The legal cases of activists, including Angela Davis, Huey Newton, and the Chicago Seven, captured public attention throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Crowds crammed into courtrooms to watch these high-profile cases unfold, and many people became directly involved in efforts to free the defendants. While the United States has a long history of trying and imprisoning political dissidents, the decades following World War II witnessed a surge of public interest in such cases and the development of large and dynamic defense campaigns. Yet, the role that attorneys played in these campaigns—and within the broader movements that they represented—has been largely overlooked by historians.

As Luca Falciola reveals in his recent book, Up Against the Law: Radical Lawyers and Social Movements, 1960s-1970s, lawyers were indispensable to the progressive social movements of the period. They used their skills to defend radical activists who challenged the legitimacy of mainstream political institutions and promoted structural social change. Not only did these lawyers file briefs and argue in court, but they also formed personal relationships with their clients, participated in public protests, and became members of the organizations they represented. Most significantly, radical lawyers rejected conventional legal practices and transformed the courtroom into a platform for making political—rather than purely legal—arguments.

Up Against the Law documents this shift in legal practice and the emergence of what Falciola calls “militant litigation.” Attorneys associated with the National Lawyers Guild (NLG) played an outsized role in this process, and Falciola highlights this group’s members, politics, and programs. Founded in 1937, the NLG experienced a resurgence during the 1960s and became one of the leading progressive legal associations. Its members represented a range of activists, including those involved in the civil rights, anti-war, labor, Chicano, and prison movements. Lawyers affiliated with the NLG not only became actively involved in some of these movements, but they also gained new perspectives on the law and developed innovative legal strategies.

Source: Library of Congress

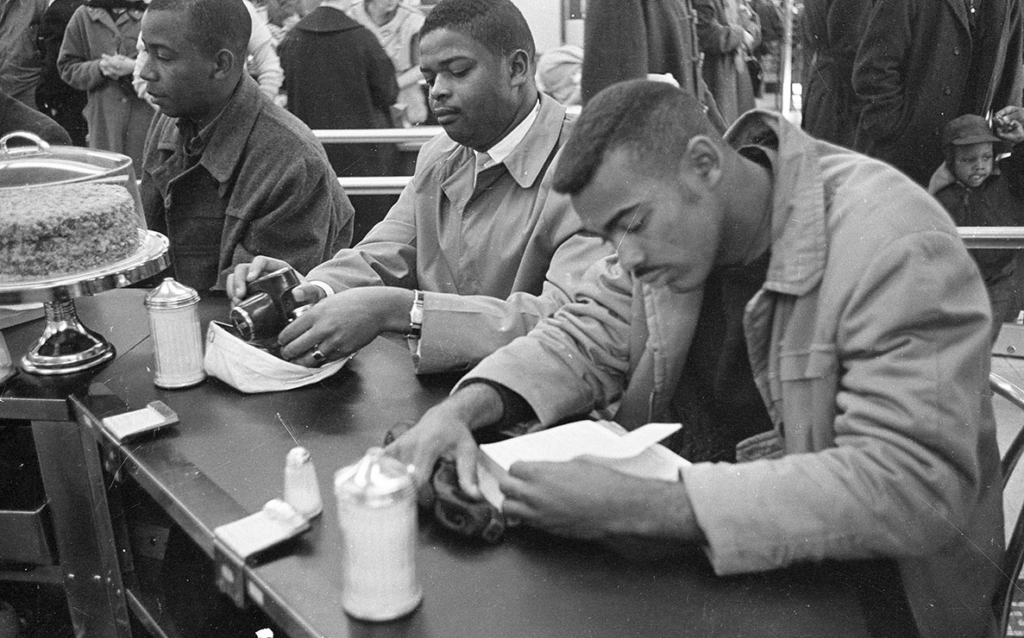

A range of sources informs Falciola’s argument, including court transcripts, organizational records, NLG literature, and perhaps most significantly, memoirs and correspondence from radical lawyers like William Kunstler and Charles Garry. As these sources reveal, involvement in the Southern civil rights movement was one of the most radicalizing experiences for NLG members. During the sit-in movement of the early 1960s, lawyers from northern states traveled south to Mississippi and Alabama, where they provided logistical and financial support to their southern counterparts. The brutal reality of the Jim Crow legal system and the lack of federal intervention shocked the organization’s predominantly white membership.

Traditional defense strategies proved futile in this environment, and the NLG was forced to develop a streamlined process for disbursing bail funds and representing the thousands of activists arrested. In Falciola’s words, this early movement work offered “a laboratory in which a new relationship between lawyers and activists could be forged” (p.279-80). Over the following decades, radical lawyers built upon and refined this relationship as they defended student activists, anti-war protesters, and other political prisoners.

These shifts within the NLG were especially visible in the courtroom. As radical lawyers began to see the law itself as an instrument of oppression, they experimented with strategies to minimize the impact of racism and discrimination in jury trials. They crafted questions designed to eliminate prejudiced jurors during the selection process, worked to secure changes of venue when a local climate proved hostile, secured testimony from expert witnesses, and undermined the authority of the prosecution by constructing compelling narratives about cases. Younger lawyers and law students also challenged traditional professional standards; they dressed casually, disregarded courtroom decorum, and questioned the hierarchical nature of their own organizations. As Falciola reveals, these critiques gave way to some more radical experiments in alternative legal practices. Lawyers in New York City and San Francisco, for instance, went so far as to create legal collectives that provided free services to clients and promoted public legal education.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Using the law as a tool to promote radical social change was an inherently contradictory and unsustainable goal. As Falciola writes, “An effective defense strategy was often incompatible with a full-fledged critique of the legal system or with a truly alternative law practice. Yet radical lawyers worked undoubtedly to combine these two goals and–at least for a while–they seemed to succeed” (p.79). Much of this early success began to unravel by the late 1970s. Like the activists they represented, these lawyers’ conflicts were exacerbated by internal disagreements and political repression. Yet, they would leave an indelible mark on the practice of law through their radical critiques, innovative strategies, and personal commitment to their clients’ causes.

This book provides an excellent overview of the mid-twentieth century’s major progressive social movements while shedding light on the underappreciated role of lawyers within these movements. The book’s impressive scope invites further research on specific cases that appear only briefly in the text while also providing a useful framework for conceptualizing the relationship between radical lawyers and their clients. While the book works well as an overview, Falciola does sacrifice breadth for depth in several places. In discussing the histories and platforms of organizations like the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement, for instance, Falciola glosses over important context and nuances. In some cases, he comes across as overly critical.

While the book’s focus on the NLG anchors the text and allows Falciola to examine legal cases associated with a wide range of social movements, it also leaves some questions unanswered. Radical lawyers who worked for other groups receive only brief consideration, while attorneys drawn to radical causes through personal relationships are almost entirely excluded. The cases of political prisoners Assata Shakur and Angela Davis, for instance, receive only brief attention; Shakur was represented by her aunt, Evelyn Williams, and Angela Davis’s childhood friend, Margaret Burnham, worked on her defense. This focus on attorneys associated with the NLG also minimizes political prisoners’ critical role in crafting their own defense strategies.

Ultimately, Up Against the Law offers readers a compact but thorough account of radical lawyers and social movements between the 1960s and 1970s. By emphasizing the key role that attorneys played in these movements, Falciola identifies the courtroom as an important site of protest and a space in which such movements were taking shape. Activists and lawyers transformed the courtroom into an arena where political ideas could be publicly debated. At the same time, they developed innovative strategies designed to put the criminal legal system on trial. Many of the ideas radical lawyers promoted—from client-centered law firms to more practical legal education—have gained currency in recent decades. In recounting this history, Falciola broadens our understanding of progressive social movements and their enduring impact on American jurisprudence. For this reason, the book is valuable and deserving of a wide readership.

Sarah Porter is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She studies twentieth-century social movements, policing, and mass incarceration in the United States.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.