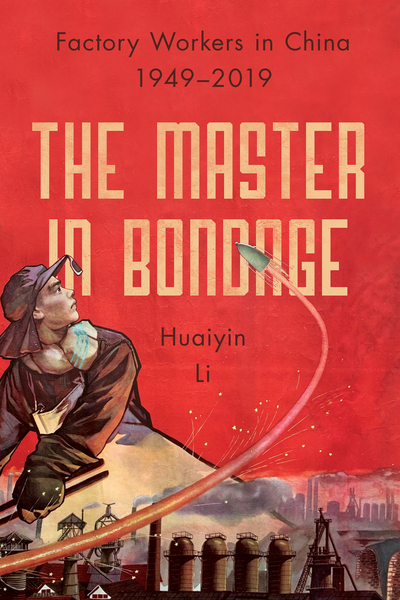

In my research on the social history of modern China, I have long focused, first, on how ordinary people lived their everyday life in a local community, such as a village, a production team, a factory or a workshop within it, during times of historical change. And, second, on how their personal experiences differed from what the organizations or movements imposed on them intended to be, and from what the master narratives told us about the events that involved the masses of local people. Before writing about factory workers in post-1949 China, I had published two books on peasant communities and agrarian changes in China before and after 1949, namely, Village Governance in North China, 1875-1936 (Stanford University Press, 2005) and Village China Under Socialism and Reform: A Micro-History, 1948-2008 (Stanford University Press, 2009). What I wanted to investigate in those two books was not so much about the formal, visible institutions operating in local communities, as it was about how such externally imposed institutions interplayed with the less visible, less formal institutions embedded in the village community to shape villagers’ day-to-day experiences.

I adopted a similar approach to studying factory workers. The Master in Bondage pays equal attention to both formal institutions and the subtle, less visible workplace practices. Its goal is not to assess whether the formal factory institutions succeeded or failed in executing their official functions as claimed by the state. Instead, it aims to explain how the imposed policies, systems, regulations, or organizations interacted with local practices and social relations to dictate worker performance in everyday production and factory politics.

The approach I employed in this book can be characterized as substantivist, meaning it seeks to contextualize formal, legal systems within the broader framework of informal relations and practices. It departs from the formalist approach that is often found in past studies, which focuses primarily on formal institutions and interprets individuals’ behavior as derivative from such institutions. For example, the “egalitarian” nature of the wage system in state-owned factories in the Maoist era lead many to believe that worker performance in production was necessarily subpar and inefficient; and the cadres’ extensive power in factory management also caused many to deduce their relationship with workers as one of domination and subordination. Workers in this light appeared to be either powerless and susceptible to cadre abuses or seeking favoritism from the powerful.

I do not deny the existence of issues such as inefficiency in production or favoritism in cadre-worker relations; they did indeed exist with varying intensity across different factories and time periods. My point is that factory life was much more complex and multifaceted than the formalist perspective suggests. Factory workers inhabited a social environment in which a diverse range of formal institutions and informal practices intermingled, both constraining and motivating them as individuals and as a group; their strategies and actions were far more varied and adaptable than what one would find in the formalist literature in academic publications or in the discourse prevalent in mainstream media in post-Mao China, which was often influenced by recently imported neoclassical economic theories.

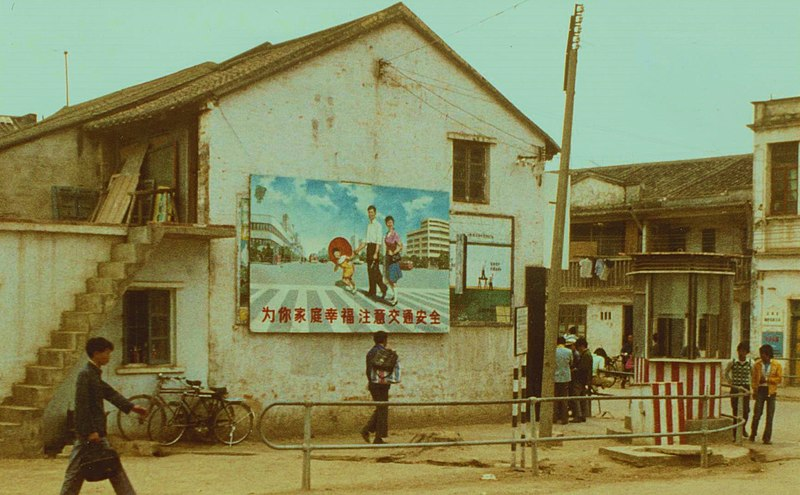

Source: Library of Congress.

This book is based primarily on interviews with 97 retirees from mostly large-size, state-owned factories in different parts of China (with a few exceptions of locally owned “collective firms”), which my collaborators and I conducted in 2012-2013. The method of using workers’ oral account for studying factory politics in contemporary China can be traced to the 1970s and early 1980s and even earlier, when the availability of refugees and emigrees from mainland China made it possible for researchers to conduct interview with them in Hong Kong.

In comparison, doing such interviews three decades later has its own merits and shortcomings. The shortcomings are obvious: for our informants, factory life under Mao belonged to the remote past, and many details about their experiences on the shop floor had faded from memory and become increasingly inaccurate as time went by. The merit is that, having experienced enterprise reforms and restructuring in the post-Mao years, which brought to them both improvements in living conditions and unprecedented frustrations because of unemployment or insecurity of livelihood, the workers’ attitude towards the Maoist past could be ambivalent: a mix of nostalgia and resentment are both present in their memories. Overall, however, a more balanced account of their life in state firms can be expected in comparison to the views expressed by the emigres of the 1970s and early 1980s, who witnessed huge contrasts between Hong Kong and mainland China, and whose account of their recent past tended to be highly selective and dismissive.

This book also draws on documents on factory governance preserved at the Nanjing Municipal Archives. Similar issues exist with the archives from the Mao era. Most of the files were produced by the management or “mass organizations” (trade union, the staff and workers’ congress – usually known as the SWC, and the youth league) of state firms. While they provide interesting details about the implementation of state policies and the firm’s own initiatives or about the activities of the mass organizations, these documents were written primarily to prove the necessity and effectiveness of such policies or measures, and the examples included in these reports were highly selective and one-sided in many cases. Therefore, caution is necessary when using these files. Despite the various flaws with oral histories and official archives, however, these sources turned out to be immensely valuable and informative for forming a well-rounded interpretation of factory politics in Maoist China and afterward.

My interpretation in this book revolves around “substantive governance,” a concept that I initially conceived in Village Governance in North China and further developed in this book. Instead of focusing on the officially defined goals and functions of factory institutions and evaluating their effectiveness by looking at how the operational realities of those institutions met their officially stated objectives, this concept instead emphasizes the real purposes of factory institutions and how their everyday operations fulfilled the factory’s actual needs in maintaining its functionality.

Take the trade union and the Worker’s Congress or SWC. By official definitions, these two organs were intended to be tools for workers to exercise their rights as the “masters” of the factory, enabling them to participate in the factory’s decision-making process and supervise enterprise management; post-Mao reformers further hailed these two organs as mechanisms of “grassroots democracy” presumably leading China to the future of political democratization at higher levels. But a close examination of the actual functioning of these two institutions shows that their only purposes were to satisfy workers’ everyday needs in production and subsistence in order to ensure the factory’s smooth operation; they had little to do with promoting workers’ social standing or political rights. Thus, while those institutions appeared to be a failure in the eyes of people aspiring to be the masters of the factory or promoting democracy in China, they worked effectively in satisfying the real-world needs of both the workers and the factory.

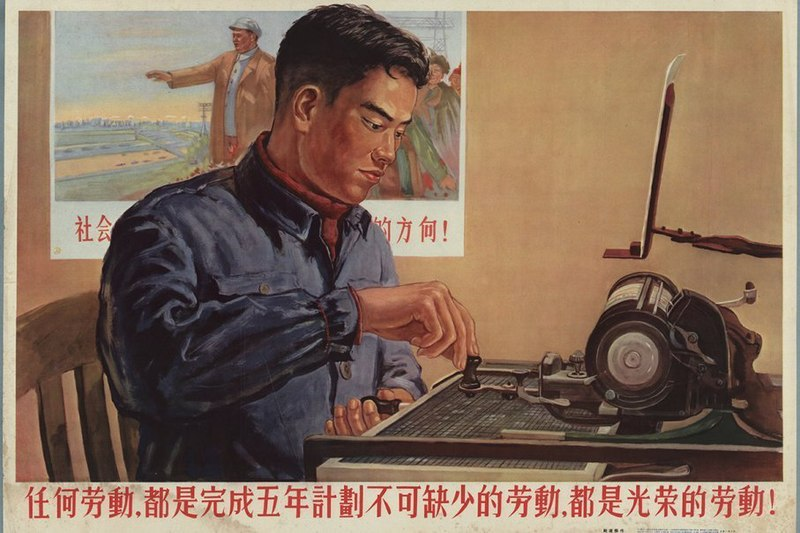

Source: Wikimedia Commons

At the core of the concept of substantive governance lies my analysis of the mechanisms of dual equilibrium in regulating worker performance in everyday production and power relations. Contrary to the prevailing narrative in China’s mainstream media that assumed widespread inefficiency in production in state firms because of egalitarianism in labor remuneration, most workers turned out to be neither fully dedicated to production as the Maoist representation of them as masters of the factory suggested, nor as slacking and negligent as the pro-reform elite made people believe after the death of Mao. In fact, how workers performed in production was subject to the functioning of two distinct sets of factors that interwove to constrain as well as motivate them. One was the formal institutions of lifetime employment guarantees, the wage system, labor discipline, workshop regulations, supervision by group leaders, daily political study meetings, and the nomination of advanced producers and model laborers, among others. The second was informal factors on the shop floor, such as peer pressure, group identity, and work norms among coworkers.

These two sets of factors converged to form a social context in which workers developed their strategies for everyday production. As our interviewees repeatedly confirmed, both those who aspired to be model laborers and those who overtly shirked were few; instead, most of them worked hard enough to meet the minimum requirements of factory regulations and disciplines in order to avoid being openly censured or criticized by supervisors. At the same time, however, they also managed to conform to the informal norms and attitudes that prevailed on the shop floor to avoid being ridiculed or complained by their peers. An equilibrium thus prevailed in labor relations, which explains why industrial production at the micro level was neither as terrible as taken for granted in the post-Mao discourse nor as efficient as the Mao-era state propaganda claimed.

The poster reads, “Whatever Work Aims to Complete and Not to Fail the Five-Year Plan, All That Work Is Glorious!”

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A similar equilibrium prevailed in power relations between cadres and workers in state-owned factories. Here again, two sets of factors worked together to dictate their relationship, giving rise to an equilibrium in it. One was the formal institutions of the SWC and the trade union, including the system of appeal by letter and visits to expose cadres’ injustice, the factory management’s lack of power to fire workers and change their wage grades, workers’ guaranteed lifetime employment and wage grades pegged with seniority, workers’ superiority in political discourse, and the recurrent political movements that target corrupt cadre

The second included informal factors and practices such as personal loyalty and friendship, cadres’ care of personal reputation among subordinates, their dependence on worker collaboration to fulfill production targets, and workers’ taken-for-granted rights to subsistence. It was in this context of both formal and informal institutions that workers defined who they were and how to deal with cadres. Contrary to the conventional wisdom that assumed the predominance of the patron-client network in factory politics, cadres’ favoritism was limited in nominating workers for honorary titles or recruiting new party members and even more difficult in determining wage raises, bonus distribution, and housing allocation. In fact, not only was it difficult for the cadres to practice favoritism openly, but given the huge risk of doing so under immense pressure from both above and below, most of our interviewees also believed it unnecessary to seek cadres’ peculiar favor and protection, given the security of their job and livelihood. Instead of workers’ personal dependence on cadres, what prevailed between the two sides was an overall balanced relationship, each having their own strength and leverage in dealing with the other.

The dual equilibrium in production and power relations suffered severe damage and, in many state firms, even disappeared during the first few years of the Cultural Revolution due to the chaos or stoppage of production and the paralysis of factory management as workers engaged in Red Guard rebellions and seizures of power, and most factory leaders stepped down. It re-emerged in the early 1970s when political disorder subsided, and most factories rebuilt their leadership, restored production, and reinforced labor discipline. However, it eventually collapsed in the 1980s and early 1990s as a result of economic reforms, which granted individual enterprises the power to hire and lay off workers and increase their wage or bonus payments. It was during this period of enterprise transformation, rather than in the years before it, as many of our informants observed, that cadres’ favoritism prevailed because of their greatly increased power in labor management and workers’ weakened position in relation to them. Similarly, it was also during the years of enterprise reform, rather than before it, that workers’ slacking and negligence in production became a severe problem, as many of them began to seek opportunities outside the factory for extra income and as bonus payment became the only tool to incentivize them.

The equilibrium in production and power relations was completely gone in the late 1990s and early 2000s when most state-owned factories were incorporated and turned into private businesses. Instead of being the master of their factory, a political status that they had enjoyed, at least rhetorically, in the Maoist past, workers became the vulnerable “master” of their own labor only, subject to enterprise management’s complete control and reckless abuses in the absence of effective labor law and an autonomous trade union to protect them.

Interestingly, it was during the privatization of state firms, when workers were confronted with the immediate danger of losing their privileges of lifetime employment and security of livelihood, that for the first time, they used the SWC as the legal weapon to defend their rights, as best seen in the case of Zhengzhou Paper Mill. In October 1999, workers of this paper mill occupied factory buildings when the mill was to be sold to a private firm. They further convened a SWC meeting to pass a resolution that demanded the termination of the merger. The workers succeeded when the city government approved the termination to avoid the worsening of the situation, but it refused to restore the paper mill into a state-owned enterprise as the workers originally requested. Instead, the paper mill was transformed into a shareholding company in the end, with its management board members elected by the company’s SWC.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

But such cases of successful resistance were rare. Millions of workers of former state firms suffered unemployment after their factories were privatized, and they were compensated with only a one-time payment by the new owners of the factories to “buy out” their seniority and the pension plan that came with it. Those who were lucky enough to be re-employed in the newly restructured firm became wage workers only, where the roles of the trade union and the SWC were marginalized and even nonexistent at all. Even less fortunate were the millions of migrant workers, who were hired as informal and temporary labor force, lacking the protection of labor law and eligibility for welfare benefits. While enterprise reforms propelled China’s industrial expansion and economic growth, workers’ income levels and living conditions, while improving over time, lagged steadily behind the growth of wealth they created.

In recent years, China has made huge efforts to upgrade its manufacturing industry and narrow its technological gap with the most advanced industrial nations. Key to this task, as many in China have observed, is the need to maintain a large, stable rank of skilled workers. Cultivating “the spirit of craftsmanship” (gongjiang jinsheng) among the workers thus has been a popular slogan that the party-state has vigorously promoted in its quest for China’s rise as an “advanced manufacturing power” (zhizhaoye qiangguo). Increasing workers’ wages and providing them with legal protection are no doubt effective tools to incentivize the workers. However, to make them not only technically competent but also fully dedicated to the workplace requires the cultivation among the new generation of the Chinese working class a shared sense of belonging to the workplace and pride over their workmanship. There is still a long way to go for a new type of equilibrium to resurface on the shop floor, where workers are treated more as members of a community than simply wage earners.

Huaiyin Li, Ph.D. from UCLA, teaches modern Chinese history at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of Village Governance of North China, 1879-1936 (Stanford, 2005), Village China under Socialism and Reform: A Microhistory, 1948-2008 (Stanford, 2009), Reinventing Modern China: Imagination and Authenticity in Chinese Historical Writing (Hawaii, 2012), The Making of the Modern Chinese State, 1600-1950 (Routledge, 2020), and The Master in Bondage: Factory Workers in China, 1949-2019 (Stanford, 2023). His latest article on the origins of Chinese civilization appears in The Journal of Asian Studies (Vol. 82, No.4, November 2023).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.