In his seminal work, A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn presents a compelling alternative perspective on American history. In an important article, Professor Aaron O’Connell, who teaches at UT, made a powerful case for using Zinn in the classroom:

To take my students through the long history of violence in America, I use a book that has been in the news lately: Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. This book is well-known – even controversial, both inside academia and out – partly because Zinn tackles some of the sacred cows of America’s national mythos: Is Christopher Columbus better remembered as a genius sailor or a genocidaire? What does it say about the progression of liberty that single women in New Jersey had the vote until 1807 when it was stripped from them by an all-male state legislature? Most importantly, why have so many history books focused almost exclusively on the stories of white, wealthy men whose total numbers have never approached half – or even a quarter – of the country’s total population?

Zinn’s answer to all of these questions is that there have always been long-standing structural inequalities in American society that have shaped everything from the writing of laws to the ways they are interpreted to the stories we tell today about the nation’s past. It is nice to think of America as one big family, Zinn explains, but telling the story that way conceals fierce conflicts in that family’s history “between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.”[1]

In a class I took with Professor O’Connell, he challenged us to assess Zinn. In this article, I evaluate some of the flaws primarily related to his framing of economic issues that I saw within Zinn’s text. This does not diminish Professor O’Connell’s broader point that Zinn’s perspective is a valuable supplement to our historical education, but hopefully, it adds to the discussion and provides additional nuance in evaluating Zinn’s work.

Zinn sets out to challenge entrenched views of American history and to debunk what O’Connell describes as some of “the sacred cows of America’s national mythos.” While he succeeds in part, Zinn’s narrative reveals certain flaws. While I applaud Zinn’s goal, it is also important to maintain a fair and objective portrayal of events. I contend that Zinn’s selective use of evidence compromises the overall credibility of his narrative, exposing a lack of both an objective attitude and a comprehensive understanding of the economic system. Zinn asserts that, for government officials, the economy is “a short-hand term for corporate profit,” and their economic policies are primarily directed towards “the needs of corporations.”[2] This is a central strand of Zinn’s critiques, and it’s here that I will focus my attention.

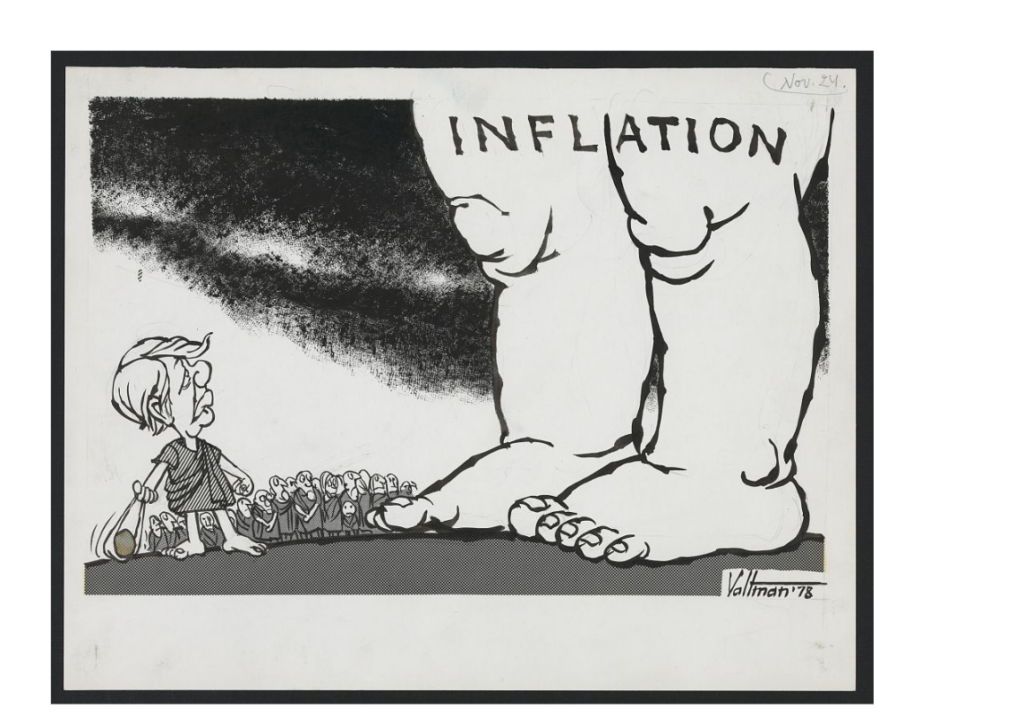

In supporting this sweeping argument about government priorities, Zinn neglects many crucial aspects of economics, such as the global events that were out of the control of the US government. For instance, his depiction of big oil and gas corporations’ profits and the public’s struggles with inflation and unemployment in the 1970s lacks a nuanced understanding of the economic factors contributing to the stagflation of 1973–1975 and 1979–1983. According to Alan Blinder, the 15th vice chairman of the Federal Reserve and an influential economist, the inflation of 1973 was pushed by a combination of special factors such as the food shock, the energy crisis, and wage-price control.[3]The first two factors were predominantly products of foreign conflicts and natural disasters beyond the control of the US government. Thus, a more critical approach would involve evaluating how well the US government managed the crisis by comparing its economic status to similar nations rather than hastily attributing domestic economic hardship solely to the government. Zinn’s work is powerful and illuminating, yet I think he sacrifices accuracy when it comes to economics as he tries to fit everything into one narrative.

Zinn tends to single out the United States, but detailed data from the Foreign Labor Statistics program shows that all major developed countries suffered from a surge in unemployment from 1974 to 1975.[4] Although the US had the highest unemployment rate in 1975–1976 and was affected the most by the stagflations of the 1970s, its economic state gradually improved during the 1980s. The unemployment rate remained one to two percent lower than in Canada and Europe, whose rates were generally lower than in the US back in the 1960s. Indeed, from 1960 to 2000, US unemployment rates improved from relatively high levels to the lowest among the G7 countries.[5] This suggests that the American establishment produced significant gains for people when it came to matters of employment. Zinn might argue that such decent economic standing was built on the expansion of American imperialism—a plausible assumption. However, this would contradict Zinn’s previous claim that government-promoted economic interests were solely the interests of corporations, as the majority of Americans seemed to have benefited.

In broad terms, Zinn views any abolition of price regulation or adjustment of corporate tax as a tool to advance corporate interests. The wage-price control system implemented by President Nixon was undeniably a deliberate policy adopted by the establishment. Zinn appears to endorse price control for its popularity, considering that he criticizes President Carter‘s end of price regulation as a departure from populism and embracing big oil and gas interests.[6] However, Zinn overlooks the start of this price regulation—Nixon’s wage-price control policy and the Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act. This legislation established a strict oil price regulation, setting a price ceiling of $5.25 a barrel for all the oil coming from wells drilled before 1973.[7] Instead of building his argument on this widely recognized government policy, Zinn presents a document meant only for the Arabian-American Oil Corporation’s internal deliberations to argue that “the system” always works in favor of the oil corporations.[8] This flawed presentation of evidence weakens his argument, as Zinn selects a corporate discussion, lacking meaningful implications about the government’s attitude, over an act passed by Congress as his evidence. Interestingly, the document Zinn cites was revealed by a Senate subcommittee investigating multinational corporations, indicating the government’s confrontational attitude towards oil corporations. It seems to contradict Zinn’s narrative of a government corrupted by the business world.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Furthermore, Zinn fails to acknowledge the disastrous effect of price regulation or comprehend the economics at play. Dr. Blinder identifies “the imposition and subsequent demise of wage-price controls” as the primary driving factor behind the 1973–1975 double-digit stagflation. The wage-price control system accumulated inflation as it struggled to maintain regulation, contributing to the dramatic price behavior in the market. As the price control system eventually collapsed, the surging catch-up inflation was released, leading to sharp accelerations and decelerations of nonfood and nonenergy prices in 1974.[9]

Zinn’s critique of corporate tax deduction, based on the correlation between low capital investment and lower corporate taxes in 1973–1975 and 1979–1982, ignores the context of double-digit stagflation during both time periods.[10] It’s far more likely that low capital investment reflects a weak economy, with the tax deduction being the government’s response to stimulate economic growth—an interaction evident, for example, in the relationship between governmental policies and national GDP during the COVID-19 recession.

In summary, Zinn selectively presents evidence while either disregarding or downplaying instances when the president disagreed with Congress, Democrats clashed with Republicans, or the primary goals of governmental policies were genuinely aligned with social well-being. Considering Zinn’s own sentiments expressed in his opening chapter, where he observes that nations are not communities and individuals cannot be viewed as a homogenous collective group, it becomes evident that what Zinn perceives as the establishment—the wealthy and government officials serving their interests—is hardly a unified group with shared objectives. Recent political events underscore that conflicts among political factions do not necessarily benefit the American people. Quite the opposite, a yearning for a return to an era characterized by political stability and harmony is discernible among many citizens.

Source: Library of Congress.

After reading A People’s History of the United States, I find that Zinn’s argument is persuasive in some ways but also suffers from selective use of evidence and inconsistency. He condemns Carter for demolishing price regulation yet does not credit Nixon for its creation; he talks about how the public should know that welfare only took a tiny part of the taxes, yet in the previous chapter, he boosts the success of popular movements marked by social spending taking thirty-one percent of the budget; he observes how the establishment used the press as a tool to inflame public opinion, yet he relies heavily on polls conducted by the press to directly reflect the supposed people’s will. While Zinn has undoubtedly covered essential and neglected facets of history, his selective and hypocritical use of evidence erodes the credibility of his major claims.

How can readers trust a historian to reveal the true history when he himself omits crucial contexts for the evidence he presents? How can people believe in the validity of a thesis arguing that specific economic concerns are the driving factor behind decision-making when the author himself cannot acknowledge the nuances of the modern economic system? How can people agree with Zinn’s cynical assessment of our political system when he himself fails to appreciate the complexity of it? The delicate balance between acknowledging historians’ inevitable personal bias, as Zinn himself admits, and maintaining an objective stance seems to elude Zinn. His work, while groundbreaking in many respects, may be perceived as crossing the line into the realm of subjective opinion on many occasions. Ultimately, this raises questions about the extent to which readers can trust Zinn’s narrative as an objective and comprehensive account of American history.

In the end, I’m more critical than Professor O’Connell, but I share his belief that Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States is a valuable text for the classroom. Despite its flaws, Zinn’s book is worth reading and writing about because it fulfilled the primary goal of academic research: it got me thinking.

Yunzhou Lu is an undergraduate computer science major who is also pursuing a Core Text and Ideas certificate as well as a history minor. He is a history enthusiast and is particularly interested in economic history, global diplomacy, and premodern military history. Yunzhou hopes to keep history learning a lifelong passion that brings fulfillment to his free time and gives him lenses through which to view contemporary issues.

[1] Aaron O’Connell, “Why Study the Ugliest Moments of American History? Reflections on Teaching Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States,” Not Even Past, October 3, 2020,

[2] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (HarperPerennial, 2015), 537-539 https://files.libcom.org/files/A%20People%27s%20History%20of%20the%20Unite%20-%20Howard%20Zinn.pdf

[3] Alan Blinder, “The Anatomy of Double-Digit Inflation in the 1970s”, Inflation: Causes and Effects, January 1982, 268-269, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11462

[4] Constance Sorrentino and Joyanna Moy, “U.S. labor market performance in international perspective”, Monthly

Labor Review, June 2002, 17

[5] Sorrentino and Moy, “U.S. labor market performance in international perspective”, 17-18

[6] Zinn, A People’s History, 532

[7] Christopher R. Knittel, “The Political Economy of Gasoline Taxes: Lessons from the Oil Embargo”, Tax Policy and the Economy 28, no.1 (2014):105-106, https://doi.org/10.1086/675589

[8] Zinn, A People’s History, 511

[9] Blinder, “The Anatomy of Double-Digit Inflation in the 1970s,” 266-268

[10] Zinn, A People’s History, 540

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.