In 2018, I was on a research expedition in Caracas, Venezuela. My days were filled with scheduling visits to libraries and repositories to start research for my dissertation on foreign oil companies and their activities in twentieth-century Venezuela. One sunny afternoon, an old mentor from my undergraduate years invited me to his private club. We were joined by another historian who shared an interest in my Ph.D. research at the University of Texas at Austin.

Sitting beside the swimming pool, our conversation revolved around our respective research projects. It quickly became evident that accessing primary sources in Venezuela posed a significant challenge. To start, there was minimal online information available. Most public and private libraries lacked online repositories accessible to researchers. Furthermore, many of the country’s archives and libraries were in dire condition. Underfunded and understaffed, they needed help to keep their doors open. To make matters worse, they had to limit their weekly operating hours.

Aware of these hurdles, my colleague, Guillermo Guzmán, and I began contemplating ways to preserve the country’s cultural heritage. Over the next few months, we explored various avenues to address this problem. Our attempts to secure funding for digitizing historical collections from the National Assembly (the equivalent of the U.S. Congress) proved futile. It soon became apparent that, as individual researchers, obtaining financial resources for digitization projects was an uphill battle. The logical step was establishing an organization dedicated to preserving the country’s history.

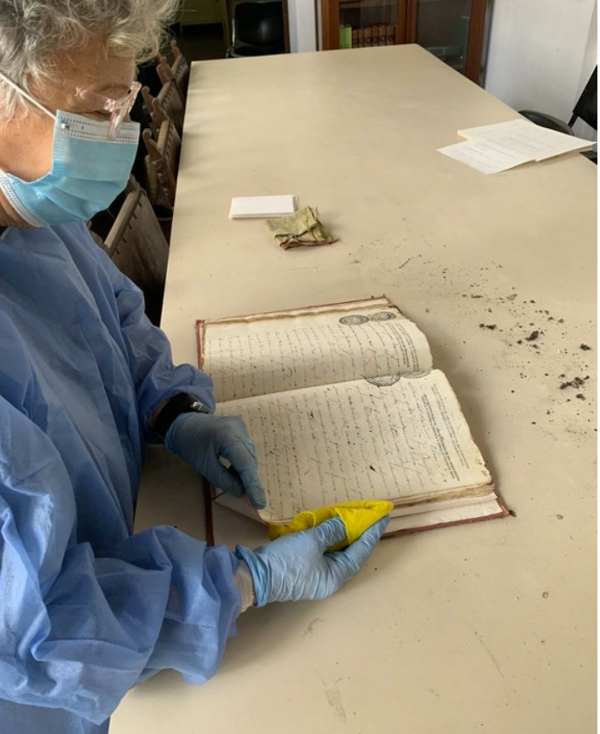

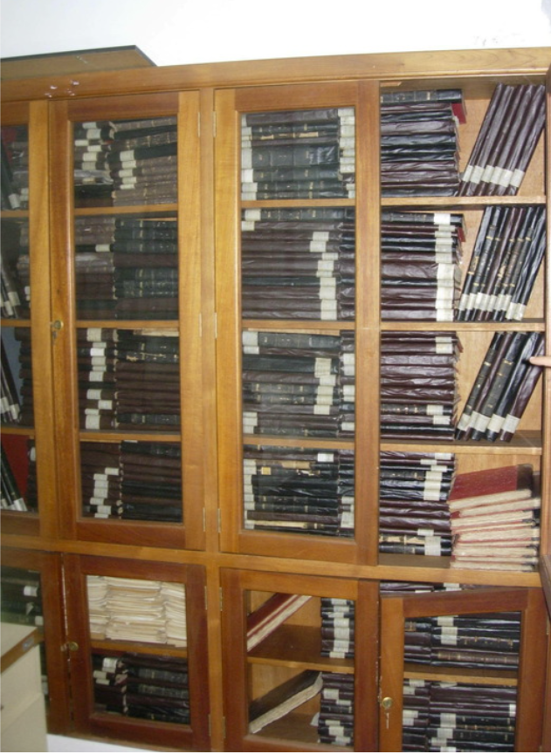

Incorporated in Venezuela and founded in 2021, the Fundación Red de Historia Digital Venezolana, known in English as The Venezuela History Network, simplified the application process for international grants. As this initiative unfolded, we were contacted by the National Academy of History of Venezuela, a prestigious public institution with a rich tradition of physically preserving archival materials and generating new knowledge about Venezuela’s and Latin America’s past. One of its colonial collections, the Civil-Slaves Section, faced infrastructural issues. This repository’s contents document the trials, civil cases, and petitions for freedom involving enslaved Afro-Venezuelans. Severe rains at the end of 2020 had compromised the ceiling where the collection was stored, prompting the archivists to relocate it. This institution sought our assistance in digitally preserving the collection. Through an inter-institutional agreement between the Venezuela History Network and the National Academy of History, we devised a plan to initiate the digitization of the Civil-Slaves Section. We also started looking for international grants. Our best supporter emerged in the form of the Gerda Henkel Stiftung from Germany. Thanks to the generous support of the Gerda Henkel Stiftung in 2022, the Venezuela History Network embarked on a digitization and preservation project for the Civil-Slaves Section.

After eight months of intensive labor, the project concluded. The Venezuela History Network successfully digitized 381 bound volumes and 23 boxes containing unbound documents, totaling 123,800 pages or 61,900 digital captures. This collaborative effort also facilitated infrastructural improvements to the room housing the collection, the acquisition of essential equipment such as scanners and laptops, and the creation of our current website and open-access digital library. Notably, this project allowed our team of paleographers, archivists, and researchers to train in best practices for digitizing historical materials. It’s worth mentioning that neither the Venezuela History Network nor the National Academy of History had any prior experience with digitization and metadata creation. The Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts provided the necessary training to accomplish this vital task.

The successful execution of the digitization project on the history of enslaved Afro-Venezuelans enabled us to reach new audiences. We promoted this new collection through online channels, social media, and public events, such as the one hosted at the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas in Austin in October 2022. This first effort brought forth new challenges as well. In 2023, we were given numerous opportunities to digitize additional historical archives and diversify our collections catalog. Currently, the Venezuela History Network is engaged in at least six ongoing or soon-to-commence projects in collaboration with prestigious organizations like the Modern Endangered Archives Program at the University of California Los Angeles and the Center for Research Libraries through the Latin American Material Project (LAMP) initiative. We plan to create collections covering the history of Cocoa, the private papers of former Venezuelan presidents, two cultural and political magazines from the twentieth century, and an archive documenting the HIV and LGBTQIA+ movements in the upcoming year. These initiatives are collaborative efforts involving public institutions, private individuals, and non-profit organizations. We’ve also presented our mission at universities, local radio and YouTube channels, and even tech events in Las Vegas, of all places! Although we remain a relatively small organization, the Venezuela History Network is eager to establish new partnerships and connect with individuals interested in collaborating with us.

In my capacity as a historian, these achievements have illuminated a profound truth: that we can do more as activists, historians and social entrepreneurs. History should serve a purpose beyond academia. In my case, I am contributing to the digital preservation of my country’s history. What’s more, through our open-access library, the Venezuela History Network is bringing history directly to the people, facilitating their reconnection with their own past.

The digital copies retained by our partners after each project’s completion ensure that, even if circumstances change in the future, the historical collections we are digitizing will endure. To further this cause, we also extend our assistance to local partners in getting their collections online. Admittedly, this isn’t a definitive solution. Our current scope of work remains confined primarily to Caracas and its surrounding areas. There exist numerous archives and libraries in other provinces that find themselves helpless. The country urgently requires substantial investments in the infrastructure and human capital of libraries and archives to genuinely safeguard our cultural heritage. In the meantime, the Venezuela History Network is endeavoring to fill this void, leveraging every bit of experience we gain to assist in this monumental undertaking. Through local and international alliances, we hope that new organizations and groups will join us in this titanic effort, hence the word network in the name of our institution.

The need to provide reliable and easy access to historical materials is crucial. Communities and individuals alike want to discover and access their own histories. If you’re a historian or another type of scholar with a drive or calling to contribute to the world of history, follow your instincts, get organized, and embark on collaborative work with your community. Your impact, however small, will leave an enduring legacy for generations to come.

Marcus Golding is a Ph.D. candidate in the History department. He holds a B.A. in Liberal Arts from Universidad Metropolitana in Caracas, Venezuela, and a M.A. in Latin American Studies from Georgetown University. Born and raised in Venezuela, Golding’s research interests as a Ph.D. student include business and labor histories in Latin America during the Cold War and the cultural, social, and economic influences of US petroleum businesses in the region and in Venezuela specifically. Marcus is also the co-founder of the Venezuela History Network, an organization focused on the digitization of archives at risk in Venezuela and the promotion of the digital humanities in general.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.