During the Second World War, the United States and the Soviet Union formed a powerful partnership to defeat Nazi Germany. Their alliance did not, however, extend to a shared vision of the postwar world order. While U.S. leaders envisioned an open global economic system that would assure American access to markets and resources around the world, leaders in Moscow wanted to clamp down on parts of Europe and Asia in order to prevent the reemergence of hostile nations along the Soviet Union’s borders. In the closing phases of the war and especially in the first tumultuous months following the end of the fighting, U.S. and Soviet leaders increasingly clashed over a range of issues, especially the status of eastern Germany, Poland, and other parts of eastern Europe. The prospect of a new and dangerous geopolitical rivalry so soon after ending the fascist threat caused anger and anxiety among American leaders, who struggled to understand Soviet motives.

In February 1946, officials in Washington asked the U.S. embassy in Moscow why the Soviet government was failing to cooperate with American plans for the postwar international order. On the receiving end was George Kennan, a career foreign service officer who had risen to be the second-ranking American official in Moscow. Kennan replied with an extraordinary 5,300-word cable later dubbed the “long telegram.” Kennan drew on his long experience in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to lay out a distinctive view of Russian history and culture. You can read excerpts of his message below:

At bottom of Kremlin’s neurotic view of world affairs is traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity. Originally, this was insecurity of a peaceful agricultural people trying to live on vast exposed plain in neighborhood of fierce nomadic peoples. To this was added, as Russia came into contact with economically advanced West, fear of more competent, more powerful, more highly organized societies in that area. But this latter type of insecurity was one which afflicted rather Russian rulers than Russian people; for Russian rulers have invariably sensed that their rule was relatively archaic in form, fragile and artificial in its psychological foundation, unable to stand comparison or contact with political systems of Western countries. For this reason they have always feared foreign penetration, feared direct contact between Western world and their own, feared what would happen if Russians learned truth about world without or if foreigners learned truth about world within. And they have learned to seek security only in patient but deadly struggle for total destruction of rival power, never in compacts and compromises with it.

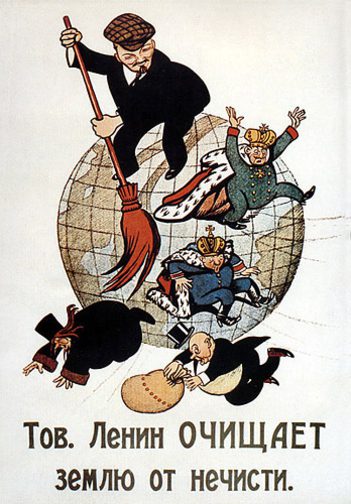

Soviet poster “Comrade Lenin cleans the Earth from scum”, November 1920 (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

It was no coincidence that Marxism, which had smoldered ineffectively for half a century in Western Europe, caught hold and blazed for first time in Russia. Only in this land which had never known a friendly neighbor or indeed any tolerant equilibrium of separate powers, either internal or international, could a doctrine thrive which viewed economic conflicts of society as insoluble by peaceful means. After establishment of Bolshevist regime, Marxist dogma, rendered even more truculent and intolerant by Lenin’s interpretation, became a perfect vehicle for sense of insecurity with which Bolsheviks, even more than previous Russian rulers, were afflicted. In this dogma, with its basic altruism of purpose, they found justification for their instinctive fear of outside world, for the dictatorship without which they did not know how to rule, for cruelties they did not dare not to inflict, for sacrifice they felt bound to demand. In the name of Marxism they sacrificed every single ethical value in their methods and tactics. Today they cannot dispense with it. It is fig leaf of their moral and intellectual respectability….

In summary, we have here a political force committed fanatically to the belief that with US there can be no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted, our traditional way of life be destroyed, the international authority of our state be broken, if Soviet power is to be secure. This political force has complete power of disposition over energies of one of world’s greatest peoples and resources of world’s richest national territory, and is borne along by deep and powerful currents of Russian nationalism. In addition, it has an elaborate and far flung apparatus for exertion of its influence in other countries, an apparatus of amazing flexibility and versatility, managed by people whose experience and skill in underground methods are presumably without parallel in history. Finally, it is seemingly inaccessible to considerations of reality in its basic reactions. For it, the vast fund of objective fact about human society is not, as with us, the measure against which outlook is constantly being tested and re-formed, but a grab bag from which individual items are selected arbitrarily and tendenciously to bolster an outlook already preconceived. This is admittedly not a pleasant picture. Problem of how to cope with this force [is] undoubtedly greatest task our diplomacy has ever faced and probably greatest it will ever have to face…. I cannot attempt to suggest all answers here. But I would like to record my conviction that problem is within our power to solve – and that without recourse to any general military conflict. And in support of this conviction there are certain observations of a more encouraging nature I should like to make:

(1) Soviet power, unlike that of Hitlerite Germany, is neither schematic nor adventurist. It does not work by fixed plans. It does not take unnecessary risks. Impervious to logic of reason, and it is highly sensitive to logic of force. For this reason it can easily withdraw – and usually does when strong resistance is encountered at any point. Thus, if the adversary has sufficient force and makes clear his readiness to use it, he rarely has to do so. If situations are properly handled there need be no prestige-engaging showdowns.

(2) Gauged against western world as a whole, Soviets are still by far the weaker force. Thus, their success will really depend on degree of cohesion, firmness and vigor which western world can muster. And this is factor which it is within our power to influence.

(3) Success of Soviet system, as form of internal power, is not yet finally proven. It has yet to be demonstrated that it can survive supreme test of successive transfer of power from one individual or group to another…. We here are convinced that never since termination of civil war have mass of Russian people been emotionally farther removed from doctrines of Communist Party than they are today. In Russia, party has now become a great and – for the moment – highly successful apparatus of dictatorial administration, but it has ceased to be a source of emotional inspiration. Thus, internal soundness and permanence of movement need not yet be regarded as assured.

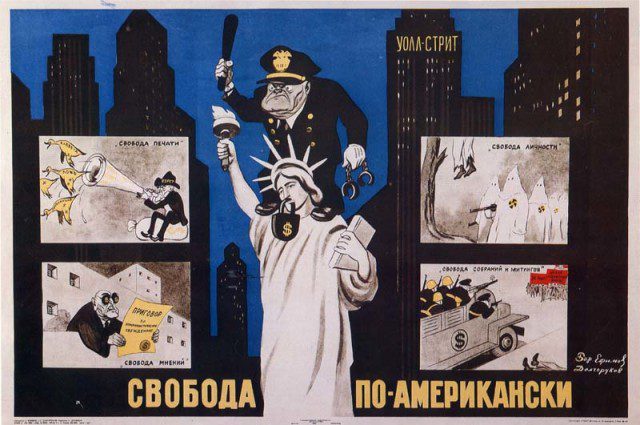

(4) All Soviet propaganda beyond Soviet security sphere is basically negative and destructive. It should therefore be relatively easy to combat it by any intelligent and really constructive program.

You may also like:

Mark A. Lawrence, The Global United States

Introduction to Mark A. Lawrence’s America in the World

Mark A. Lawrence on Not Even Past: “The Lessons of History,” “The Prisoner of Events in Vietnam,” “CIA Study [on the consequences of war in Vietnam]”

Jonathan C. Brown, “A Rare Phone Call from one President to Another”