by Danielle Porter Sanchez

My father’s family came from Cape Verde, a tiny archipelago off the west coast of Africa near Senegal. Cape Verde was part of the Portuguese empire until a bloody fight for freedom initially led by my personal hero, Amilcar Cabral, brought independence to nation in July 1975. Nevertheless, my great grandfather immigrated to the United States from Cape Verde long before Cabral’s revolutionary days. My great grandfather, a carpenter, and great grandmother, a Cape Verdean palm reader and medium, whose family was from Portugal, settled in Nantucket in the early twentieth century. It would be naïve to say that Cape Verdeans found an accepting Massachusetts waiting for them upon their arrival, but the large diasporic community banded together and created an enclave that shielded them from the outside world in places like Nantucket and Fox Point. My family was part of that community until racial tensions began to build and fewer people associated themselves with their Cape Verdean heritage.  The family that my great grandfather and my great grandmother created faced an immense amount of discrimination as they attempted to build a life in America. Like many other Cape Verdean families, they denied their African background and started telling people that they were Portuguese. This allowed them to navigate the color line and sit in the front of buses, eat at segregated diners, and drink from whites only water fountains during a racially tense time in American history. However, attempting to pass as white during this time period did not completely erase their African ancestry in the eyes of their neighbors.

The family that my great grandfather and my great grandmother created faced an immense amount of discrimination as they attempted to build a life in America. Like many other Cape Verdean families, they denied their African background and started telling people that they were Portuguese. This allowed them to navigate the color line and sit in the front of buses, eat at segregated diners, and drink from whites only water fountains during a racially tense time in American history. However, attempting to pass as white during this time period did not completely erase their African ancestry in the eyes of their neighbors.

My father was raised in Boston during the 1960s and 1970s, a very tough place to be a young black boy, even if he did not identify as black. He had bricks thrown at him and was called a nigger more times than he can count. He was chased out of neighborhoods and threatened on a daily basis, which was perplexing for a young child who believed he was Portuguese. My brother faced some of the same challenges growing up in suburban Texas. He was called derogatory names and beaten up for being what others perceived as black. I’m not sure why, but instead of hiding from my ethnicity, I embraced the indisputable fact that I am, in fact, black and, through my mother, Mexican American.

In an attempt to trace my ancestry, I learned Portuguese to get closer to my grandmother, Irene. I remember when I called her and said “Bom dia” for the first time, she hung up on me. I did not understand why at the time, but as I look back, I can see the connection to the harsh sting of racism and the complications of racial identities in America. My grandmother never learned Portuguese. Rather, she was fluent in a creole language from Cape Verde that was spoken around her home. My ability to speak Portuguese was jarring because it illuminated this issue of a racial fabrication that began soon after her family moved to Nantucket and still exists today among my relatives. Whenever I mention Cape Verde to my aunts or uncles, it creates a tension in the room. Our heritage is something that has been silenced continuously from generation to generation. It is with great sadness that I write that I am one of the few self-identifying black people in my family. Yet, I have pride in who I am and where I came from. I have great love for the sacrifices that my family made, and my love for Cape Verde stems from a desire to know my family’s past more than words can explain.

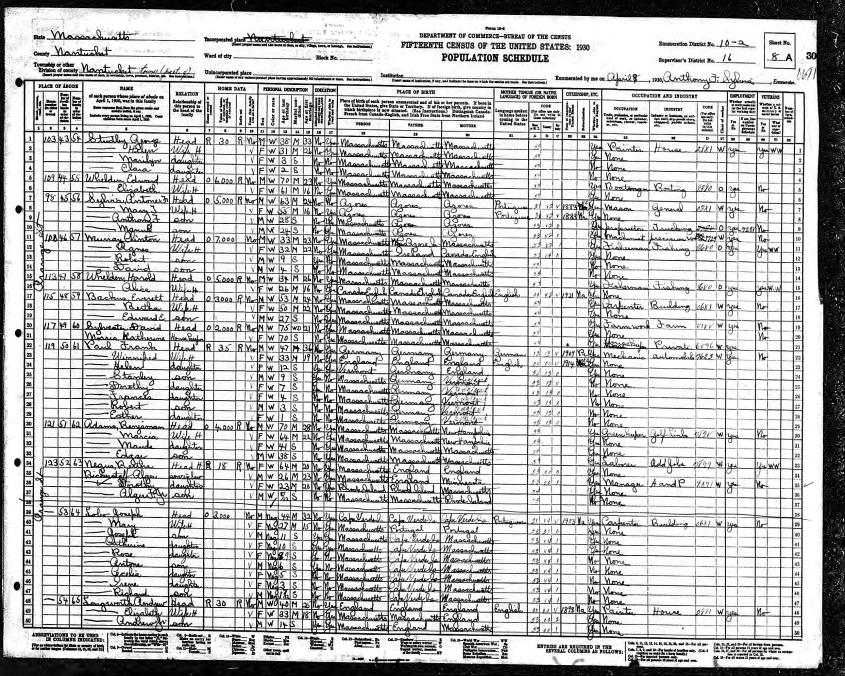

Five years ago, I gave my father a framed copy of the census document from 1930 that recorded our family’s immigration and is posted here. Lines 39-47 list my great grandparents and their children as immigrants from Cape Verde. Just looking at the document made me feel so much closer to a Cape Verdean community that I would never know. I swelled with pride as I wrapped it for my father and gave it to him on Christmas morning. I was surprised and saddened to discover that this gift caused great pain to my father and brother because they could no longer deny that our lineage led to Cape Verde. I do not know what my father did with my gift. A family member told me that he threw it out after I left, but I suppose it does not matter. Ultimately, I am part of a diasporic community that believed that it was necessary to redefine itself in the midst of some of most painful and degrading parts of American history.

I noticed something new when I examined the census record today; Joseph, Mary, Joseph Jr., Catherine, Rose, Antone, Cecelia, Irene, and Richard Lobo were the only “Negroes” identified by the census on their section of Orange Street in Nantucket. I am not sure what to think about this. Were they already attempting to pass at this point? Did they identify themselves as “Negroes” or did Anthony F. Sylvia, the census enumerator, give them that designation? Unfortunately, I will never know the answers to these questions, but what I can say is that I am almost positive that my great grandfather’s dream of finding prosperity and stability in the United States was drastically different from the harsh reality he faced as an immigrant in early twentieth-century America.

I cannot fathom the immensely painful experiences of my great-grandparents, grandparents, father, or even brother, but what I can do is push forward. For me, that means that instead of denying who I am, I can reflect upon the sacrifices of those that came before me, and I can take ownership for my heritage by learning from the hardships of my elders. Ultimately, I want to raise my son to know that he is (partially) Cape Verdean and to never be ashamed of that fact.

Photo Credits:

Danielle Porter Sanchez and Irene Rowe (nee Lobo), 2004

The 1930 census document showing the author’s Cape Verdean lineage