by Jacqueline Jones

Edmund S. Morgan’s book American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (1975) seeks to account for two related historical developments: The origins of American slavery, and the fact that many of the leading Founding Fathers–—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, James Madison, and James Monroe, to name but a few—owned enslaved workers. Seventeenth-century Virginia landowners cobbled together plantation labor forces from an unruly mix of Europeans, Native Americans, and people of African descent. Most field workers were young English indentured servants, bound to a master for a stipulated number of years. Homesick and forced to perform new and arduous forms of work—cutting down trees to clear forests, and then toiling stooped over in tobacco fields—these servants proved to be resentful members of plantation households. Within the first half-century of Virginia’s founding, a few white men with political connections owned most of the fertile lands in the eastern part of the colony. Once freed, former servants found themselves without money, land, or hope. Armed, they formed a dangerous element in the colony, and in 1676 launched a bloody challenge to the authority of elites, in the form of an uprising called Bacon’s Rebellion. Seeking to curb young white men’s violence, elites began to shift their workforces away from white indentured servants and toward enslaved peoples of African descent. Henceforth, even impoverished white men could become part of the large body politic, separate and distinct from the mass of black workers denied fundamental civil and human rights.

Morgan frames this narrative as a study in the history of poverty. The founders of Virginia, and the founders of the United States, were sensitive to contemporary conditions in England, where many workers remained chronically underemployed and resorted to theft and other forms of property crimes in order to survive. Under the system of American slavery, colonial elites believed that they had solved the problem of the poor as a dangerous, unproductive element in society. All white men could enjoy a measure of political equality, while all enslaved workers remained outside the bounds of civil society. Therefore, according to Morgan, it was no coincidence that many of the Founding Fathers owned slaves. A republican form of government worked best, they believed, if the dispossessed were excluded from it. In Morgan’s words, “Aristocrats could more safely preach equality in a slave society than in a free one.”

Morgan’s ground-breaking work reminds us that, when deployed by powerful people, racial ideologies constitute political strategies of immense force. Whenever my students encounter the word “race” in an historical text, I ask them to consider who benefits from these ideas. How are these ideas manifested in everyday life, and especially in patterns of work? American Slavery, American Freedom reveals that the institution of slavery was not a foregone conclusion, but the result of a series of conscious political decisions that would shape the nation for centuries to come.

In Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and ‘Race’ in New England, 1780-1860 (1998), Joanne Pope Melish explodes the myth that slavery in the North was a relatively benevolent system. In New England, early anti-slavery pronouncements stemmed less from enlightened humanitarianism than from fears that descendants of Africans had no place in tight-knit villages of English religious believers. In this view, the ideal citizen was a white man, a “freeman” who could perform several roles simultaneously—head of a household, father and husband; church congregant; landowner, and member of the local militia. The few enslaved blacks in the region were barred from owning land and serving in the militia; thus they represented perpetual outsiders in self-proclaimed “Godly” communities.

After the Revolution, the northern states began to emancipate their slaves, but several of those states passed laws that guaranteed freedom only for the children of current slaves. Even as free people, blacks in New England remained the target of discrimination. Many lacked the means or opportunity to buy land or pursue a trade. They were, in the words of Frederick Douglass, “slaves of the community” – barred from voting, serving on juries, sending their children to public schools, and even in some cases from moving around in search of jobs.

Many whites thus perceived blacks as a group of historically and perpetually poor people. Black leaders’ eloquent calls for full freedom alarmed whites, who responded with new racial ideologies. For example, many whites argued that black people were by nature dependent on charity; but some of these whites also held that black people aggressively sought out good jobs at good wages, in the process denying white workers of their privileges. Melish reminds us that racial ideologies need not be logical or consistent in order to shape a society, or a dominant group’s view of itself. The vicious anti-black riots that engulfed several northern cities in the 1820s and 1830s showed that devastating racial ideologies were not a regional phenomenon limited to the South, but rather a national phenomenon with southern and northern variations.

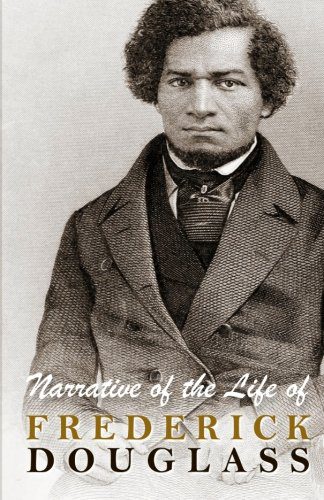

By any measure, Frederick Douglass’s Narrative (1845) is an extraordinary document—as autobiography, anti-slavery polemic, literature, and primary text illuminating mid-nineteenth-century American life. Douglass was born a slave on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1818, the son of a white father and an enslaved woman. One of the most moving parts of his story revolves around his learning to read and write. Literacy opened a whole new world to him, but also embittered him, as he contemplated the injustice of slavery. In 1838 he forged his name on a pass, disguised himself as a sailor, and escaped to Massachusetts. By the 1840s he was travelling throughout the North and Great Britain, electrifying audiences with his eloquence and his compelling story of escape from bondage.

I teach the Narrative in my Signature course (a seminar offered to first-year students) called “Classics in American Autobiography.” The students appreciate this text on many different levels, and eagerly engage in the discussion of a central question: How does one make a case for freedom in a time and place where many people assume slavery is a “natural” condition for a certain group of people?

Douglass crafted his Narrative to make the case against slavery in terms Northerners would understand. He focused not on a call for universal human rights—an argument that resonates with us today—but on the brutality of slavery and its effects on the family. Just a few pages into the Narrative he gives a graphic description of the whipping of his Aunt Hester by her lascivious owner; stripped naked and tied with her hands above her head, she endured a beating so vicious that her “warm, red blood (amid heart-rending shrieks from her, and horrid oaths from him) came dripping to the floor.” In order to counter the stereotype that enslaved workers were child-like and dependent, Douglass describes the “manly” confidence and pride instilled in him after winning a fistfight with an overseer. The passage where Douglass tells of his experience as a young slave, standing on a bluff overlooking the Chesapeake Bay and wistfully watching the white-sailed ships moving swiftly through the water, is one of the most beautiful in all of American literature.