Amos Tutuola Odegbami was a Nigerian amateur novelist interested in promoting Yoruba culture to the outside world. Tutuola was born in 1920 at Wasimi, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. The young Amos had limited western education, stopping at high school level before moving to Lagos, Nigeria, in 1939 to learn smithing. He later joined the services of the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation (now Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria) where he retired in 1976.

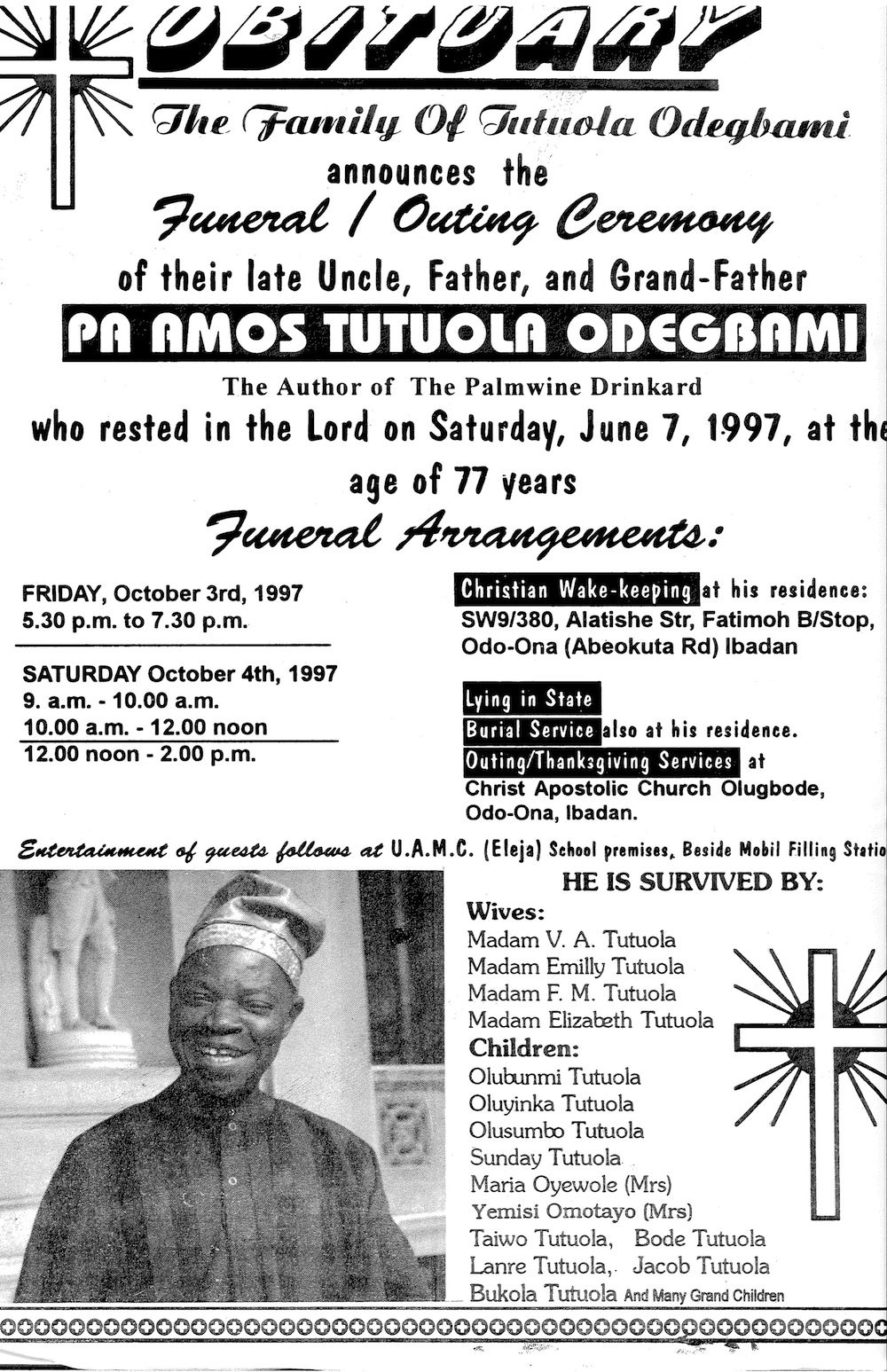

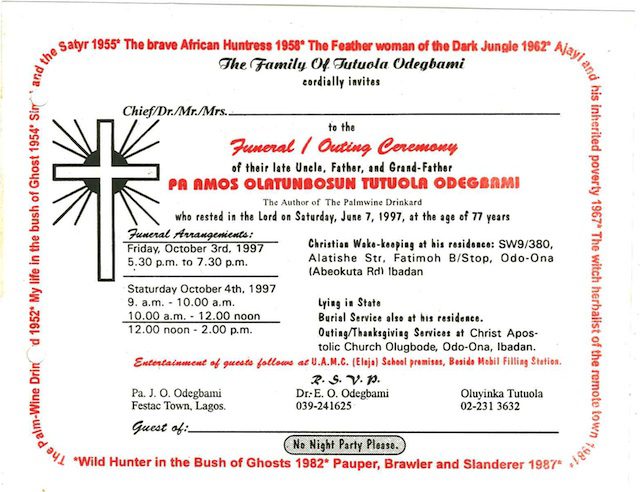

Tutuola’s prominence is tied to his writing career. Though with limited western education, he became a celebrated author both within and outside Nigeria. Some of the works to his credit include: The Palm Wine Drinkard (1952); My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1954); and Simbi and the Satyr of the Dark Jungle (1955). Amos Tutuola’s fame began with his first novel, The Palm Wine Drinkard. He was a member of the Association of Nigerian Authors and had an extensive network of relationships with friends and colleagues, which extended to the United States. One such friend was Dr. Ben Lindfors of the Department of English at The University of Texas at Austin. Amos Tutuola Odegbami died on Saturday, June 7, 1997. He was buried three months later on October 4, 1997 at his hometown Odo-Ona, Ibadan, Oyo State.

African burial ceremonies highlight the importance of valor, selflessness, and diligence (as well as other celebrated values) as everlasting motifs and prerequisites for good living. Indirectly, these values serve to emphasize the importance of traditional nobility and preservation of good name, honor, and service, which are fundamental for good leadership. It was only the good and the noble that were usually celebrated in burials. The cowardly and selfish were discarded in the ‘evil forest’ or buried without such fanfare. These burial practices were rooted in the past and were underpinned by the peoples’ indigenous religious beliefs. Although African traditional burial practices have been modified in the course of time, many still survive to date.

Examining the documents surrounding Tutuola’s burial (held at UT Austin’s Harry Ransom Center), one familiar with burial practices in Africa will be quick to notice that Tutuola was not accorded the kind of funeral one would expect a person with his popularity would be given. The inability to give the late Tutuola a deserving burial could be traced to financial constraints. The quality of Tutuola’s funeral brochure is very poor compared to what one would expect to see at the funeral of a person as famous as he was. The tributes, offered seem like afterthoughts. In addition, a newspaper report published the day after his funeral ceremony noted that Tutuola’s family had no support from the government or the publishers of his works in planning his funeral.

Fame and intellectual accomplishments in Nigeria in the 1990s did not equal wealth and power. During the period that Tutuola lived, Nigerian authors and academics were mostly poor. It was one thing to belong to a well-to-do class and another thing to be a known writer. Although he was a prolific and popular novelist, Tutuola was a poor author. So in death as in life, his funeral reflected his placement on the social ladder.

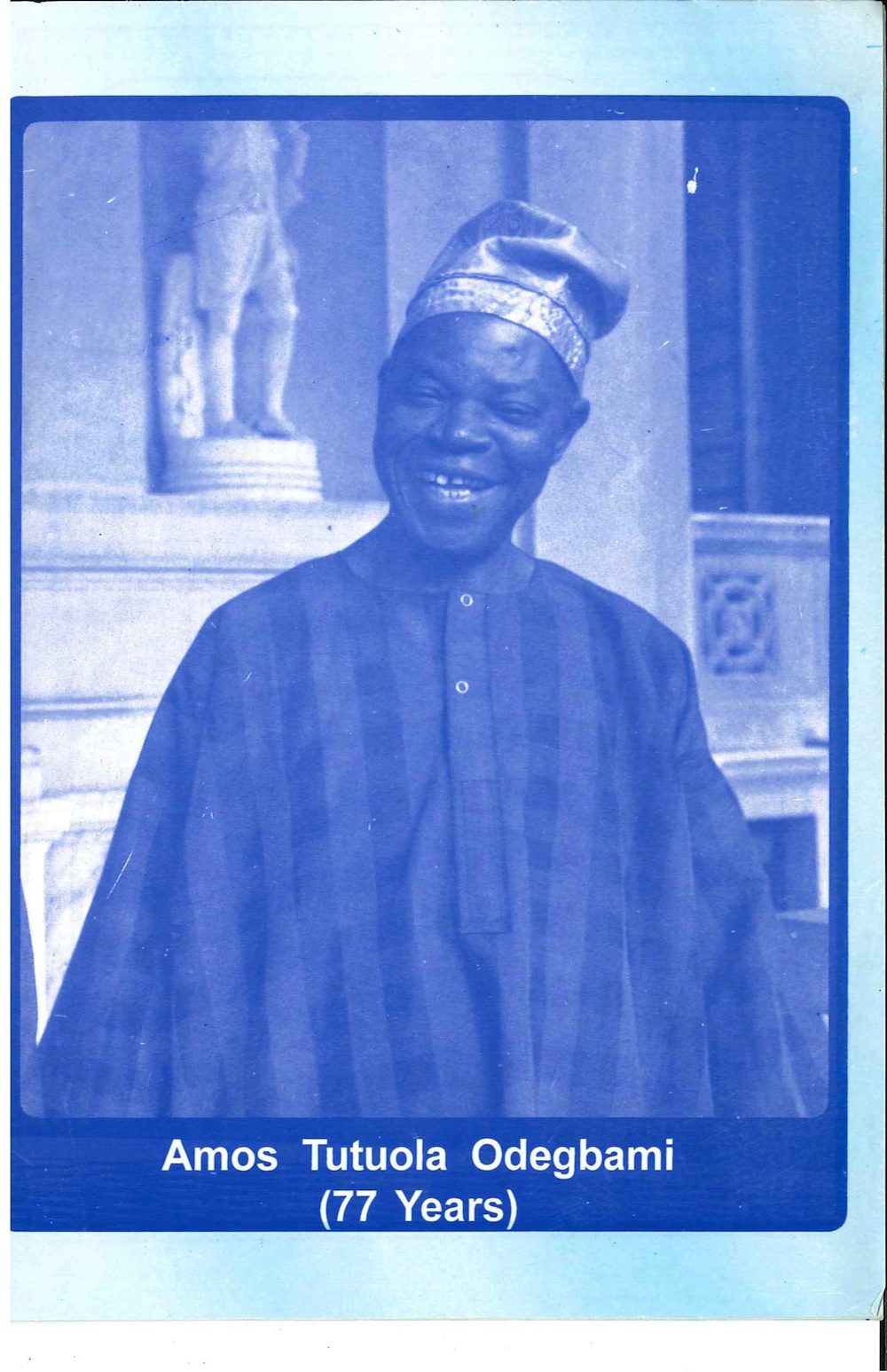

Tutuola’s funeral brochure emphasizes his interest in promoting Yoruba Studies but with significant limitations. Tutuola’s photo showing him adorned in traditional Yoruba attire was used as the front cover of the brochure. His biography and the tributes from his associates refer to his unrelenting commitment to the Yoruba. Even more striking is the language used in publishing the brochure. In Nigeria, depending on the social status of the deceased or his survivors, burial ceremonies could attract people from diverse ethnic groups. Therefore, funeral documents in post-colonial Nigeria were usually published in English if the family planned to give the deceased a Christian burial in a service conducted only in English or a combination of English and the indigenous language of the deceased. Although Tutuola’s biography, tributes, and the appreciation by the family were in English, the rest of the brochure was published in Yoruba.

Even more striking is the kind of funeral accorded Tutuola. The invitation card, newspaper reports on the proceedings of the burial, and the brochure show that Tutuola was given a Christian burial. Neither the funeral activities on the invitation card nor the brochure mentioned any Yoruba traditional burial practice for the late Tutuola. The absence of traditional Yoruba burial practices and other documents suggest that Tutuola was more of a Christian than a Yoruba traditionalist. In his autobiography, Tutuola ends the short history of his life by saying that he was a member of the African Church. But he says nothing about his commitment to Yoruba traditional religion.

Nothing in the funeral documents suggests they were fulfilling the will of the deceased. Africans give careful attention to fulfilling the wishes (especially last wishes before death) of a deceased. Family members do everything in their power to fulfill wishes left by their deceased loved ones. They believe that failure to meet those demands would hinder the deceased from having a smooth journey to the spirit world or possibly stop them from entirely joining their ancestors. It is also believed that not meeting the desires of the deceased could cause misfortune or even death for family members. Tutuola’s family would not have overlooked his wishes if he had any that related to the kind of burial he wanted to be given. One would have expected that Tutuola’s activism in promoting Yoruba culture would have made him want a traditional Yoruba burial.

Amos Tutuola’s activism in promoting Yoruba studies seems to have been more of an intellectual exercise than a desire for personally practicing traditional Yoruba culture. Neither his funeral brochure nor any other documents suggest that he took active part in the very culture he sought to promote.

All sources consulted and images used are courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. They are held in the following collections:

1. African Studies Collection, Tutuola, Amos. Articles and booklet re: Tutuola’s funeral 10.L.

2. African Studies Collection, folder 3.3, Lindfore, Tutuola’s Correspondence with BL, primarily, 1968-1997.

You may also like:

Mackenzie Finley’s article on the letters of Kenyan writer, Grace Ogot