Introduction: a figure at the margins

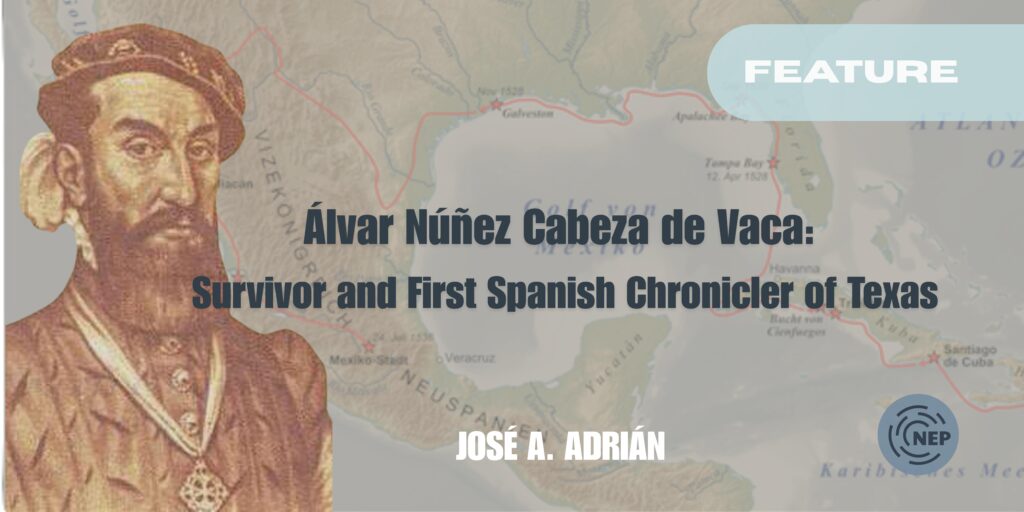

American historical memory abounds with the names of explorers and pioneers: Hernando de Soto, associated with the European discovery of the Mississippi; John Smith and the English settlers of Jamestown; the pilgrims of the Mayflower; and, in Texas, Davy Crockett and the Alamo have become mythic symbols. Yet few can easily recall the man who, long before all of them, wrote the first chronicle of what is now Texas: Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.

This contrast is not new. Cabeza de Vaca was never part of the traditional canon of explorers and pioneers; instead, he stands apart as a survivor who, out of necessity, became the first chronicler and an accidental ethnographer of the southern regions of what would later become the United States.

The Narváez expedition and its disastrous end

In 1527, Pánfilo de Narváez received the royal commission to conquer and settle the region then known as La Florida, a vast territory along the Gulf Coast. But the enterprise ended in disaster: shipwrecks, hunger, and clashes with Native peoples—particularly the Apalache—destroyed most of the expedition. Narváez departed with 600 men, but only four survived: Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes, Alonso del Castillo, and Estebanico, an enslaved man of Moroccan (or North African) origin.

In Naufragios (1555), Cabeza de Vaca himself described with stark honesty the misery of those days, when survival depended on begging for food, improvising cures, or submitting to the demands of Native peoples. His account reflects not a conquest, but a defeat that forced a rethinking of the relationship between Europeans and Indigenous communities.

Bust of Cabeza de Vaca in Houston, Texas. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Eight years on foot across North America

For nearly eight years, Cabeza de Vaca wandered on foot for thousands of miles across Southwest North America, from the Texas coast to northern Mexico. Born into the minor Andalusian nobility and trained as a royal official, he was utterly unprepared for what followed. He was a captive, an itinerant trader, and eventually a healer. He learned languages, participated in rituals, and acted as a mediator between rival groups.

One extraordinary episode shows both his vulnerability and the reputation that began to surround him:

“En aquella isla que he contado nos quisieron hacer físicos sin examinarnos ni pedirnos los títulos (…). Vi el enfermo que íbamos a curar que estaba muerto (…) y lo mejor que pude supliqué a nuestro Señor fuese servido de dar salud a aquél. Y después de santiguado, rezar un Pater noster y un Ave María y soplado muchas veces (…) dijeron que aquel que estaba muerto se había levantado bueno, se había paseado y comido con ellos.”

(“On that island I have mentioned, they wanted to make us into physicians without examining us or asking for credentials (…). I saw that the patient we were to cure was already dead (…) and as best I could I prayed to Our Lord to grant him health. After making the sign of the cross, reciting a Pater Noster and an Ave María, and breathing on him many times (…) they said that the one thought dead had risen well, had walked about, and had eaten with them.”)

It was medicine born less of science than of utter desperation. That experience transformed him—not because he set out to be more humane than other Spaniards, but because survival required him to navigate systems of violence, captivity, and coercion that did not fit his European frame of reference. He was no longer the Andalusian nobleman who had left Spain, but a man shaped by captivity, forced adaptation, and life on the margins of multiple Indigenous worlds.

Unlike Hernando de Soto, who led an armed expedition through the Southeast of what is now the United States and left a trail of violence, Cabeza de Vaca’s journey carried him far to the west and southwest, across much of present-day Texas and into northern Mexico. He survived through forced adaptation, negotiation, and the fragile accommodations of life on the margins. A clear map of Cabeza de Vaca’s route can help readers visualize the expansive westward trek that distinguished his journey from that of De Soto.

Expedition of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca 1528 bis 1536. Source: Wikimedia Commons

An early chronicle of Texas and the Southwest

The value of Naufragios lies not only in its spirit of adventure, but also in its status as the first written chronicle of Texas and the American Southwest. Within its pages, one encounters now-vanished peoples such as those later identified as the Karankawas and the Tonkawas, described in remarkable detail in their customs, social organization, and beliefs. More than a story of exploration, the work often reads almost like a proto-ethnography (long before anthropology existed as a discipline), attentive to daily life, ritual, and conflict resolution that few other chroniclers ever attempted.

A particularly revealing passage describes how disputes were resolved among these groups:

“Cuando tienen diferencias sobre algún negocio, pelean a puñadas hasta que se desbaratan la cara y todo el cuerpo de sangre; y después de quedar así maltratados se apartan y los suyos se meten entre ellos y los pacifican; y lo más admirable es que de allí en adelante quedan amigos y no queda memoria de la injuria pasada.”

(“When they have disagreements over some matter, they fight with their fists until their faces and bodies are covered in blood; then, once battered, they separate and their people step in to make peace. What is most remarkable is that from that point on they remain friends, with no memory of the injury suffered.”)

He also recalled the sheer physical toll of survival:

“…nos mandaban sacar raíces del fondo de los esteros, y con el agua y el esfuerzo se nos despellejaban manos y pies…”

(“…they ordered us to dig roots from the bottom of the swamps, and with the water and the effort our hands and feet were left raw and bleeding…”).

Far from the triumphalist tone of other chronicles of the Indies, Cabeza de Vaca’s work is the testimony of a man stripped bare, who observes and narrates not from the posture of conquest, but from the exposed and precarious position of a man forced to survive at the edges of multiple Indigenous worlds.

Legacy and memory

Despite the significance of his experience, Cabeza de Vaca has not become a central figure in wider American or Texan public memory. While he has never disappeared from scholarly work—and even has a statue in Houston—his life and legacy remain deeply contested. Historians such as Rolena Adorno, Patrick Charles Pautz, and Andrés Reséndez have placed him at the heart of debates on early Indigenous–European encounters, captivity, and proto-ethnography. Yet outside academic circles, he remains overshadowed by the dominant Anglo-American narrative of the frontier.

Part of this marginal position has to do with the kind of figure Cabeza de Vaca became. He was neither a successful conquistador nor a founder of colonial institutions, and thus did not fit easily into the political or ideological stories that later shaped U.S. national identity. His trajectory—marked by captivity, forced adaptation, and uneasy coexistence within multiple Indigenous worlds—did not lend itself to the heroic model promoted in popular accounts of exploration.

Historiographically, his reception has evolved. At the end of the nineteenth century, Charles Fletcher Lummis celebrated him as “the first American traveler,” emphasizing the extraordinary journey he undertook half a century before Anglo settlement reached these lands. Later, the foundational volume Spanish Explorers in the Southern United States, 1528–1543—first published in 1907 and reissued by the Smithsonian Institution in 1935—placed Naufragios alongside other essential early accounts and reinforced its value as a primary source. More recent scholarship—such as Andrés Reséndez’s A Land So Strange (2007)—has expanded this perspective, situating Cabeza de Vaca within the broader study of Indigenous–European interaction, cross-cultural mediation, and the limits of imperial power on the North American frontier.

As with Francisco de Saavedra—another Spaniard whose role I have previously discussed—Cabeza de Vaca remains far from central in the broader American historical imagination. Yet his story helps widen our view of the country’s origins: not because he stood at their center, but because his experience reveals forms of Indigenous–Spanish interaction later overshadowed by the dominant Anglo narrative.

Title page: La relacion y comentarios del gouerna, 1555. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Conclusion

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca embodies a different kind of explorer—not the victorious conqueror, but the survivor who learns and observes. His account is the first Spanish chronicle of Texas and an irreplaceable window into the Indigenous world of the sixteenth century.

Recovering his memory is not an antiquarian gesture, but a way of recognizing that the history of the United States was, from its beginnings, plural, mixed, and shaped by cultural encounters that still echo today in debates about frontier and identity, as well as in broader discussions about intercultural contact and historical memory in the early Americas—conversations that continue to shape how we narrate the origins of the U.S. Southwest.

His voice—overshadowed in Texas and in the broader national memory—deserves to be heard again, not as a relic but as a living part of American history. It is also a reminder that the “frontier myth” of Anglo conquest, perpetuated for decades by Hollywood and popular culture, is only one version of the story—and that Cabeza de Vaca’s survival reveals another: a frontier of adaptation, exchange, and fragile coexistence.

José A. Adrián is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Málaga (Spain), specializing in language as a cognitive phenomenon and in its oral and written disorders. In addition to his academic work, he maintains a strong interest in history and the role of Spain in the Americas.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.