By Ilan Palacios Avineri

In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

When Kirsten Weld writes of archives, her words feel pressing and urgent. She portrays repositories of historical materials as living entities. The documents and objects they house can be “neglected,” “ignored,” “confronted,” or “appreciated”— just like people. Societies can regard their records as basura (trash) or as precious bodies in desperate need of protection. Archives can also live multiple lives. They may serve as tools of state terror in one iteration or animate citizen activism in the next. They can victimize and heal. For Weld, like history, archives are not even past. Human beings breathe life into their contents, vivifying them and contesting them.

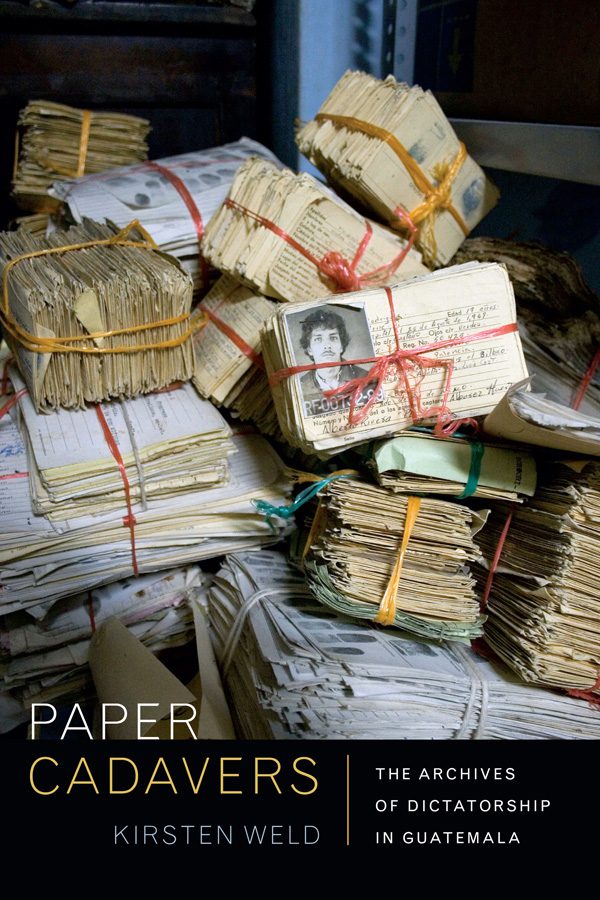

This conceptualization of archives becomes clear in Weld’s 2014 book, Paper Cadavers, which chronicles the discovery of Guatemala’s National Police Archives (AHPN). This repository, which is currently housed digitally at the Benson Latin American Library) contains chilling records of state repression, torture, and murder during the country’s 36-year-long civil war. Yet Weld refrains from focusing on the contents of these materials. Instead, she explores how Guatemalans grappled with the archives’ resurrection. She uncovers how they waged wars for decades to access these police documents amidst intimidation by the armed forces. She surveys how they sorted through the archives, as vermin scurried across the floor, to preserve rotting pages capable of legitimating claims state terror. Weld demonstrates how archives constitute “sites of social struggle” in addition to sources of data.

At the same time, Weld unveils how archives (re)awaken historical and political consciousness. She recounts how older workers at the AHPN—former guerrillas, trade unionists, community organizers, student activists — confronted documents detailing the violence committed against loved ones. She illuminates how these “paper cadavers” stirred trauma for many, including Esperanza who stumbled across a bundle of papers describing the discovery of two of her uncles’ corpses. The resurrection of such memories—from what Hannah Arendt called “holes of oblivion”—can be deeply painful. Weld elucidates how these older archivists remained steadfast, teaching younger workers how to process the often gruesome materials. This quotidian education helped fill gaps in the latter’s “spotty recollection of war,” transforming them into lifelong activists.

Throughout her book, Weld repeatedly underscores how archives, memories, and histories motivate their contemporaries. In a separate ongoing project on the Spanish Civil War in Latin America, she continues to address these themes, albeit with more distance from the present. In her 2019 article “The Other Door,” she explores how the Guatemalan left drew on historical narratives of the Second Spanish Republic to inspire their revolution between 1944 and 1954. Prominent politicians like Jacobo Árbenz and Juan José Arévalo praised the Second Spanish Republic’s expansion of democracy and land redistribution to advocate for similar reforms domestically. Enrique Muñoz Meany likewise stressed the need to “keep the memory of the [fallen] Spanish Republic . . . vivid and alive” to bolster his own government.

By contrast, Weld spotlights how Guatemala’s right-wing invoked alternative histories of the Second Spanish Republic to lambast the revolutionary leaders. Conservative newspaper columnists praised Francisco Franco’s “noble” and “chivalrous” regime for defending a supposed Spanish heritage from the Republican assault to advocate for a similar reconquest of Guatemala. Student leaders bolstered this narrative, casting Spain’s Republicans as “ferocious torturers” while excoriating Guatemala’s revolutionary leaders for granting them exile. Carlos Castillo Armas even reached out to Franco’s Spain to request moral support before carrying out his coup against Árbenz. By exposing these episodes, Weld unearths the afterlives of the Second Spanish Republic in Guatemala. She reveals how Guatemalans’ judgments of the recent past enlivened their activities in their present.

In her public history work, Weld also questions how historical actors engage or fail to engage elements of the past. In The Baffler, she describes how in the Trump era for example, political commentators in the US invoked the notion that “history will judge” the president’s actions. “[We] imagine that society will learn from past errors,” she writes, “as if human reason were an autonomous force.” However, as Weld’s work on Guatemala reminds us, there is no arc of history. Instead, people interpret the past in diverging ways. They can view an archive as a tool for social control or for social justice. They may understand political movements as noble fights for democracy or as profound moral recessions. History itself does “not judge, exonerate, or redeem,” Weld stresses. Instead, human beings construct and contest narratives, as well as the archives that help substantiate them.

Dr. Weld will contribute to the 2022 Lozano Long Conference. Her panel, entitled “(Re)conociendo community rights through archives and memory,” explores how different communities have pursued political rights by gathering documents and defending archives. The conference will be held in a hybrid format, allowing participants to attend regardless of their location. If you are interested in Weld’s aforementioned work, or in archival studies and memory studies, I would encourage you to attend.

Ilan Palacios Avineri is a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a historian of Central America, focusing on twentieth-century Guatemala. His research interests include militarization, state repression, surveillance, and the politics of natural disasters. Ilan holds a B.A. in History from Willamette University where he graduated cum laude in 2019. He received his M.A. in History from the University of Texas at Austin in 2021. His ongoing research focuses on the 1976 earthquake in Guatemala and the militarization of space, place, and daily life in Huehuetenango.

Banner image: Guatemalan National Police Historic Archive (AHPN).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.