is counted among the founders of HURI, the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.

In the lecture, I displayed these maps of Ukraine, mine and Bohdan Krawciw’s, at a moment when the Kremlin was trying to destroy the country, its people and history. All part of a fair commemoration now in mid-2023, though I’m not sure how to do it in the face of Putin’s denial of genocide and the Kremlin’s ridiculously Goebbelsian propaganda. Pundits (some, anyway) continue to urge Ukrainians to sue for a “peace” that 90% of the population regards as a surrender to a brutal occupation and genocidal policy. The EU and NATO security environments are pro-Ukrainian; they have also been changed substantially in just a year. For many, the February 24th date is a convenient start to the war. Don’t all wars need a convenient starting and ending date? I’ll return to this.

Some non-specialists think of independent Ukraine even after 1991–the independent state existed for much longer–as a borderland or a “former Soviet” space that somehow lacked agency and was mapped by others. But Ukraine has a long history–running straight up to the present–of independent agency, and it is full of groups and individuals with agency and historical rights and claims that clearly have histories (in the plural). Ukraine is not blameless: it has its own history of Holocaust collaboration, pink “greater Ukraine” maps, and Eurocentric and (neo)colonial traditions in cartography. This independent country of 44 million people, with now roughly eight million displaced people, has a rich and unacknowledged history of geography. Ukraine has even richer histories of cities beyond Kyiv, provinces and zones of contact, and regional geographies.

The founder of modern Ukrainian cartography, the “map man” Stepan Rudnyts’kyi (1877-1937), was a geoscientist (we’d now say) and a speaker of Ukrainian, German and Polish. Mapping out of Habsburg Galicia, he was born to a German world of European empires. Though he had hoped in build a school for the study of Ukrainian geography, and in fact moved from Vienna and Prague to Kharkiv in the 1920s, Rudnyts’kyi was arrested by the NKVD in 1933 and murdered during Stalin’s purges in 1937. He was a victim and an agent of history, a storied and layered cartographic architect of modern Ukrainian politics.

The experience of lecturing to the residents of occupied Kherson showed me that war commemoration doesn’t work. We tend to think of history in time and maps in space, with wars having a clear beginning and an end, the guns going quiet on the front, the roads demined, or the flowers blooming again from the trenches. In reality, wars are muddy and messy, and so are the maps that tell their stories. War anniversaries propped up by historians strike me as odd. As any student who has designed or examined one in an archive can tell you, maps require frames. Yet something is always distorted, or left out. Maps of Ukraine in 2023 show us fluctuating borders: worlds of hope and fear, desire and impermanence. Their details speak of loss, and of the human stories of unquantifiable pain. I post endless maps on my Twitter feed, but I am also aware of the ineffable and the intangible. Not all of this can be mapped: long memories of forcible displacement or removal might go unearthed for generations. Traumas of famine and genocide in Ukraine aren’t digestible, and often decades will pass before they get told, until we write them, map them, relive them.

It is an existential matter. Khersonians knew they could be killed for maps, and as a result, some mobilized very quietly (or not at all). Despite my evident obsession with cartography, maps are not just for describing what’s already been. They are futuristic. Maps draft and anticipate hopes and dreams. They are tools to guide us, instrumentalize (often dangerously) and explicate, interpret new worlds spatially, and help us along. As I said to Khersonians, “Kherson today should be mapped into Ukrainian history as well as Russian history, Greek history, Jewish history . . . social history, LGBTQ+/gender history, feminist history, and many other histories. It makes little sense to me to think of fabricated fictions like ‘Novorossiya’ or ‘Russkii mir’ or other such pretexts for re-colonized empires and destroyed populations. The Kremlin wants you to leave, and at this point, three weeks into its war, it probably wants you destroyed. Mainly as a scholar, I think maps are failed claims and arguments, or rather questions that anticipate failed arguments. Clearly, Mr. Putin’s mental map is of a new world order, with Russia (and Moscow, and himself, because he allows no elections and considers no alternatives) at the center of everything, backed by military, siloviki, security services, and armed police. Maps are a means to his end, and those who do not agree with his world maps can be eliminated.”

The future of Kherson and of Ukraine was in doubt now, and to some extent, remains in doubt. I now know that the people I’d “met on Zoom” were busy arming the resistance, even as they wondered about the checkpoints and fates of their families. There was no romance to any of it: it was dangerous there since the start of the escalated war. I compare this map imaginary to occupied Warsaw or Lwów/Lviv/Lvov/Lemberg (and many, many other Ukrainian or Soviet Ukrainian multicultural cities) during World War II.

The talk I gave to Khersonians on March 18th, 2022 took place several months before the successful Ukrainian counter-offensive of August 29th–November 9th, 2022. Ukrainian defense forces effectively liberated the city. But Russian forces continue to launch terror attacks on the city and the civilians within it. Students and young professionals who have been forcibly displaced express fears of going back there permanently to live, work, and story. Some do it anyway, like Kherson’s hunted, recently profiled, heroic mayor.

One year on, I think of my connection to the people of Kherson as a kind of emotional transnational map, a bond of global solidarity. The lecture went on, after which point the students went to sleep in the dormitory rooms, hoping to avoid missile attack. My audience had assembled at Kherson State University. Through the first month of the war, I had watched Russian missiles literally destroy university offices and classrooms where some of my colleagues had been teaching. I tried hard to get people to pay attention, in my Twitter feed and elsewhere. I am a public-facing historian, a historical geographer and an academic, but I know now that the people in my audience had special, rare courage. Their “public” was a civic space in war. Young and old, they studied maps. They had put up heroic resistance in defense of a Ukraine rich in traditions and history, right in the center of their city. Not virtue signaling, or merely performative in the ways of the West when they sang Ukrainian songs or waved Ukrainian flags.

In my talk on the Krawciw Ucrainica Map Collection and Ukraine’s history, I showed how Sweden, the Ottoman Empire, then Dutch, German and Italian cartographers drew from Renaissance and early modern mappings of the country. One of the centerpieces was the famous mid-17th century maps of “Ukraine” (so noted) by Guillaume le Vasseur de Beauplan (c. 1600-1673), who served the king of Poland-Lithuania as a military topographer, hydrographer, and cartographer. In Kherson beyond Russia, I literally had no idea where to start or what to do or say, what tone to choose. But we managed, and we did it together because we knew that Ukraine had a history. It has a history. Ukrainians have fought back, for a future Ukraine. They remember the Euromaidan protests in November 2013, and the forcible annexation of Crimea by the Kremlin during March 2014. I signaled for Putin’s Russia to return to history, not myth. Ukraine was not Russia, I intoned, and Russia is not the center of all maps.

We must pay attention to such maps and how Ukraine is mapped. What maps did to the Khersonians in March 2022 is something the world is only starting to process as war crimes investigators move in. The Crimean annexation of 2014, the siege of Sarajevo and genocide in Bosnia, the Budapest memorandum of 1994, the partition of India in 1947, the occupation zones of Berlin, the fate of Poland at Yalta, the annexation of the Sudetenland and then Austria in 1938, the world of national self-determination that failed under US President Woodrow Wilson, the end of Europe’s great power empires in 1917 and 1918, the Berlin Conference carving up the map of Africa, the partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793, and 1795. Ukraine mapped geopolitically is its curse, like partitioned Poland in the 19th century, or Soviet Belarus after 1921. I concluded, “Maps of Ukraine are sites of famine, genocide, ideological claims to power, and modern (and now postmodern) mass death. But maps of Ukraine also suggest peace. We pay attention to your maps, because they connect us. Maps have life. Those lives of Ukrainians I know and love bring me here with you. And those lives give me hope, as you do, to resist.” The work done by war crimes investigators will need to be combined with the history of maps and Ukraine’s tragedies to further contextualize the larger stories of population displacement, ethnic cleaning, and genocide.

Maps can help us resist, by speaking truth to power. But this is difficult in a place like Ukraine with all its historical regions, because maps are power. I can explain these imperfect tools and artifacts on my channels of history, and I would like to think of map history as a noble cause. It is not. My writing or lecturing about Ukraine’s history can’t stop the mass death. This was apparent to me in Kherson on March 18th, 2022. And while I wish I knew how to commemorate a war, I’m still figuring out how to speak to a Ukrainian audience, and how to give them the maps to resist an occupation. I don’t, but I will.

I will never forget that lecture in Kherson.

Steven Seegel is Professor of Slavic and Eurasian Studies at The University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of Map Men: Transnational Lives and Deaths of Geographers in the Making of East Central Europe (University of Chicago Press, 2018), Ukraine under Western Eyes (Harvard University Press, 2013), and Mapping Europe’s Borderlands: Russian Cartography in the Age of Empire (University of Chicago Press, 2012). He has been a contributor to the fourth and fifth volumes of Chicago’s international history of cartography series, and has translated over 300 entries from Russian and Polish for the US Holocaust Memorial Museum‘s Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, in multiple volumes, published jointly by USHMM and Indiana University Press. Professor Seegel is a former director at Harvard University of the Ukrainian Research Institute‘s summer exchange program. He is active on Twitter @steven_seegel and currently as the host of author-feature podcast interviews on the popular New Books Network. He is the founder of The February 24th Archive, an ongoing community-driven digital project (with 1000s of threads, 8 GB of tweets, 15 million people in terms of audience reach) that focuses on building global solidarities during Russia’s war against Ukraine.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.