In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

…Soy ese amor que negarás para salvar tu dignidad

Soy lo prohibido…

(Roberto Cantoral, 1970)

The first time I engaged with the work of Dr. Zeb Tortorici was in 2019, at the end of a Texas fall when the idea of a worldwide emergency as COVID-19 seemed improbable, if not impossible. At the time, I was meeting with my future PhD advisor, Dr. Laura Gutierrez, at UT Austin, to explore research into queer disgust, the performance of pleasure, excess, and queer rejection to LGBTT+ hegemony in México. Dr. Gutierrez told me about a book she considered helpful for my research. The book was Sins Against Nature: Sex and Archives in Colonial New Spain (2018). This book would become my introduction to the work of Dr. Tortorici, his affective approach to archived documentation, and the methodological shift to queering archives in the search for possibilities for censured queer alterity.

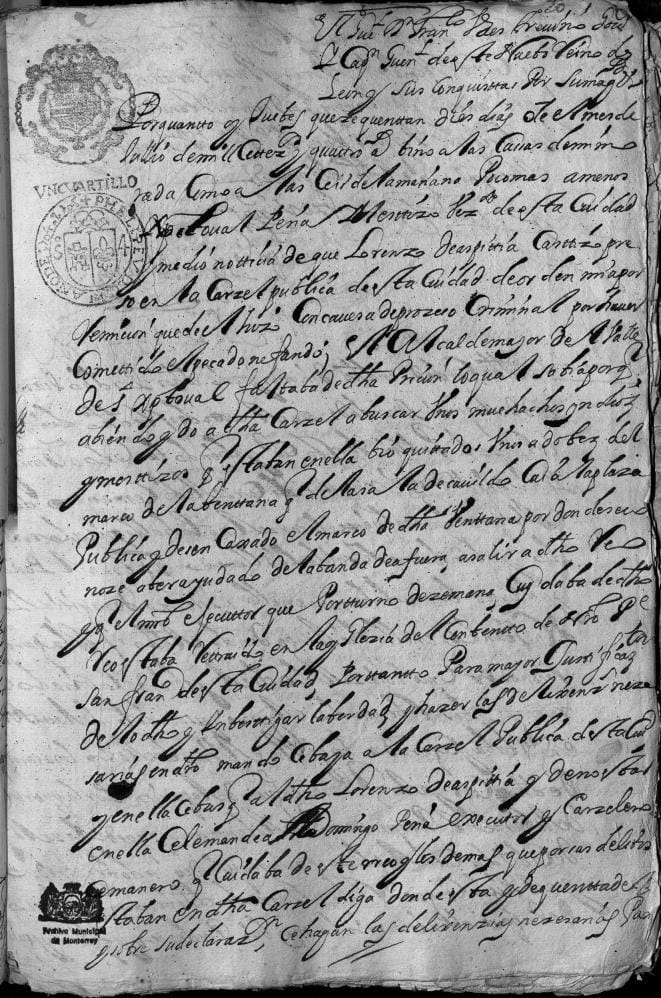

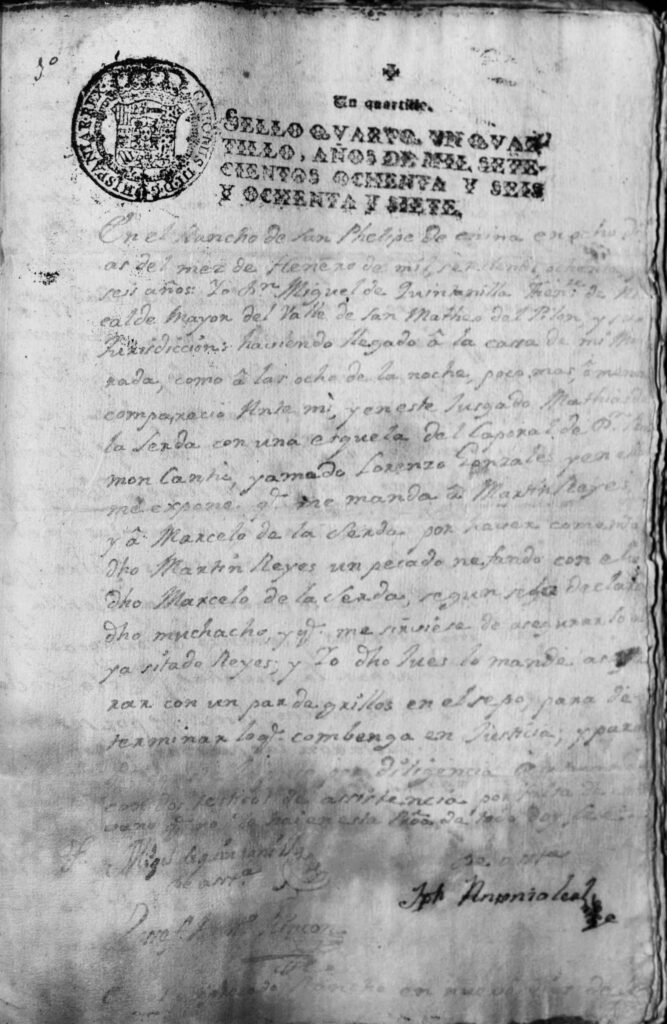

Once I had the book in my hands, I examined it with care and attention. A medium-sized book, not too heavy, yet not insubstantial. A black and red cover showcased an image of what looked to be a winged devil speaking to various demonic creatures. Navigating the book’s pages was as fascinating as exploring the aesthetic composition of its exterior. Dr. Tortorici introduces the book by re-telling an event from my hometown, Monterrey, in 1656. Lorenzo Vidales, a local thirteen-year-old, was found engaging in bestiality with a goat, an act the civilian and religious courts punished by having Lorenzo whipped and expelled from the city of Monterrey. The death penalty served as a warning and promise for him if he ever thought of returning to the city. Even when the event belongs to the municipal archives of Monterrey and, therefore, to our national and regional historical memory, it is, in no way, part of the collective knowledge of those of us who grew up at La Sultana del Norte, as Monterrey is known. It was too repulsive, too nefarious; and simply too deviant to have a place in the official narrative of the city, a space constructed around industrial myths where the will and determination of the industrial catholic bourgeoise made the desert fertile.

Having the opportunity to speak to Dr. Tortorici in person shortly after encountering his work doubled my excitement and curiosity about his research into excess and memory. The start of that conversation, which I hope to continue over the years, was marked by what I felt to be a meeting of kindred spirits of a sort who haunt archived excess and academic curiosity. These spirits surely welcome gracious archival accidents. So are the questions and conceptual possibilities that archival accidents allow. What I found most valuable, however, as I venture into my own research on the possibilities of excess in performance art in Monterrey, were the questions of embodied viscerality and excess, and its trans-temporal archival presence.

Dr. Tortorici’s research has a particular connection to my own work on the visceral and excess and to my analysis of queer possibilities in the face of hegemonic normalcy. For context, two special issues of A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies (to which Dr. Tortorici contributed) give theoretical weight to embodied and archival vicerality by defining it as “a phenomenological index for the logics of desire, consumption, disgust, health, disease, belonging, and displacement that are implicit in colonial and postcolonial relations.”[1] Tortorici’s contribution adopts a microhistorical lens to show how vicerality can structure and baffle archival impulses. Incidents of necrophilia, fellatio, masturbation, and erotic religious visions from colonial Mexican archives reveal the layered and complex “gut feelings” of historical actors – including the archivists and historians who registered these events.[2] In short, although Dr. Tortorici’s work covers an earlier period than my scholarly interests, I was eager to engage in dialogue with him—especially when it comes time to sort out affective approaches that queer the archives and confront the excessive elements that have been intentionally overlooked.

Let me zoom out briefly from my first reading of Sins Against Nature and my exciting first conversation with Dr. Tortorici about our shared research interests, to offer a brief overview of his research trajectory. From there, we can begin to explore how his understanding and work with the archives of “No” are opening up archival possibilities for radical alterities to institutional respectability. By archives of “No”, I refer to that which is too excessive to be archived, or even remembered by institutions; therefore rejected on a “anti” archive category, a “No” category .

Dr. Tortorici is an Associate Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Languages and Literature at New York University. His research interests center around queer colonial history and archives in Latin America, with particular attention to pornography, dissident sexualities, pleasure, desire, and censorship. In addition to several prestigious fellowships and visiting professorships, Dr. Tortorici also has a remarkable publication record. Sins Against Nature won the John Boswell Award from the Committee on LGBT History and the Alan Bray Memorial Book Prize. Dr. Tortorici’s work recognizes the value of intellectual community building for advancing valuable scholarly projects. This includes his co-editing different volumes on Ethno-Pornography, Centering Animals in History, Trans*historicities, and Medical reproductive knowledge in 18th-century Latin America.

Dr. Tortorici’s work in many ways represents a navigation of the archives of the “No.” As a historian of the “No”, his focus and methodology have centered on looking for different moments of non-history, non-citizens, and undesirable non-humans.[3] He hopes to guide academic curiosity toward that which has been historically silenced and those who have been double censured by the creators and the user-researchers of archives. A methodological turn toward the “No” should not be understood within the limits of orthodox archival order and logic but rather as queer interruptions to academic normalcy. His approach to queering the archives is not reserved solely for diverse expressions of gender and sexuality. The implications of his questions around archival materials productively open broader alterities to the colonial order, which, in turn, make the “nefarious” episodes of the “no” histories he reconstructs transcendental.

Perhaps somewhat ironically, “pleasure,” despite the positive affect it connotes, nevertheless overlaps with the realm of the “No.” I’m fascinated by Dr. Tortorici’s work on pleasure for presenting a platform to speak of something that has been purposefully ignored, surveilled, and exoticized, and as a response to imposed contemporary archival respectability. Dr. Tortorici’s research opens a space for queer pleasure, embodied desires, and the erotic. His efforts are even more admirable precisely because they must work against the structural limits imposed by institutions holding archival traces of these pleasurable moments.

The good news is that visceral rejections of queer pleasure hold the key that can free over-silenced stories. Queer embodied conversations with archived pasts must be understood primarily as that: conversations. Dr. Tortorici leads us towards these conversations, which must necessarily turn towards careful coded dialogues that those queering archival research can affectively understand. These embodied visceral conversations inherently involve provocations, consumptions, and reactions. In this sense, Dr. Tortorici reveals how queering colonial archives means showing how archives hold and censure stories of consumption that have provoked disgust within those who created the archive. These visceral tensions open a “beyond time” affective encounter with those who study and translate queer codes of the archive and engage in visceral dialogues with the present, past, and future. Dr. Tortorici is careful to point out the need for accurate translations of queer viscerality. The provocation censured, persecuted, and archived during the colonial period does not have the same affective meaning for contemporary audiences. These conversations, therefore, are very much in the translation.

I keep returning to a term Dr. Tortorici brought into our dialogue: imagination. In order to affectively navigate and queer the archives there is a need for radical imagination. Radical imaginaries permit deeper explorations of the “what if?” These historical possibilities, in turn, contribute to queer contemporary life beyond utopia. In this sense, Dr. Tortorici’s radical imaginaries regarding the archive contribute to a greater genealogy of academic shifts toward radical archival work. I am thinking here of Black feminist scholars such as Saidiya Hartman, Tina Campt, and Riley Snorton, who have opened up radical affective possibilities for queer archives of color.

Dr. Tortorici was featured in the panel “Histories of Collecting and Collecting Stories” for the 2022 Lozano Long Conference, titled “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives.” It is my sincere hope that this introduction may help situate his work as it continues to expand discussions of radical queer archival alterities.

Cuir norteño from Monterrey (México), member of the House of Majesty. PhD student at the Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies. Currently, he’s a Student Resident at CIESAS Noreste (Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social). He is interested in the possibilities for cuir radical futurity-building via excess, cuir rejection, and alternatives to hegemonic LGBTT+ respectability. He is the father of Carmela, a calico cat.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

[1] Sharon P. Holland, Marcia Ochoa, Kyla Wazana Tompkins; On the Visceral. GLQ 1 October 2014; 20 (4): 391–406. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2721339

[2] Zeb Tortorici; Visceral Archives of the Body: Consuming the Dead, Digesting the Divine. GLQ 1 October 2014; 20 (4): 407–437. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2721375

[3] For the history of the “no,” I am referring here to the work of “unthinkable” histories like those examined by Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1995) Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History.

Bibliography

Collections, F. L. (2017). Fales Video Archive . Obtenido de Sex in the Archives: Seeking Sex, Procuring Porn: https://vimeopro.com/nyutv/fales-library/video/208568051

Tortorici, Z. (2014). Visceral Archives of the Body: Consuming the Dead, Digesting the Divine. GLQ A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 20(4), 407-437.

Tortorici, Z. (2018). Sins Against Nature: Sex & Archives in Colonial News Spain. Duke University Press.

University, N. Y. (s.f.). Zeb Tortorici. Obtenido de https://as.nyu.edu/faculty/zeb-joseph-tortorici.html