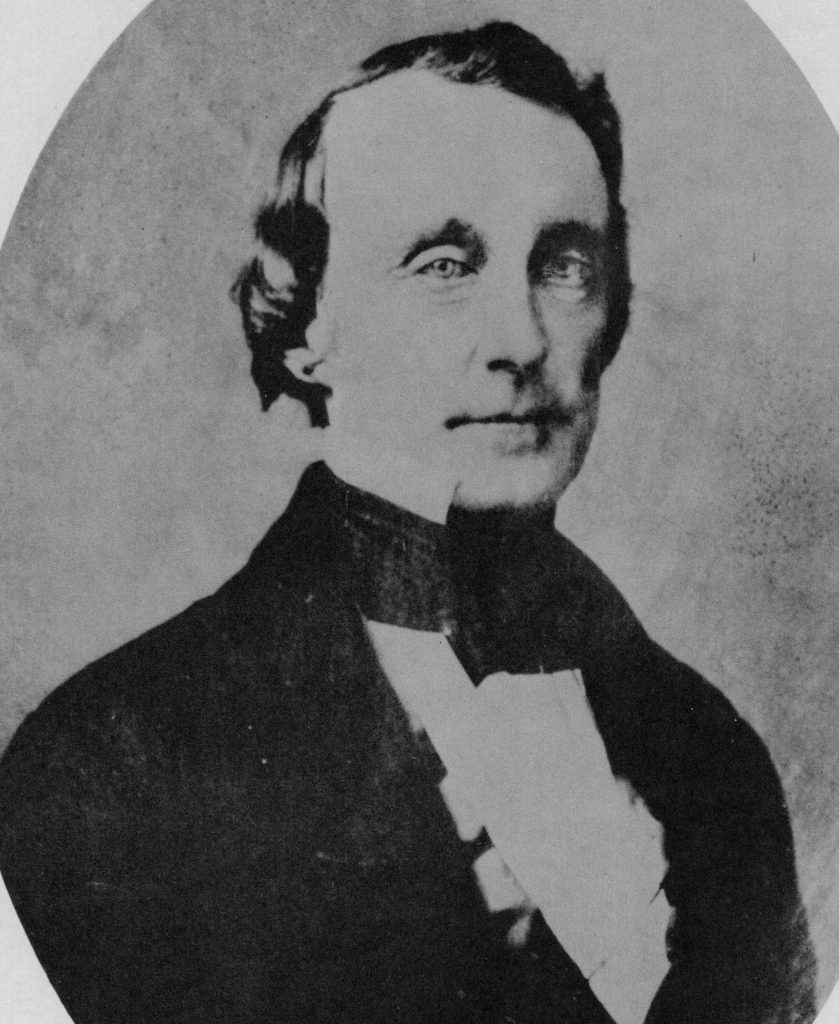

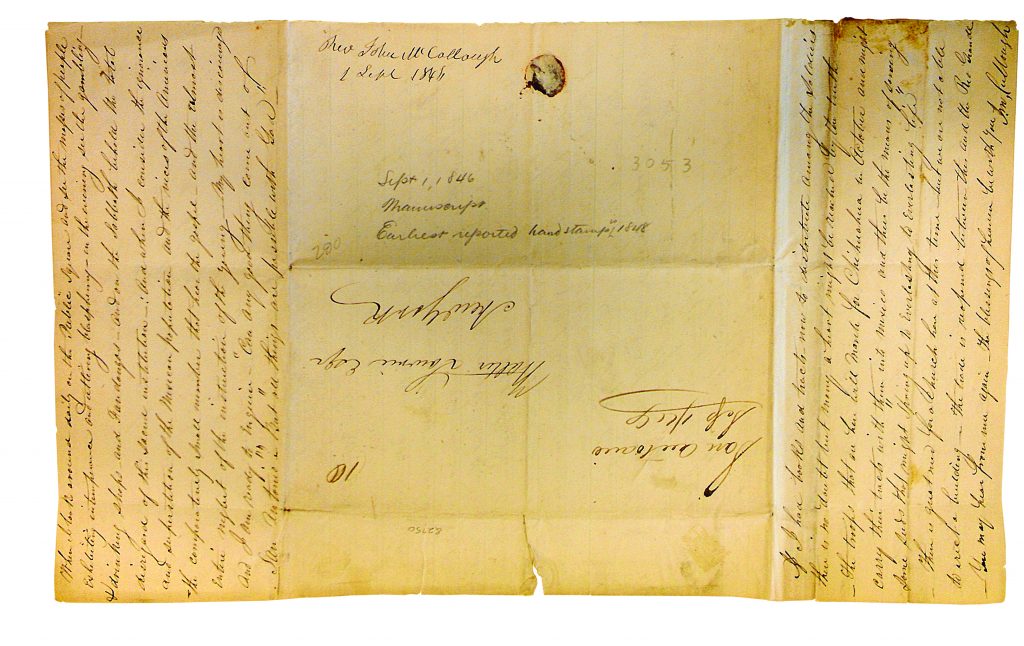

“Can any good come out of San Antonio?” This was the question at the heart of an 1846 letter penned by the Rev. John McCullough. He was writing to his Presbyterian superiors on the East Coast, who had assigned him the task of conducting missionary work on the new American frontier in Texas.

McCullough’s letter, housed on the UT Austin campus at the Briscoe Center for American History, is colorful, detailed, and dour, providing a rare first-hand account of a fledgling Texas community caught in the crossfire of the Mexican-American War.

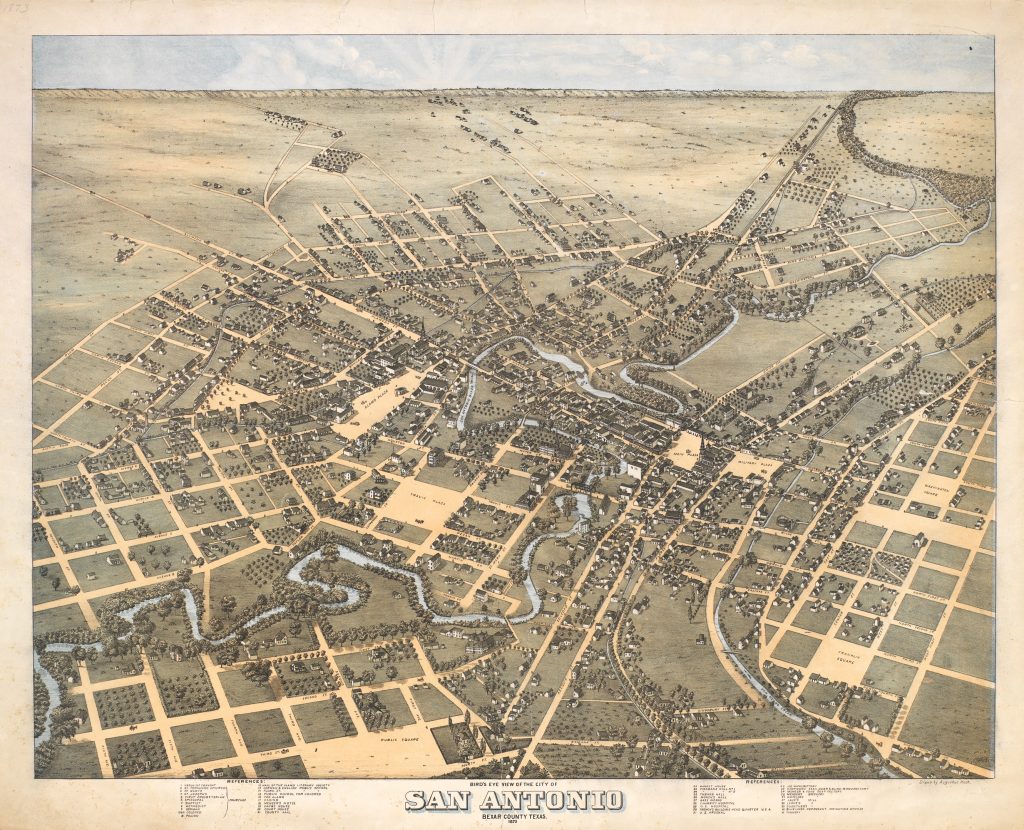

McCullough describes San Antonio as a cosmopolitan merchant town of 4,000 people, the majority being Mexican, with Anglos, Germans, and French making up the remainder. He notes that the city was filled with “traders from the Rio Grande,” as well as medical tourists — “travelers” there for health reasons. In addition, the town was “thronged with strangers” — a testament to the presence of 2,000–3,000 newly arrived U.S. troops. The mix of troops, tourists, merchants and locals created a moral landscape that made McCullough recoil.

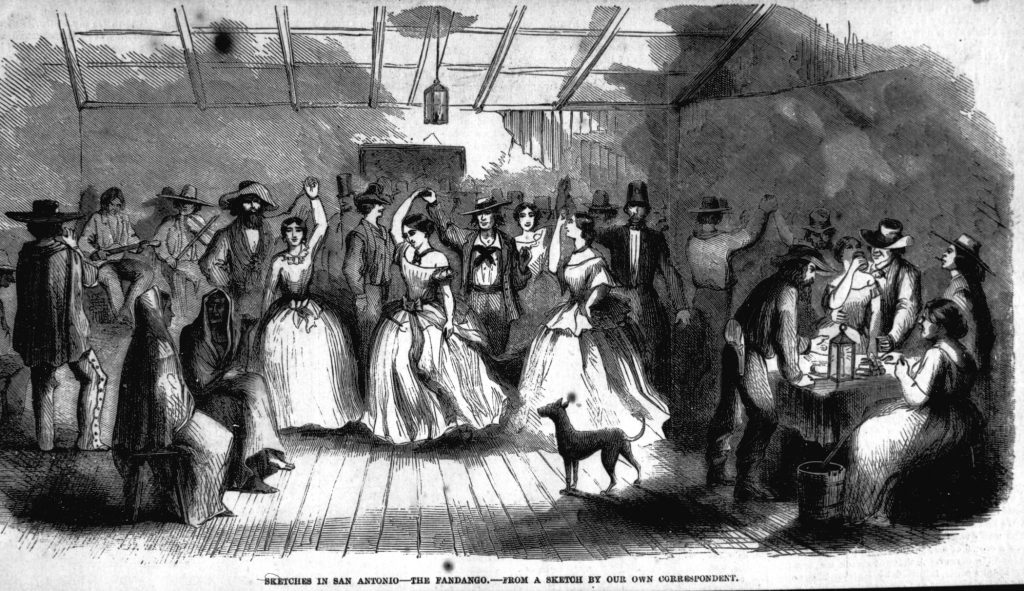

For the Reverend, San Antonio was a place full of “people exhibiting intemperance and uttering blasphemy.” Gambling was the “prevailing vice,” the sabbath was ignored and locals engaged in a “species of night frolics called fandangos.” It was also a place where priests kept cockerels “shod for fighting” in the church annex. Such men-of-the-cloth also had “a respectable posterity” of children “scattered throughout town.”

McCullough obviously experienced a significant degree of culture shock on the frontier. Of the other remaining accounts of San Antonio during the period, most are morally neutral, even celebratory. For example, in 1828, José María Sánchez and the botanist Jean Louis Berlandier passed through, Sánchez noting without prejudice that the “care-free” people were “enthusiastic dancers” while Berlandier spoke dancing as “the chief amusement among the lower classes.” In 1845, the traveler Frederic Benjamin Page described San Antonians as a people for whom “music and dancing, hunting and the chase, cards and love make up their whole existence.” In 1857, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. cheerily recalled a “jumble of races, costumes, languages and buildings,” a “free and easy, loloppy sort of life,” populated by women whose dresses “seemed lazily reluctant to cover their plump persons.”

Undoubtedly, McCullough’s spiky moralism was influenced by personal convictions and a desire to secure funding for his missionary endeavors. Nevertheless, life on the frontier was precarious and often tragic — factors which may have fueled the preachy intensity. According to R. F. Bunting, McCullough’s successor, the San Antonio of 1846 was a “miserable and dilapidated place,” wrecked by war and preyed upon by “desperados” and “undesirables.” Indeed, McCullough survived several attempts on his life by those who took umbrage at his use of the pulpit to rail against gambling and saloons. He had some success setting up a local school but in 1849 his mental health was failing. The same year, his wife died in a cholera outbreak and he moved to Galveston to recuperate with family members. After recovering his faculties he founded a seminary for women with his two sisters there. However in 1853 Galveston endured a severe outbreak of yellow fever. The school closed down — McCullough lost both his sisters as well as a nephew and niece to the outbreak. Dejected and defeated, he left for Ohio.

Despite his moral indignation, nervous disposition and chaotic life, McCullough ultimately waxed optimistic in his account of Texas: “Can any good come out of San Antonio?” His answer was identical to the biblical passage of John’s gospel that he was paraphrasing — “with God all things are possible.” But his faith in Texas was material as well as spiritual: “no doubt . . . this will, in a few years be a large town.” For McCullough, the area around San Antonio had enough rivers (with enough girth and fall) to build “manufactories” that could “surpass Lowell,” the Massachusetts town that had grown rapidly into a manufacturing powerhouse in the first half the 19th century. He also mused that central Texas might one day be the “best cotton growing region in the world,” a comment that underlined his ambivalence to slavery as much as his penchant for speculation. (McCullough was from a staunchly abolitionist family and preached to black congregations throughout his life. However one early 20th century account of him adds — rather euphemistically — that he “accepted southern culture.”) Perhaps it was his optimism about Texas that led to his return later in the decade. During the 1850s McCullough had married again (to a woman whose extended family owned several slaves) and apparently settled for a quiet life in Ohio as a salaried minister. But at some point in 1859, he decided to mess with Texas once more, moving to Burnet County in a wagon carrying his family and grand piano, and with plans, according to the Southwestern Presbyterian, to “preach in that destitute region” and found another school. It turned out to be a disastrous decision. The Civil War disrupted his fundraising and left him bankrupt. He died of apoplexy suddenly in 1870, leaving a widow and nine children. Obituaries remembered McCullough as a pioneer preacher and a kind man, despite the fact that his “attachment to principle [was] inflexible.” The adobe walled huts in which he used to teach English to street children had long since vanished from San Antonio’s streets. Today, he is commemorated by a five mile long stretch of tarmac north of Interstate 35: “McCullough Street.”

You May Also Like:

Family Outing in Austin, Texas by Madeline Hsu

Peace Came in the Form of a Woman, by Julliana Barr (2007)