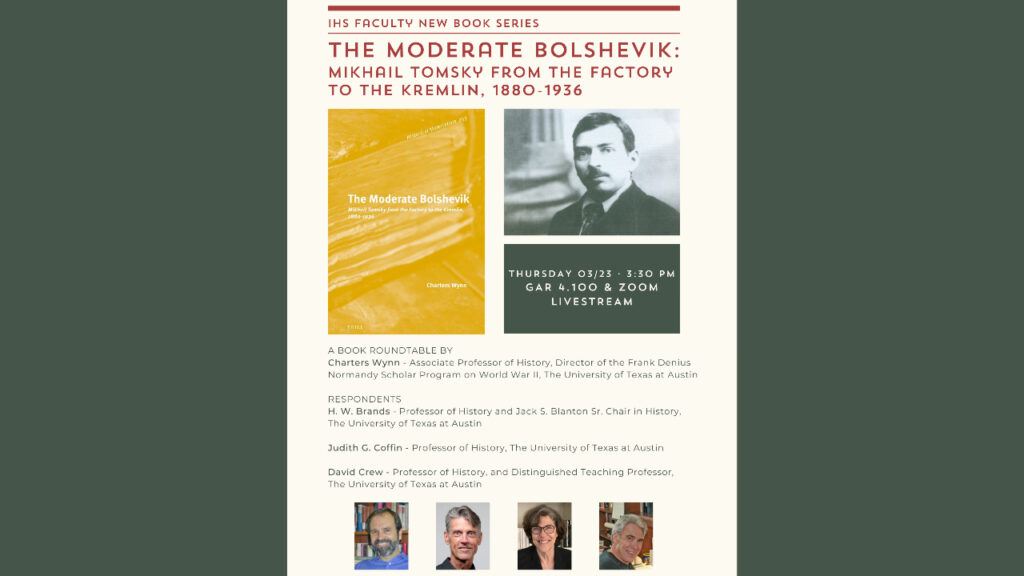

The Moderate Bolshevik: Mikhail Tomsky from The Factory to The Kremlin, 1880-1936

Brill Publishing (Hard Cover): 2022; and Haymarket Books (Paperback): May 2023

by Charters Wynn

This first English-language biography of Mikhail Tomsky reveals his central role in all the key developments in early Soviet history, including the stormy debates over the role of unions in the self-proclaimed workers’ state. Charters Wynn’s compelling account illuminates how the charismatic Tomsky rose from an impoverished working-class background and years of tsarist prison and Siberian exile to become both a Politburo member and the head of the trade unions, where he helped shape Soviet domestic and foreign policy along generally moderate lines throughout the 1920s. His failed attempt to block Stalin’s catastrophic adoption of forced collectivization would tragically make Tomsky a prime target in the Great Purges.

“This is an excellent, deeply researched, and well-written book that will be required reading for those interested in Soviet history and will be useful for others in labor history.”

—J. Arch Getty, The Russian Review

Dr. Charters Wynn is Associate Professor of History and Director of the Frank Denius Normandy Scholar Program on World War II at the University of Texas at Austin. The American Historical Association awarded his book, Workers, Strikes, and Pogroms: The Donbass-Dnepr Bend in Late Imperial Russia, 1870-1905 (Princeton University Press, 1992), the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize.

Discussants:

H. W. Brands

Professor of History and Jack S. Blanton Sr. Chair in History

The University of Texas at Austin

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/brandshw

Judith G. Coffin

Professor of History

The University of Texas at Austin

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/jcoffin

David Crew

Professor of History, and Distinguished Teaching Professor

The University of Texas at Austin

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/crewdf

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.