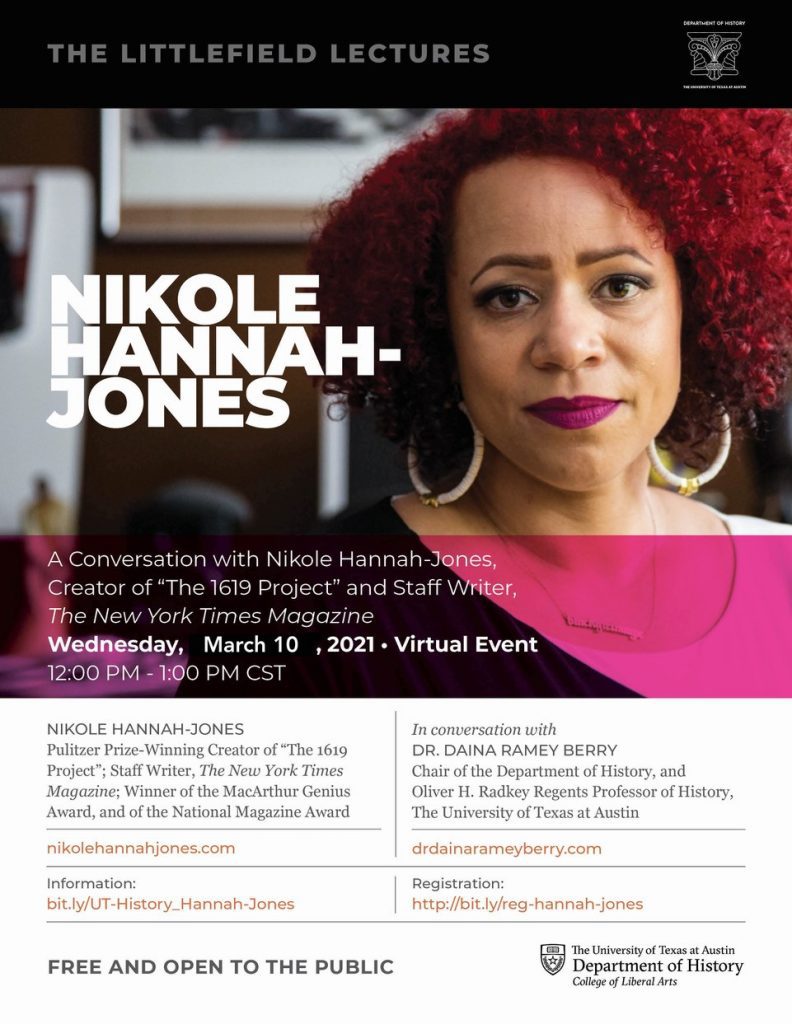

The Department of History’s Littlefield Lecture Series is pleased to host a conversation and moderated audience Q&A with Nikole Hannah-Jones.

NIKOLE HANNAH-JONES

Pulitzer Prize-Winning Creator of “The 1619 Project”;

Staff Writer, The New York Times Magazine;

Winner of the MacArthur Genius Award, and of the National Magazine Award

http://nikolehannahjones.com/

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/11/magazine/11nikole.html

in conversation with

DR. DAINA RAMEY BERRY

Chair of the Department of History, and Oliver H. Radkey Regents Professor of History

The University of Texas at Austin

http://www.drdainarameyberry.com/

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/db27553

Registration: http://bit.ly/reg-hannah-jonesWednesday, March 10. 12:00-1:00pm CST.

Online. Free and Open to the Public.

Hannah-Jones was awarded the MacArthur Genius Grant in 2017 for “reshaping national conversations around education reform.” This is but one honor in a growing list: She is the creator of the The New York Times Magazine’s “The 1619 Project,” about the history and lasting legacy of American slavery, for which her powerful introductory essay was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for commentary. She’s also won a Peabody, two George Polk awards, and the National Magazine Awards three times.

Hannah-Jones covers racial injustice for The New York Times Magazine, and has spent years chronicling the way official policy has created—and maintains—racial segregation in housing and schools. Her deeply personal reports on the Black experience in America offer a compelling case for greater equity. Hannah-Jones is the creator and lead writer of the New York Times’ major multimedia initiative, “The 1619 Project.” Named for the year the first enslaved Africans arrived in America, the project features an ongoing series of essays and art on the relationship between slavery and everything from social infrastructure and segregation, to music and sugar—all by Black American authors, activists, journalists, and more. Hannah-Jones wrote the project’s introductory essay, which ran under the powerful headline “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written. Black Americans Have Fought to Make Them True.” The essay earned Hannah-Jones her first Pulitzer Prize, for commentary. Random House has also announced it will be adapting the project into a graphic novel and four publications for young readers, while also releasing an extended version of the original publication, including more essays, fiction, and poetry.

Hannah-Jones has written extensively on the history of racism, school resegregation, and the disarray of hundreds of desegregation orders, as well as the decades-long failure of the federal government to enforce the landmark 1968 Fair Housing Act. She is currently writing a book on school segregation called The Problem We All Live With, to be published on the One World imprint of Penguin/Random House. Her piece “Worlds Apart” in The New York Times Magazine won the National Magazine Award for “journalism that illuminates issues of national importance” as well as the Hillman Prize for Magazine Journalism. In 2016, she was awarded a Peabody Award and George Polk Award for radio reporting for her This American Life story, “The Problem We All Live With.” She was named Journalist of the Year by the National Association of Black Journalists, and was also named to 2019’s The Root 100 as well as Essence’s Woke 100. Her reporting has also won Deadline Club Awards, Online Journalism Awards, the Sigma Delta Chi Award for Public Service, the Fred M. Hechinger Grand Prize for Distinguished Education Reporting, and the Emerson College President’s Award for Civic Leadership. In February 2020, she was profiled by Essence as part of their Black History Month series, celebrating “the accomplishments made by those in the past, as well as those paving the way for the future.”

Hannah-Jones co-founded the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting with the goal of increasing the number of reporters and editors of color. She holds a Master of Arts in Mass Communication from the University of North Carolina and earned her BA in History and African-American studies from the University of Notre Dame.

Please share widely with your interested colleagues and networks. Thank you.

For event questions or technical issues, please email: cmeador@austin.utexas.edu.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.