In The Sewards of New York, Thomas P. Slaughter offers a captivating exploration of the Seward family’s multifaceted place in the first half of the nineteenth century. Although not written as a traditional political biography, Slaughter emphasizes that “politics, and particularly the abolition of slavery” remains central to the Sewards’ collective story (p. 2). Slaughter looks beyond William Henry Seward’s political achievements in his roles as New York State Senator, Governor, U.S. Senator, and Secretary of State under Lincoln. Slaughter details a gendered history of a political family. He shifts the focus away from formal political record and toward the inner world of the Seward family, tracing the relationships, tensions, and experiences that shaped their lives.

Slaughter draws on newly rediscovered family correspondence and archival materials from the University of Rochester to illuminate the private world of William Henry Seward, his wife, Frances, their children, and broader family dynamics in Auburn, New York. Slaughter highlights that with the use of the “Seward family’s letters, we can look behind the curtain of the Victorian era’s private sphere to see life as it was experienced by other Americans” (p. 4). The book effectively argues that understanding the Seward family’s domestic life is essential to grasping the political landscape of their time. Through a rich tapestry of letters, the author connects the family’s personal experiences to significant societal changes, such as industrialization, expanding literacy, and evolving gender roles.

One of the strengths of the book is its accessibility. Slaughter combines scholarly rigor with engaging narration, making it suitable for both academic readers and general audiences. This is a testament to his deliberate effort to bridge the gap between academia and public readership, as evidenced by his recent transition to trade imprints. Reading through thousands of letters exchanged among multiple Seward family members over decades, Slaughter invites readers into the interwoven lives of a prominent political family navigating an intensely tumultuous moment in American history.

The narrative is not merely biographical; it highlights how private life was intertwined with the public sphere, especially during pivotal moments of life in the antebellum period and the Civil War. Slaughter’s exploration of Frances Seward is particularly striking in its engagement with a broader perspective on 19th-century gender roles and women’s leadership in the household. Slaughter emphasizes the sacrifices that the Seward family experienced as William Henry’s political career evolved; the Seward family began to “excuse his domestic limitations as son, sibling, husband, and father for the better part of another decade as prices they all had to pay for his dedication to the public interest” (p. 169).

Often overshadowed by her husband’s accomplishments, Frances emerges as a formidable force within the family, passionate, politically aware, and more progressive in her beliefs than her public persona suggests. Her correspondence sheds light on domestic ideals, gender constructions, and even spiritual movements of the era. While William Henry may have been the most famous Seward in Slaughter’s book, Frances’ story effectively takes center stage.

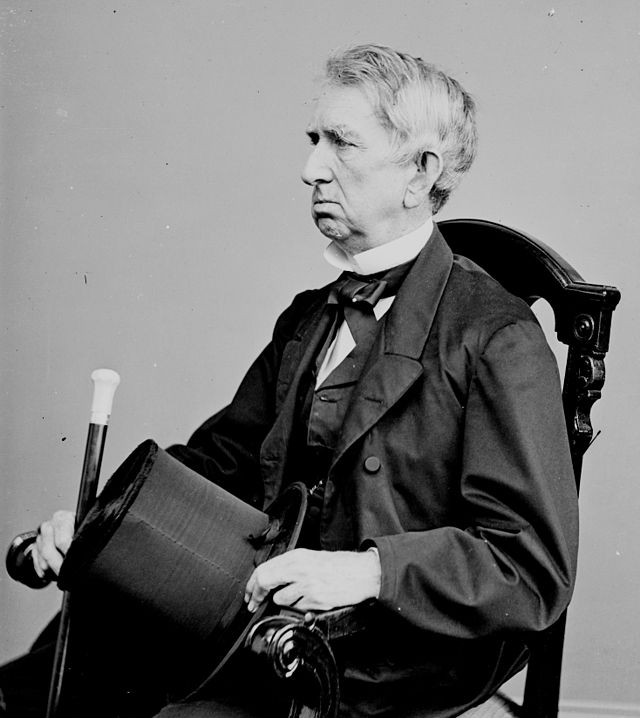

William Seward, Secretary of State of the U.S. Photo portrait ca. 1860-1865. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The book’s structure, supplemented by a detailed table of contents, allows readers to easily navigate through the family history from the 1820s to the early 1860s, making it ideal for those interested in case studies of political families. Each chapter covers a distinct period in the Sewards’ political and domestic lives. The themes of family ties, emotional resilience, and moral convictions are woven throughout, offering insights into how the Sewards navigated the complexities of their era, including issues of slavery and political upheaval.

A central theme in the Seward household is the private disconnect between Frances and William Henry. Slaughter’s detailed account restores Frances Seward’s agency, largely absent from the historical record for nearly two centuries. “Frances realized that it was not just his political ambition that kept her husband from home but rather his disdain for family life” (p. 239). Slaughter opens the reader to the perspective of life as a wife and family member of a significant political figure, and to the spiral of family issues that comes with it.

Portrait of Frances Adeline Miller Seward in 1844, by Henry Inman. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Slaughter’s The Sewards of New York is a poignant and enriching examination of a notable American political family. The author invites readers to engage with the Sewards not just as historical figures but as complex individuals whose lives reflect the broader societal transformations of their time. Unlike many political biographies, The Sewards of New foregrounds the domestic world that shaped nineteenth-century political life. Slaughter offers an example of how other authors may contribute by examining significant political families, focusing on how the historiography may shift depending on which figures are highlighted. It will undoubtedly serve as a valuable resource for anyone interested in early American history, political families, or the interplay between private life and public action.

Alec Ainsworth is a graduate student from Southern California in the Department of American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. He received a bachelor’s degree in American Studies and English at California State University, Fullerton.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.