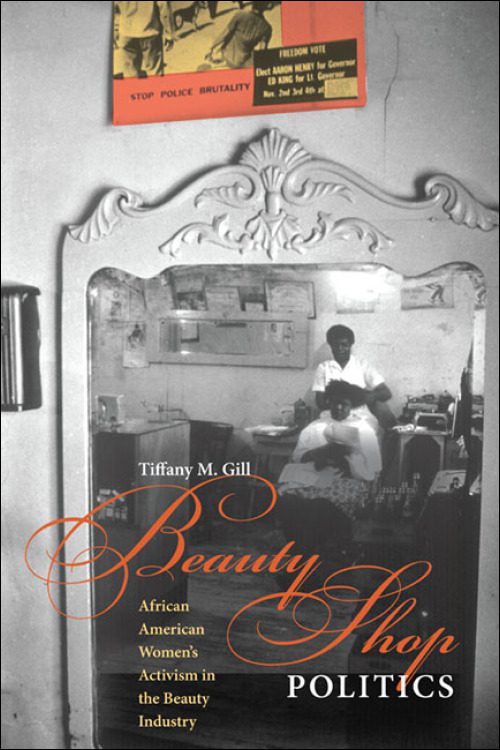

By Tiffany Gill

Bernice Robinson, a forty-one year old Charleston beautician, was surprised when she was asked to become the first teacher for the Highlander Folk School’s Citizen Education program in the South Carolina Sea Islands, for she had neither experience as a teacher nor a college education. This did not present a problem for Myles Horton, founder of the Highlander School. His main concern was that the sea islanders would have a teacher they could trust and who would respect them. In fact, for Horton, Robinson’s profession was an asset. In his autobiography, he explained the strategic importance of using beauticians as leaders in civil rights initiatives by declaring, “we needed to build around black people who could stand up against white opposition, so black beauticians were very important.”

This example illuminates some of the ways that beauty shops offered economic independence for the African American women who owned and operated them and provided a site for social and political activity. The black beauty industry has often been vilified for subjugating women and denounced for peddling products that denied an authentic “blackness,” but it should be seen instead as providing one of the most important opportunities for black women to agitate for social change both within their communities and in the larger political arena.

Myles Horton’s insight concerning the strategic importance of beauticians to African American political struggles was not simply a peculiarity of the Highlander Folk School’s Citizen Education Program. Other leaders of the modern Civil Rights movement also acknowledged the importance of beauticians. From Martin Luther King to Ella Baker, civil rights leaders openly acknowledged the centrality of beauticians in political struggles. However, it was not only in during the modern Civil Rights Movement that black beauticians were seen as key political activists. In the earlier part of the twentieth century, beauticians were the driving force behind war bond efforts during World War II and they were at the forefront of the push for black internationalism in the 1950s. Even earlier, some of the most active women in Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association and other black nationalist groups in the 1930s, were, ironically, beauticians. Finally, many of those most identified as reformers during the progressive era were black beauticians. In other words, beauticians are all over the historical record. Not only were they involved in these and other national and grassroots campaigns, but they were usually represented in large numbers, serving as leaders, mobilizers, and major financial contributors.

While the presence of beauticians in these major political movements may be surprising on the surface, their extensive activism makes sense when viewed in light of their status within the African American community. As entrepreneurs with a high level of economic autonomy, they had the freedom to engage in some of the most volatile political movements of the twentieth century. During the entire twentieth century, the black beauty industry was one of the only industries where all aspects were primarily in the control of black women. They served as the manufacturers, producers, and promoters of beauty products. These women built an economic base independent and beyond the reproach of those antagonistic to racial uplift and civil rights work.

Furthermore, black beauticians had access to a physical space—the beauty salon. As Robin Kelley has argued, Jim Crow ordinances forced places like “churches, bars, social clubs, barber shops, beauty salons, even alleys, [to] remain ‘black’ space.” These spaces, Kelley continues, “gave African Americans a place to hide, a place to plan.” Of all of the sites he mentions, the beauty shop is the only space that was not solely a “black space” but was simultaneously a “woman’s space” owned by black women and a place where they gathered almost exclusively. Whether a large salon in a four-story brownstone or a small establishment in a woman’s kitchen or patio, the beauty salon was one of the most important—albeit unique—institutions within the black community. Examining beauty shops and the women who owned and operated them gives unique insights into black women’s resistance strategies and political styles throughout the era of segregation.

Great Books on African American Beauty Culture

You may also like:

Tiffany Gill on Madam C.J. Walker here on Not Even Past