It’s the afternoon of a hot summer’s day, and I am standing at the bottom of a staircase—with no handrails—that’s not so much set in to the side of a mountain as built on top of it. The stairs look solid from way back, but now that I’m standing in front of them … they’re kind of crumbly. And did I mention the part with no handrail?

Way up there, at the top of four hundred fifty five stairs, there’s a shrine whose gleaming silver dome is barely visible in the afternoon sun. That’s our destination.

Am I really going to do this? I ask myself, gauging the heat and looking at my nearly empty water bottle, but knowing that the answer is yes. Otherwise, why would I be here?

I’m in the Sentyab valley, somewhere on the border between Samarkand and Navoiy viloyets, in the Central Asia republic of Uzbekistan. I’m here with a small tour group of educators exploring the midsection of the Silk Route.

Sentyab is the site of Uzbekistan’s first, and as far as I can tell only, community-based tourism venture. There are four guesthouses in Sentyab, each owned by a family (ours was owned by two brothers) that welcomes visitors into their homes and offers a glimpse of life in an idyllic village setting.

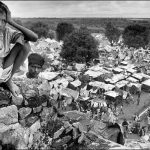

The village is spread out along a green valley on the north side of the Pemir mountains, a relatively low-lying mountain range that separates the more fertile part of the country where the main trunk of the ancient Silk Route runs from the drier steppes of Central Asia that expand north from where I’m standing to … well, they go a really long way.

On our arrival, we had been fed a typical “light” Uzbek lunch featuring the national dish, plov: a pilaf of meat, rice, carrots and currants. Also on the table was fresh bread—it’s always called non, cooked similarly to Indian naan in a tandoor-like clay oven—but the style differs from town to town with each region claiming its own as the country’s best. Apricots, apples, and mulberries were in season and served in abundance along with sweet melons, watermelon, salads of cucumber, tomato, and mint; fresh yogurt; and, just in case anyone was still hungry, toasted apricot seeds and dried fruits.

It’s little wonder that afterwards, most of us took a siesta on the veranda where we’d eaten, along the creek under giant mulberry trees, and then decided to take a walk through the village to wake ourselves back up. After all, dinner was coming in a few hours, and no one was even remotely hungry. What better to build up an appetite than walking up the side of a mountain?

As the others passed me, I slung my camera to one side and took the first few steps up the mountain. Once we got above the trees, there was a nice breeze! I quickly stopped counting the steps because the numbers weren’t approaching 455 as fast as I wanted. As we went up, the mountainside retreated, and the rail-less flight of stairs rose out of the side of the mountain a couple of meters. I focused on the dome above, trying to suppress my teenage vertigo. Just a few more steps …

Finally, we were there, atop the stairs—which was not actually on top of the mountain but on a ridge on the side. The structure was smaller than I’d expected—from the other side of the valley it looked massive!

And here I discovered one of the things that makes Uzbekistan unique. I’ve traveled in a lot of the Islamic world and it varies a lot from place to place. But here was something I’d never seen before.

“Is this a Buddhist shrine?” I asked our guide, slightly confused.

“No,” he said, pointing to the crescent on top of the dome.

“But … these are prayer flags.”

And, indeed, what I saw is almost identical to Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags in form and function.

The shrine is built over a spring whose waters are now diverted further down the mountainside. According to local legend, a local goat herder had been shown the location in a vision of Imam Ali, the Prophet Muhammad’s son in law. (This is a common story at many mountainside shrines; a much larger and more famous one is a pilgrimage site in the town of Nurota, where we stopped the next day on the way to Bukhara). Even though the spring has been in use since pre-Islamic days, locals still insist that Imam Ali was involved with its discovery.

Pilgrims come to this shrine and, as tradition has it, they tear off part of their garments, make a wish, and tie the strip of cloth to the metal railing. Eventually the cloth disintegrates and the wish is blown up to God with the intercession of the saints who guard the shrine.

It’s a tradition from the steppe, one of the many signs that you can find in Uzbekistan that the country sits aside the road between east and west: a Persian style dome sits atop an Islamic shrine, decorated with what I mistook to be Buddhist prayer flags, at a site that’s been revered since Zoroastrianism predominated here over a thousand years ago.

As the sun began to set over the valley and the smoke from several dozen cooking ovens began to rise above the trees, we started down the stairs to the path that would take us past the fields with the cows and goats, and the rooftops laden with fresh apricots and mulberries drying in the sun, to enjoy another home cooked meal in the veranda under the mulberry trees along the creek. We were the only visitors in the town that night, and every person on their way home from the fields greeted us warmly as we passed.

Uzbekistan, with its friendly people, natural beauty, and shimmering blue domed mosques and tiled minarets could very well be the next “hot” destination. I’m glad I got the chance to see it first.

Photo Credits: Christopher Rose

Stairs leading up to the Islamic Shrine at Sentyab

Sentyab Village

A “light” Uzbek lunch

View from the shrine

“Prayer flags” at the mountaintop shrine

The group with its Uzbek host family