By Betsy Frederick-Rothwell

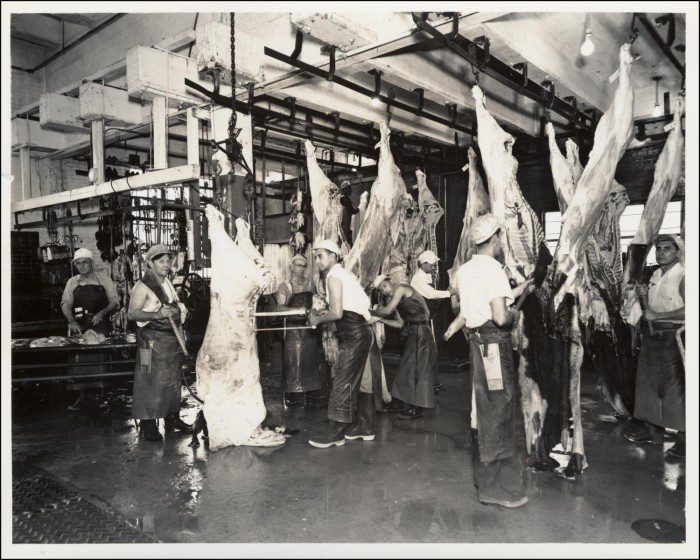

In late October 1939 a photographer from the Bureau of Identification spent the day among both warm and chilled beef carcasses, shrouded sides of pork, and racks of washed and dried offal, documenting the daily activities of the Austin Municipal Abattoir. The building’s foreign name (abattoir is French for slaughterhouse) and the photographer’s dramatic black and white images obscure the rather prosaic purpose of the documentation effort. The photographs illustrated not a volume of contemporary art, but rather an annual report written by the superintendent of the city-owned slaughterhouse for the City of Austin council members, informing the city managers of monthly revenues, recent building improvements, and new markets for slaughter by-products. A formal report such as this, with detailed operational descriptions and illustrations, was probably necessary because the city council members likely would not have visited the abattoir—then located at Pleasant Valley and East Fifth Street—in the regular course of business in the same way they may have toured the earlier-built public library or even the soon-to-be-completed Tom Miller Dam. Although the abattoir was a signal of Austin’s “modernity,” and its operation was critical to a hygienic life in Austin, most residents likely preferred that it be out of sight.

While a municipally funded and operated slaughterhouse may seem strange to Austin residents today, the city abattoir was a common feature of many urban centers in the early twentieth century. The French term for the facilities implies their origins in the large cities of Europe, but the widespread construction of city-owned slaughterhouses in American cities was a response to the exclusion of domestic slaughterhouse inspection in the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. The statue only required federal inspection of meat intended for interstate or foreign trade; for meat produced in slaughterhouses intended for sale within the city or the state, inspection was not required. The city abattoir, where inspection of meat for local markets could be assured, was proposed as a remedy.

Austin’s Municipal Abattoir as it appeared in 1939 (Photo Credit: PICA 00609, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

A bond issue passed in 1929 funded the Austin Municipal Abattoir’s 1931 construction as a concrete-frame building with brick and hollow-tile infill. The building’s legislated purpose, easily sanitized construction materials, and highly controlled inspection, slaughter, and rendering processes conjure a narrative common to almost all cities in the United States that wished to be “modern” and hygienic. The plant’s highly standardized workflow as described in the 1939 report gives a sense of why many radical writers at the time presented the modern slaughterhouse (or more pointedly the slaughter “factory”) as another step in the march toward the technological control of nature. Area ranchers bringing their animals to the Austin Municipal Abattoir for slaughter surrendered their yield not to an individual butcher but rather to an Abattoir intake clerk, who issued the rancher a “slaughtering ticket” that would eventually be exchanged for the finished product, a processed carcass with the adequate number of inspection stamps to make it acceptable for delivery to markets in Austin and surrounding small towns. The work of the Austin Abattoir was executed in carefully defined steps to increase operational efficiency. According to the abattoir’s annual report, in 1938 alone, the seventeen employees of the Austin Abattoir responsible for inspection, killing, butchering, washing, and chilling processed 22,975 cattle, 6,825 hogs, and 1,239 sheep and goats, with similar numbers adding up for 1939.

Bureau of Identification image of the Austin Abattoir’s slaughter room, October 1939 (Photo Credit: University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library, Austin, Texas)

The building’s relatively late construction date and location within the city evoke a story particular to Austin at the beginning of the twentieth century. The City of Austin considered sponsoring a municipal abattoir as early as 1913, and Paris, Texas, a town somewhat smaller than Austin, was the first city in the United States to build a city-owned slaughterhouse in 1909. However, heavy municipal debt resulting from the construction of the Austin Dam limited funds for other citywide improvements until the late 1920s, when an official city plan for beautification and improvement was passed by the city council. That plan, passed in 1928, also served the purpose of instituting racial segregation on a citywide scale. African Americans, who prior to 1928 lived in neighborhoods throughout Austin, were refused city services in all locations except those neighborhoods east of current-day Interstate Highway 35. Not surprisingly, the city located the Austin Municipal Abattoir at the city boundary on the far east side of this segregated neighborhood. Although proximity to the primary railroad lines was certainly a factor in locating the facility at the city’s eastern limit, the plant’s location in a segregated neighborhood and its distance from downtown embodies contemporary city leaders’ desire to keep this necessary public utility “invisible” to the city’s most prominent residents. However, the plant would not have been easy for its immediate neighbors to ignore; anecdotal accounts from other cities with similar abattoirs tell of terrible smells emanating from such buildings.

The Austin Abattoir’s closing in 1969 represented yet another shift in city dwellers’ relationship to the meat they consumed on an ever increasing scale. Changes in meat distribution networks and widespread availability of in-home refrigeration made city support of a local processing and preservation plant seem less critical.

Research for this article is based in part on:

Eldred Perry, “City of Austin Municipal Abattoir – Annual Report for the year 1939,” Austin History Center, Austin, TX.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.