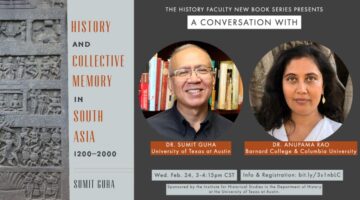

The History Faculty New Book Series presents: History and Collective Memory in South Asia, 1200–2000(University of Washington Press, 2019) A book talk and discussion withSUMIT GUHAProfessor of HistoryThe University of Texas at Austinhttps://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/profile.php?eid=sg7967 With discussant:ANUPAMA RAOTOW Associate Professor of History,Barnard College and Columbia Universityhttps://history.barnard.edu/profiles/anupama-rao In this far-ranging and erudite exploration of the South Asian past, […]