The Founding Fathers have been getting a lot of attention lately with the release of Hamilton on Disney Plus and the Pulitzer Prize being awarded to the director of the New York Times’ 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones. Among other issues, many posts online have called the Founding Fathers to task for their views on slavery. Historians have criticized Hamilton for scrubbing their records clean by portraying them as “young, scrappy, and hungry” immigrants in search of the American Dream;[1] alternatively, Hannah-Jones argues that independence was fought solely in the interest of maintaining slavery. [2] The question comes down to whether or not the Founders’ intentions were universally emancipatory or if their language of equality was a justification for taking control of profits from the colonial economy.

Returning to the Declaration of Independence may be instructive in examining this contradiction. The second paragraph, beginning with its most memorable lines, reads,

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, —That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect [sic] their Safety and Happiness.[3]

The paragraph can be read as a bold defense of people everywhere to rise up against tyranny when their rights have been violated, but some have pointed out that the three-fifths compromise, enshrined in the Constitution only a decade after its creation, contradicts the universalism of the statement “all men are created equal.”[4] Others have argued that the Constitution as it was originally written already protected slavery through its defense of private property. As historian David Waldstreicher writes, “The refusal to mention slavery as property or anything else in the Constitution means something. But what it meant was embarrassment—and damage control.”[5]

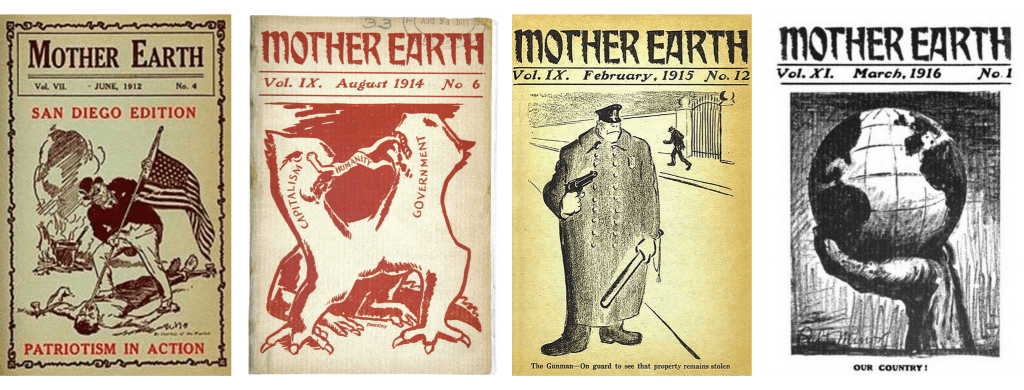

We don’t have to exonerate the Founding Fathers of their racism, sexism, or elitism, however, to reclaim the universality of their avowed commitment to “equality.” In fact, Emma Goldman already did precisely this in 1909. In her “New Declaration of Independence,” published in the journal she edited, Mother Earth, Goldman uses the language of the Founders’ text to subvert its original meaning and call for the abolition of the American government. She rewrote their famous lines to read:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all human beings, irrespective of race, color, or sex, are born with the equal right to share at the table of life; that to secure this right, there must be established among men economic, social, and political freedom; we hold further that government exists but to maintain special privilege and property rights; that it coerces man into submission and therefore robs him of dignity, self-respect, and life.[6]

Whereas the Founding Fathers attribute the guarantee of rights to the founding of governments, Goldman argues that governments exist only to enshrine special privileges in the law for the ruling class. In contrast to the Founders, who argued consent to be governed is given in exchange for the protection of certain unalienable rights, Goldman argues that the government robs the people of their rights.

Emma Goldman was a Russian-born political activist who immigrated to the United States in 1885 and landed in New York City, where she became involved in the progressive movement. She was famous for her advocacy of violence as a means of revolutionary upheaval, but she was not involved in the assassination of President William McKinley, in which she was implicated. Ultimately, in 1919, however, she was deported by the American government for her activism, along with other socialists, communists, and anarchists, and was sent back to the Soviet Union, where she soon became disillusioned with what she saw as the Bolsheviks’ authoritarianism. She spent the rest of her life travelling and lecturing throughout Europe and North America and also getting involved in the anarchist government in Spain during the Civil War. In addition to being known as an anarchist agitator, she was an early crusader for birth control and “free love,” believing people should be able to decide who and how they love without the involvement of the church or state.[7]

In the first two paragraphs of her New Declaration, she picks up on the “libertarian”[8] ethos of the original document by writing,

When, in the course of human development, existing institutions prove inadequate to the needs of man, when they serve merely to enslave, rob, and oppress mankind, the people have the eternal right to rebel against, and overthrow, these institutions.

The mere fact that these forces — inimical to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — are legalized by statute laws, sanctified by divine rights, and enforced by political power, in no way justifies their continued existence.

She goes on to describe the various ways in which the “American kings of capital” have committed crimes against the American people deserving of rebellion:

The history of the American kings of capital and authority is the history of repeated crimes, injustice, oppression, outrage, and abuse, all aiming at the suppression of individual liberties and the exploitation of the people. A vast country, rich enough to supply all her children with all possible comforts, and insure well-being to all, is in the hands of a few, while the nameless millions are at the mercy of ruthless wealth gatherers, unscrupulous lawmakers, and corrupt politicians.

In this paragraph, she points to the hypocrisy of such a rich nation denying the majority of its citizens the produce of their labor, instead hoarding it all in the pockets of an elite minority. This statement aligns her with the Occupy Wall Street movement’s critique of the 1% today. Both then and now, economic disparity has been great, as the economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman demonstrate in their article on the history of wealth inequality in the US.[9] Goldman’s text continues,

Sturdy sons of America are forced to tramp the country in a fruitless search for bread, and many of her daughters are driven into the street, while thousands of tender children are daily sacrificed on the altar of Mammon. The reign of these kings is holding mankind in slavery, perpetuating poverty and disease, maintaining crime and corruption; it is fettering the spirit of liberty, throttling the voice of justice, and degrading and oppressing humanity. It is engaged in continual war and slaughter, devastating the country and destroying the best and finest qualities of man; it nurtures superstition and ignorance, sows prejudice and strife, and turns the human family into a camp of Ishmaelites.

In the Bible, Ishmael was Abraham’s son with his wife Sarah’s Egyptian servant, Hagar. Sarah eventually told Abraham to cast Ishmael and his mother out into the desert where they nearly starved to death before God saved them. The “camp of Ishmaelites” Goldman is referring to are, therefore, people cast out by the powerful and made to starve. She is comparing their situation with the present when she writes, “Sturdy sons of America are forced to tramp the country in a fruitless search for bread.” Such deprivation of resources, she argues, leads to the degradation and oppression of humanity, breeding superstition and ignorance, prejudice and strife.

In another striking similarity to the present, rising inequality has taken place alongside an increase in superstition and ignorance with the proliferation of conspiracy theories, skepticism of science, and belief in occult practices like tarot and astrology. The President himself encourages this kind of behavior as a way to pander to a class that sees itself as “cast out” by neoliberal policies into a post-industrial “desert” of unemployment and scarcity. While right wingers swallow hydroxychloroquine, millennials compulsively check their horoscopes.

We, therefore, the liberty-loving men and women, realizing the great injustice and brutality of this state of affairs, earnestly and boldly do hereby declare, That each and every individual is and ought to be free to own himself and to enjoy the full fruit of his labor; that man is absolved from all allegiance to the kings of authority and capital; that he has, by the very fact of his being, free access to the land and all means of production, and entire liberty of disposing of the fruits of his efforts; that each and every individual has the unquestionable and unabridgable right of free and voluntary association with other equally sovereign individuals for economic, political, social, and all other purposes, and that to achieve this end man must emancipate himself from the sacredness of property, the respect for man-made law, the fear of the Church, the cowardice of public opinion, the stupid arrogance of national, racial, religious, and sex superiority, and from the narrow puritanical conception of human life.

Here, she outlines her strategy for changing the present state of affairs through emancipation from private property, the law, religion, public opinion, national, racial, religious and sexual chauvinism, and puritanism in personal affairs, meaning, a tediously moral attitude toward one’s own conduct and relationships—Goldman is remembered for believing being a revolutionary does not mean one needs to become a nun, single-mindedly devoted to “the cause,” but that everyone has the right to freedom, self-expression, and “beautiful, radiant things.”[10]

In the above she also calls for the common ownership of the land, shared equally among all as a right derived from “the very fact of [one’s] existence.” The emphasis on existence here implies people are born with unalienable rights, not endowed with them by a “Creator.” In practice, the difference in derivation of rights may seem inconsequential, but, in fact, it goes to the very heart of Goldman’s political philosophy—anarchism recognizes no higher authority in life, whether God or the state, only the authority of one’s own conscience.

Unlike the original Declaration of Independence, Goldman’s text takes into consideration the racial and sexual prejudices of American society and their roots in capitalist exploitation. She demands not only freedom in the abstract but concrete economic, social, and political freedom. Without reference to God, she recognizes only the common inheritance of the land by each successive generation, making her text a proto-environmental statement as well. Her Declaration is a truly revolutionary one that seeks the liberty and equality of all, as opposed to the Founders’ one which sought only to establish an independent sovereignty in the colonies not subject to British rule and taxation.

[1] https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2016/10/correcting-hamilton/

[2] https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/12/historians-clash-1619-project/604093/. See Hannah-Jones claim, “Conveniently left out of our founding mythology is the fact that one of the primary reasons some of the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery,” here: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/black-history-american-democracy.html

[3] https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

[4] The compromise was reached between North and South on the basis of representation in Congress, with slave-owning Southerners arguing for the personhood of slaves to boost representation, while the less agricultural North requested slaves not to be counted. See https://www.britannica.com/topic/three-fifths-compromise

[5] See Waldsteicher’s article in the The Atlantic (https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/09/how-the-constitution-was-indeed-pro-slavery/406288/), which was written as a rebuttal to Princeton historian Sean Wilentz’ defense of the Constitution in the New York Times. Wilentz also spearheaded the letter campaign to denounce Hannah-Jones’ framing of the American Revolution in the 1619 Project.

[6] https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/emma-goldman-a-new-declaration-of-independence

[7] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Emma-Goldman

[8] I use libertarian in the context of European political history, meaning a largely socialist and anti-authoritarian tradition, not the contemporary American usage, which implies a philosophy of total self-interest and contempt for government assistance to the poor.

[9] https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/131/2/519/2607097

[10] https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/goldman/Features/danceswithfeminists.html

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.