On June 18th 1959, dressed in full army fatigues and accompanied by several comrades exhibiting an equally imposing revolutionary appearance, Che Guevara landed in Gaza. Considering his reputation today, one might have expected the 31-year-old Che to, perhaps, instruct the Palestinian resistance fighters (the Fedayeen) in the ways of guerrilla warfare, tell them in detail about his grand foco tactics, or take notes on their then-decade-long battle of resistance against Israel. Indeed, upon first learning of Che’s first – and only – visit to Gaza, I myself was filled with such questions. Was such an exchange of revolutionary tactics the legacy of his visit? Did he come there on purpose in order to build long-term relationship with Palestinian fighters? Was he attracted to Gaza as a hotbed of universal resistance to colonialism? What exactly came of this visit and who did he meet there? I was curious to know.

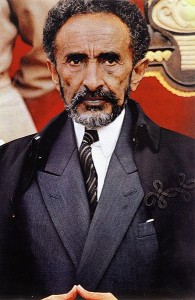

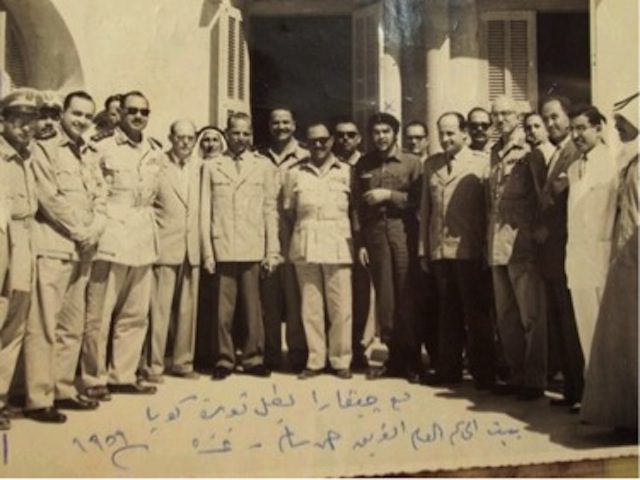

I first heard of Che’s intriguing visit about three years ago. The random person I met in the archives could not tell me much besides the fact that he read somewhere (but where?) that Che visited the Shati refugee camp and was warmly welcomed by its Palestinian inhabitants. That was not much. Searching the web yielded the image above which shows Che and other dignitaries with Ahmad Salim, the powerful Egyptian governor of Gaza. Che’s trustworthy biographer, Jon Lee Anderson, added a few more details and a date but nothing else. So, with this modest beginning, I ventured into the archive to find the story behind the visit and the photo. I started with the Israeli State Archives. From the end of the 1948 war until 1956, and again between 1957 and 1967 (when it was conquered by Israel during the Six Day War), Gaza was under Egyptian rule and their army controlled every aspect of Palestinian life, including their resistance to, and infiltration of, Israel. The Israeli State Archive seemed promising because of how closely they had monitored Gaza throughout this period and into the period of Israeli occupation. I thought that the Israelis could not possibly have missed such a high-profile visit by one of the chief theoreticians and practitioners of guerrilla warfare. To my surprise, it turned out they did. In fact, Che’s visit to Gaza left no impression whatsoever in the Israeli archives. Thus, in the absence of evidence from the Israeli archive and the absence altogether of an Egyptian archive, I turned to the Arab press. What I found was somewhat surprising. Che, it turned out, was a Cuban nobody that the Egyptians mostly ignored.

Indeed, as it turned out, Che’s visit to Egypt – then known as the United Arab Republic – was a brief, low-key event that was tightly controlled by Egyptian authorities reluctant to acknowledge competing revolutionary projects such as Cuba’s. His trip to Gaza was even further played down. The press contingent was kept to a minimum, no iconic photographs were published and – so it seems – only a single image survived. Though Che and the Cubans visited several refugee camps, by day’s end, they dined not with top leaders of the Palestinian revolutionary Fedayeen, but with the Brazilian contingent of the UN Emergency Force. In fact, not a single member of the Fedayeen was present, and there was no talk about revolutionary theory, neo-colonialism, Zionist imperialism, or any of the other 1960s sub-categories of global resistance. Twenty-four hours after Che arrived in Gaza, he was back in Cairo. The newspapers the next day buried the story.

Back in Cairo, the theme continued. The Cubans were far from the talk of the town, and Egyptian attention was visibly elsewhere with the more important visit of Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie. While Selassie received heavy press coverage, the Cubans, except for a few back-page reports, got hardly any. It was not that the Cubans were ignored. Though he was apparently too busy to officially greet Che in the airport upon his arrival, the following day, Nasser awarded him the United Arab Republic’s Decoration of the First Order in a quaint, sparsely-attended ceremony. The rest of the visit was characterized by a paternalistic tone, wherein the Egyptians lectured the inexperienced Cubans on methods of engendering an agricultural revolution in the interest of social equality, and various theories and suggestions were provided as to how the Cubans ought to approach the industrialization of their country. Thereafter, the Cubans left to Damascus, visited the tomb of Salah al-Din (Saladin), a renowned symbol of resistance and sacrifice, and continued on their journey to other locales in Africa and Asia.

This visit to the revolutionary heartland of the Arab world tells us in no uncertain terms that the bearded, cigar-smoking Che was not yet an international icon of global resistance and that that iconic revolutionary decade, the 1960s, had not yet truly begun. In fact, the point of his visit appears not so much to have been to launch an international revolutionary movement but to launch instead a three-month tour to the Third World so Che could introduce himself to the various countries’ progressive elites and, perhaps, along the way, forge commercial ties and hopefully sell some sugar. Yes, that’s right: sugar took precedence over guerilla warfare. But with this tour, Cuba also began a search for its revolutionary role in world affairs. Three years later, Che would emerge the universally recognizable Third World icon of the New Man, worthy of front-page coverage even in Egypt. Indeed, in his future meetings with Nasser, the tables were turned and Nasser presented himself as Che’s attentive and modest acolyte. By this point, of course, the global resistance culture of 1960s was already an integral part of daily Arab politics.

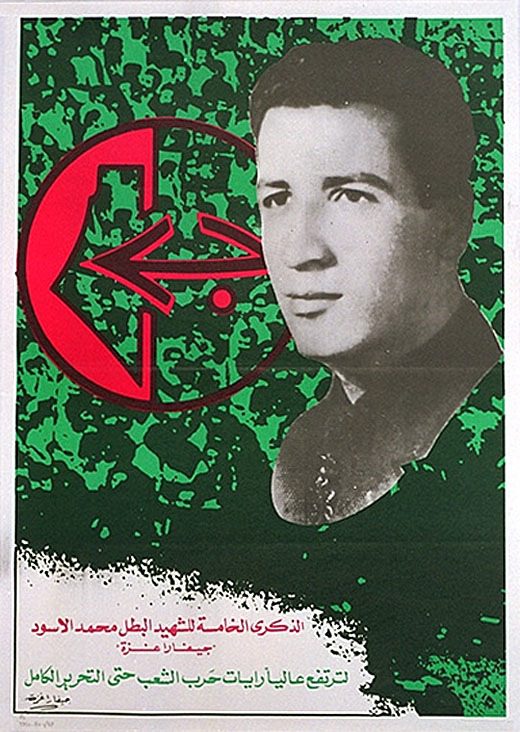

As for Palestinians, the Fedayeen fighters of the 1950s had little to do with the guerrilla culture with which they are now anachronistically associated. But this too was about to change, as during the 1960s Che forged a close relationship with the Palestinian Liberation Organization and a new generation of Palestinian fighters were heavily influenced by his example as well as by the global culture of resistance. Their moment to act came after 1967 when Israel occupied the Gaza Strip, settled in, and began making itself comfortable. In response, left-wing Palestinian guerrillas launched a sustained campaign that reached a zenith under the leadership of Muhammad al-Aswad, known at the time as the “Guevara of Gaza.”

Al-Aswad proudly carried Guevara’s legacy all the way to his tragic end, which came during a battle with Israeli soldiers in 1973. A few years later, due to a sustained Israeli campaign, Gaza’s left-wing Palestinian resistance movement was in ruins, and a decade later, the revolutionary left did not have much to offer. Indeed, by then, military opposition to Israel was organized along Islamic lines with organizations such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad taking a central role. Today, after two popular rebellions (intifadas) and after a score of other bloody skirmishes, all that is left of Che’s Gazan legacy is a few middle-aged Palestinians who, back in the 1960s, were given the name Guevara by their idealistic parents. So goes the history of Guevara in Gaza, an engagement that began modestly with a visit by an anonymous, cigar-smoking Cuban but ended, famously, with the making of an icon of resistance for Palestinians, one who sought to liberate his country as well as the world.

You may also like:

Yoav di-Capua’s FEATURE piece on his recent book, Gatekeepers of the Arab Past

Franz D. Hensel Riveros recommends Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image by Michael Casey (2009)

Edward Shore reviews Che: A Revolutionary Life by Jon Lee Anderson (2010)

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.