We are very happy to announce a new online collaboration with our colleagues in the Department of History at the University of Exeter in the UK. Not Even Past and Exeter’s Imperial & Global Forum, edited by Marc Palen (UT PhD 2011) will be cross-posting articles, sharing podcasts, and sponsoring discussions of historical publications and events. We are launching our joint initiative this month with a blog based on a new book by two Exeter historians, Arguing About Empire: Imperial Rhetoric in Britain and France.

By Martin Thomas and Richard Toye

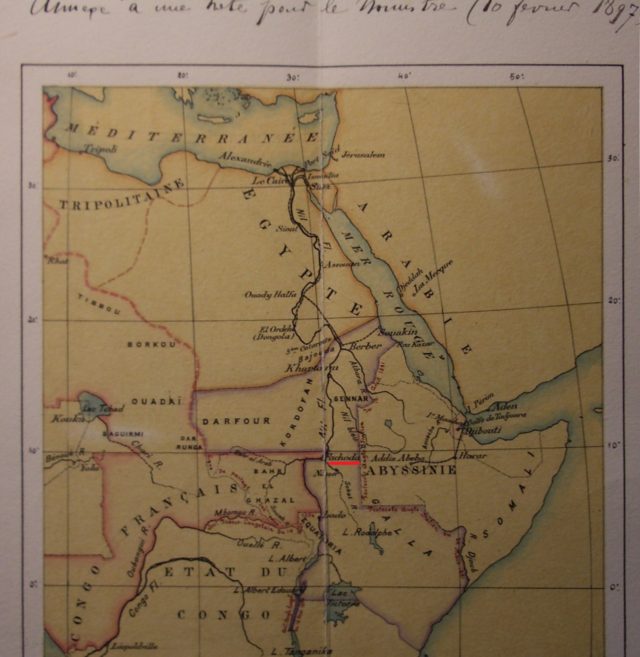

“At the present moment it is impossible to open a newspaper without finding an account of war, disturbance, the fear of war, diplomatic changes achieved or in prospect, in every quarter of the world,” noted an advertisement in The Times on May 20, 1898. “Under these circumstances it is absolutely essential for anyone who desires to follow the course of events to possess a thoroughly good atlas.” One of the selling points of the atlas in question – that published by The Times itself – was that it would allow its owner to follow “most minute details of the campaign on the Atbara, Fashoda, Uganda, the Italian-Abyssinian conflict &c.” The name Atbara would already have been quite familiar to readers, as the British had recently had a battle triumph there as part of the ongoing reconquest of the Sudan.

Fashoda, underlined in red, lay on the eastern margins of the Sudanese province of Bahr el-Ghazal. As this 1897 map indicates, the French Foreign Ministry, too, needed help in identifying Marchand’s location. (Source: MAE, 123CPCOM15: Commandant Marchand, 1895-98.)

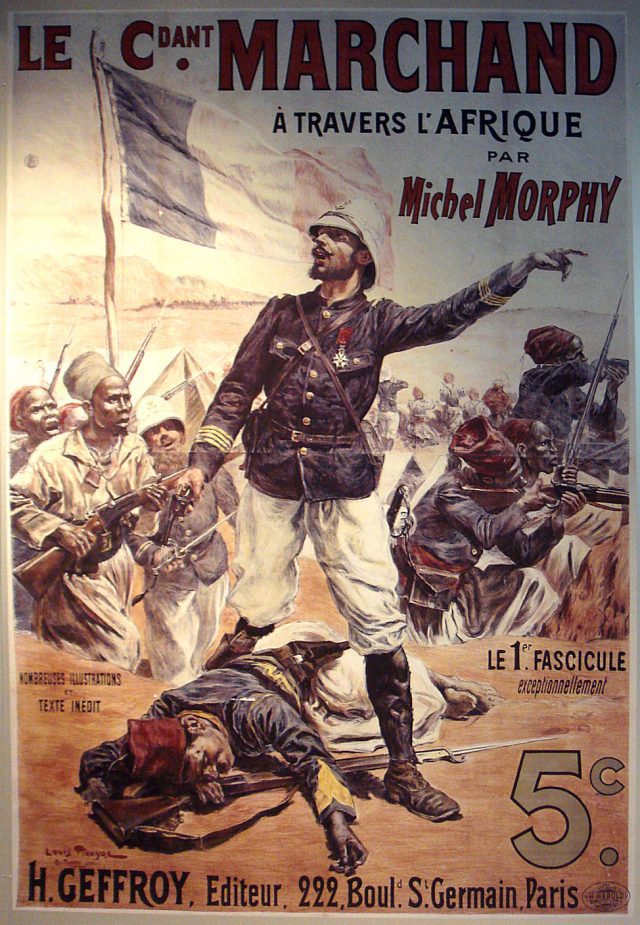

Fashoda, much further up the Nile, remained, for the time, more obscure. Newspaper readers might have been dimly aware that an expedition led by the French explorer Jean-Baptiste Marchand was attempting to reach the place via the Congo, but his fate remained a mystery. Within a few months, however, Captain Marchand and his successful effort to establish himself at Fashoda would be the hottest political topic, the subject of multitudes of speeches and articles on both sides of the English Channel as the British and French Empires collided, or at least scraped each other’s hulls. It never did come to “war,” but there was certainly sufficient “disturbance, fear of war and diplomatic changes achieved or in prospect” to justify a Times reader purchasing an atlas, perhaps even the half-morocco version, “very handsome, gilt edges,” that retailed at 26 shillings.

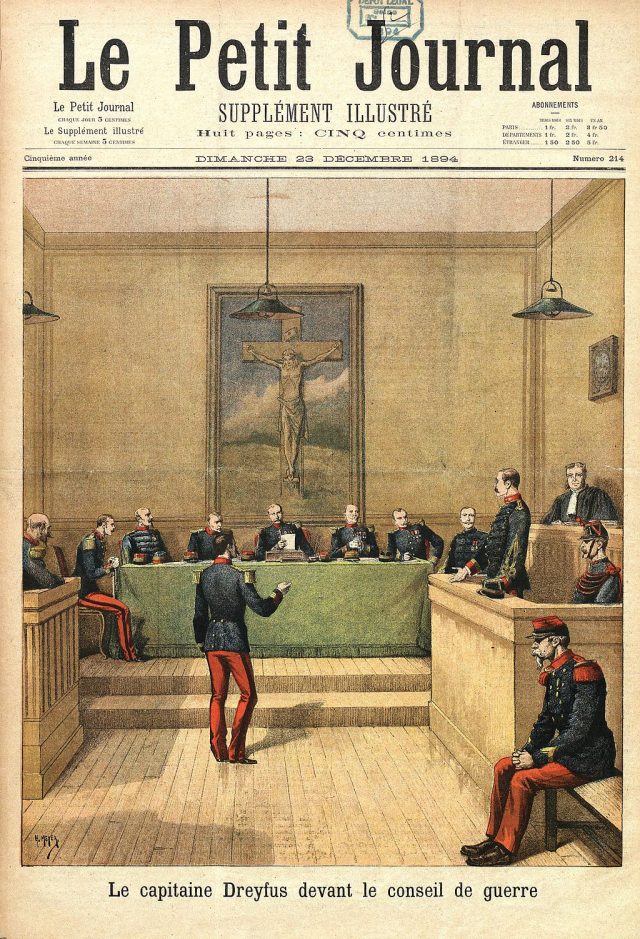

The clash at Fashoda was both a seminal moment in Anglo-French relations and a revealing one with respect to imperial language. In addition to rhetoric’s role in stoking up tensions, there are further angles to be considered. Falling at the height of the Dreyfus affair, in which a Jewish Army officer, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, endured a protracted retrial after being wrongly convicted of spying for Germany, British official readings of the Fashoda crisis were also conditioned by the growing conviction that the worst aspects of French political culture – an overweening state, an irresponsible military leadership, and an intrusive Catholic Church – were too apparent for comfort.

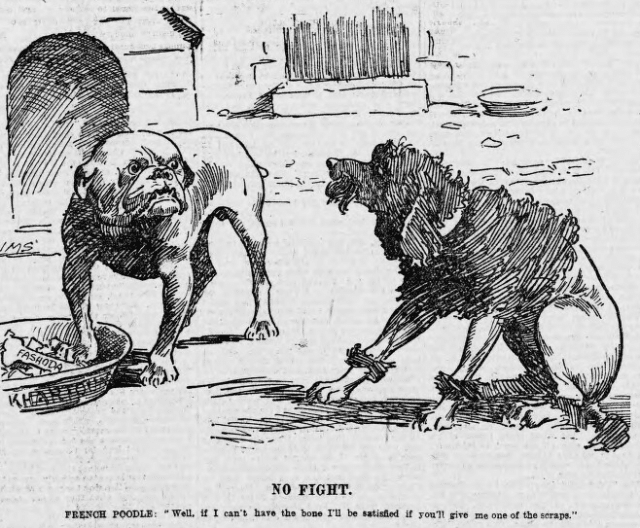

Viewed from the British perspective, dignity, above all, was at stake. The French were obsessed with the prospect of their own impending humiliation; whereas the British, from a position of strength, showed verbal concern for French amour propre, even while their own actions seemed guaranteed to dent it severely.

French Poodle to British Bulldog: “Well if I can’t have the bone I’ll be satisified if you’ll give me one of the scraps.” J. M. Staniforth, Evening Express (Wales).

What the rhetoricians of both countries had in common was their willingness to discuss the fate of the disputed area exclusively as a problem in their own relations, without the slightest reference to the possible wishes of the indigenous population. This is unsurprising, but there was more to the diplomatic grandstanding than appeared at first sight. It was the Dreyfus case that best illustrated how embittered French politics had become.

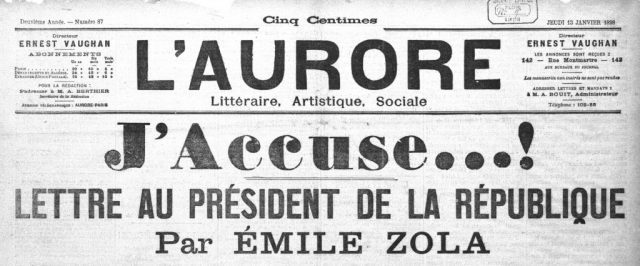

Dreyfus’s cause divided French society along several fault lines: institutional, ideological, religious, and juridical. By 1898 the issue was less about the officer’s innocence and more about the discredit (or humiliation) that would befall the Army and, to a lesser degree, the Catholic Church (notably imperialist institutions), were the original conspiracy against him revealed. So much so that the writer Emile Zola was twice convicted of libel over the course of the year after his fiery open letters in the new print voice of Radical-Socialism, L’Aurore in early 1898 compelled the Dreyfus case to be reopened,

Twelve months before Dreyfus was shipped back from Devil’s Island to be retried a safe distance from Paris at Rennes, Zola’s convictions confirmed that justice ran a poor second to elite self-interest.

High Command cover-ups, the ingrained anti-Semitism of the Catholic bishopric, and the grisly prison suicide on August 31 of Colonel Hubert Joseph Henry, the real traitor behind the original spying offense, brought French political culture to a new low. From the ashes would spring a new human rights lobby, the League of the Rights of Man (Ligue des droits de l’homme). Meanwhile, the Dreyfusard press, led since 1897 by the indomitable, if obsessive, L’Aurore, wrote feverishly of alleged coup plots to which Marchand, once he returned from Africa, might or might not be enlisted.

Charles Léandre, Caricature of Henri Brisson, Le Rire, November 5, 1898. Here caricatured as a Freemason.

At the start of November, Henri Brisson’s fledgling government finally decided to back down. A furious Marchand, who had arrived in Paris to report in person, was ordered to return and evacuate the mission. The right-wing press, fixated over the previous week on the likely composition of the new government and its consequent approach to the Dreyfus case, resumed its veneration of Marchand. La Croix went furthest, offering a pen portrait of Marchand’s entire family as an exemplar of nationalist rectitude. The inspiring, if sugary, narrative was, of course, a none-too-oblique way of criticizing the alleged patriotic deficiencies of the republican establishment and siding with the army as the institutional embodiment of an eternal (and by no means republican) France.

Something of a contrived crisis – or, at least, an avoidable one – Fashoda was also a Franco-British battle of words in which competing claims of imperial destiny, legal rights, ethical superiority, and gentility preserved in the face of provocation belied the local reality of yet more African territory seized by force. If the Sudanese were the forgotten victims in all this, the Fashoda crisis was patently unequal in Franco-British aspects as well.

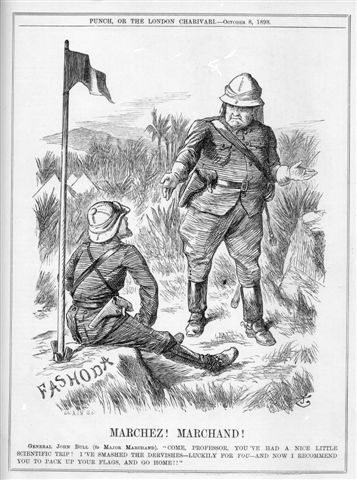

“Come Professor. You’ve had a nice little scientific trip! I’ve smashed the dervishes — luckily for you — and now I recommend you to pack up your flags and go home!” John Tenniel, Punch, Oct. 8, 1898.

On the imperial periphery, Marchand’s Mission was outnumbered and over-extended next to Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian expeditionary force. In London a self-confident Conservative government was able to exploit the internal fissures within French coalition administrations wrestling with the unending scandal of the Dreyfus case. Hence the imperative need for Ministers to be seen to be standing up in Marchand’s defense. In terms of political rhetoric, then, the French side of the Fashoda crisis was conditioned by official efforts to narrow the country’s deep internal divisions in the same way that the Republic’s opponents in politics, in the press, and on the streets sought to widen them.

![]()

Martin Thomas and Richard Toye, Arguing about Empire: Imperial Rhetoric in Britain and France

![]()

Read more about European Empires in the nineteenth century:

Edward Berenson, Heroes of Empire: Charismatic Men and the Conquest of Empire (2012). A vivid and captivating study, which locates fin de siècle constructions of heroism, sacrifice, and patriotic duty within the context of imperialist chauvinism.

William Irvine, Between Justice and Politics: The Ligue des Droits de l’Homme (2006). The go-to resource for insights into the concerns – and the colonial blind-spots – of France’s primary human rights lobby from the late nineteenth century onward.

Jennifer Pitts, A Turn to Empire: The Rise of Liberal Imperialism in Britain and France (2009). A landmark book that dissects the presumptive distinctions, and actual connections, between liberal thinking and support for imperial conquests in the long nineteenth century.

Michael Rosen, The Disappearance of Emile Zola: Love, Literature and the Dreyfus Case (2017). A beautifully written account of Emile Zola’s brief “exile” in Britain at the height of the Dreyfus Case; as much a story of the cultural misperceptions between Britain and France at the dawn of the twentieth century as an account of France’s leading Dreyfusard intellectual.

Bertrand Taithe, The Killer Trail: A Colonial Scandal in the Heart of Africa (2009). A deeply disturbing but essential account of the so-called Voulet-Chanoine mission, an appallingly cruel Frenchh imperial venture into West-Central Africa that, in all its butchery and madness formed the dystopian counterpart to Fashoda’s Sudan incursion.

Podcast: In Our Time: The Dreyfus Affair: Host Melvyn Bragg speaks with historians Robert Gildea, Ruth Harris, and Robert Tombs.

![]()

All images in public domain unless otherwise indicated.