The news headlines today tell an alarming if familiar story—of workers losing their jobs to machines, of the diminished power of labor unions, rising rates of economic inequality, and the inadequacy of the two-party system to address these issues in any meaningful way. The internet and other new electronic technologies might suggest that these are present-day challenges without historical precedent. In fact, the plight of workers today echoes the plight of workers in America’s Gilded Age. Then, 150 years ago, an array of activists working outside the two-party system sought to confront the titans of industry and the politicians who did their bidding.

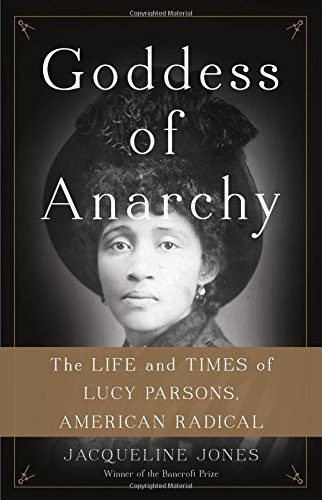

One of the most famous—and, to the self-identified “respectable classes,” infamous—of these activists was Lucy Parsons. Who was this prolific writer and editor and a fearless defender of the First Amendment and why did her speeches attract adoring crowds and baton-wielding police officers?

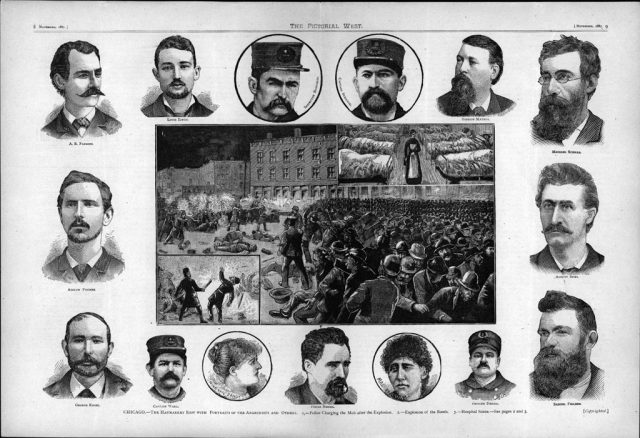

Born to an enslaved woman in Virginia in 1851, Parsons promoted the interests of the white urban laboring classes throughout her long life, right up until her death in 1942. For generations Parsons’s historical legacy has been subsumed under that of her husband, Albert Parsons, hanged in 1887 for his alleged role in the Chicago Haymarket bombing the year before. During a workers’ rally in May 1886, someone tossed a bomb into the crowd, killing seven police officers and four other people, and wounding many others. The identity of the bomb-thrower was unknown at the time, and remains a mystery to this day, but a biased judge and jury proclaimed Chicago’s anarchists guilty of murder and conspiracy solely on the basis of their radical writings and speeches.

“Police charging the mob after the explosion, Explosion of the bomb, and Hospital scene. Border images include clockwise from left: A.R. Parsons, Louis Lingg, Inspector Bonfield, Captain Schaack, Sheriff Matson, Michael Schwab, August Spies, Samuel Fielden, Officer Mathias Degan, Mrs. Parsons, Oscar Neebe, Nina van Zandt, Captain Ward, George Engel, and Adolph Fischer. Pictorial West. Vol. 11, no. 11 (Nov. 20, 1887)

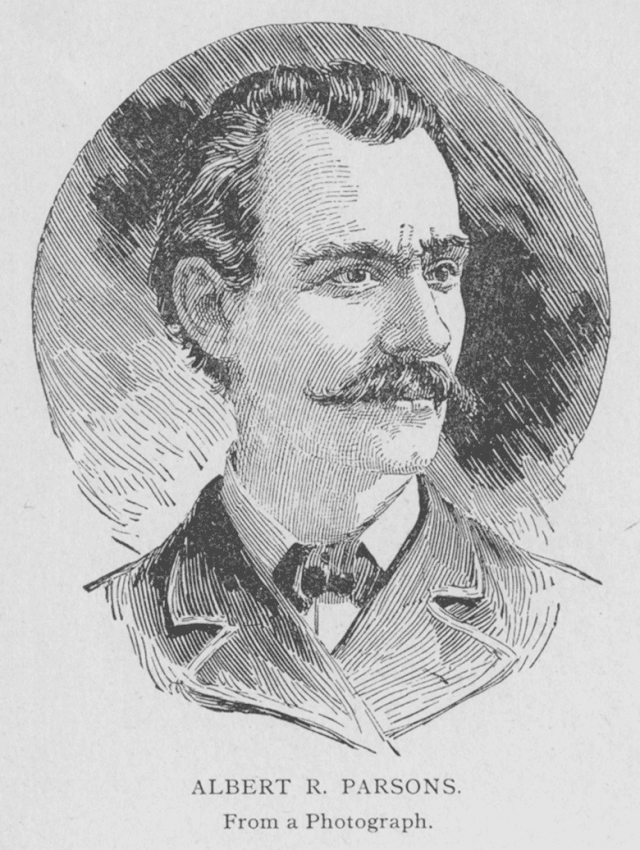

Lucy and Albert met in Waco, Texas, soon after the Civil War. The two made an unlikely, couple. She was tall and (according to the black and white men and women who knew her) strikingly beautiful; he was short, wiry and dapper, with carefully trimmed hair and mustache. He was a veteran of the Confederate army and the brother of a famous Confederate general. Lucy and Albert managed to marry in 1872, when Republicans sympathetic to black civil rights were in control of state politics; a year later the Democrats resumed power, and the couple fled to Chicago, where they settled in a German-immigrant community, embracing first socialism and then anarchism.

Lucy Parsons defiantly declared to newspaper reporters, “I amount to nothing to the world and people care nothing for me.” In this she was deeply mistaken, for a media frenzy swirled around her wherever she appeared. After Albert Parsons was jailed in the summer of 1886, Lucy embarked on a series of lecture tours in an effort to raise money for the defense of her husband and the other six defendants convicted with him. She was a powerful speaker—impassioned and eloquent, able to hold large audiences in her thrall for hours at a time.

The immigrant workers of Chicago revered her, politicians reviled her, and the general public maintained an intense fascination with her—all for good reason. Parsons lived a life that was rife with contradictions. She denied that she was of African descent, instead claiming that her parents were Hispanic and Indian. She remained largely indifferent to the injustices faced by black laborers, focusing her attention on the white workers of Chicago and other big cities. In private, she took lovers after the death of her husband, but in public presented herself as a prim Victorian wife and mother and a grief-stricken widow. She glorified the bonds of family, yet did not hesitate to rid herself of her son Albert Junior when he threatened to embarrass her by joining the U. S. army. In 1899 she had Junior committed against his will to an insane asylum, where he died twenty years later.

She was a well-read, insightful critic of Gilded Age America, advocating small cooperative trade unions as the building blocks of a more just society. At the same time, she became well known for her rhetorical provocations, urging the laboring classes to “Learn the use of explosives!” to protect themselves from predatory industrialists and police forces. In describing her, Parsons’s enemies often evoked the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. She was a “firebrand” who delivered “fiery,” “red-hot,” “incendiary,” “inflammatory” speeches that her critics feared would spark a bloody uprising among her followers.

The contradictions between Parsons’ mysterious private life and her defiant public persona was rooted in the struggles she faced as a radical, a woman, and a former slave, beginning with her forced migration from the East to Texas during the Civil War and her teenage years in Waco. In Chicago, she began a rigorous course of self-education, reading widely in newspapers and popular magazines as well as in dense tracts on history and political theory. Together with her husband, she participated in debates and discussions among leading radicals in the city.

In her writings, Lucy Parsons decried the effects of technological innovation on the workplace and the effects of money and influence on politics. Committed to the free expression of ideas no matter how radical, she edited several anarchist newspapers and contributed to many others. She impressed even those hostile to her and her ideas with her fluent denunciations of greedy capitalists and abusive bosses. She took delight in nimbly dodging the police officers who hounded her and tried to silence her. Her career reveals the challenges of promoting a radical message that would appeal widely to the toiling masses who were themselves divided by craft, religion, political loyalties, gender, and racial identity.

Lucy Parsons’s biography offers several overlapping narratives— a love story between a former slave and a former Confederate soldier, the rise and decline of radical labor agitation, the evolution of race as a political ideology and social signifier, and the trajectory of social reform from Reconstruction through the New Deal. She was a bold, enigmatic woman. Her power to inform and fascinate is enduring and her story, in all its complexity, remains a remarkable one for its useful legacies no less than its cautionary lessons.

Jacqueline Jones, Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical

For more about Lucy Parsons, anarchism, and labor, try these:

Paul Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy (1984). This is arguably the definitive account of the Haymarket bombing, written by the premier historian of American anarchism. Avrich covers all the major characters involved; workers’ movements in Gilded-Age Chicago; the rally on May 4, 1886; the subsequent trial; and the aftermath of the tragedy.

Gale Ahrens, ed., Lucy Parsons: Freedom, Equality, and Solidarity: Writings and Speeches, 1878-1937 (2004). This edited volume provides a good introduction to Lucy Parsons’s writings and speeches. She was a prolific writer of letters to the editor, essays and political commentary, and fiction. She also edited two anarchist periodicals, and delivered hundreds of speeches over the course of her long life.

Lucy E. Parsons, ed., Life of Albert R. Parsons, With Brief History of Labor Movement in America (1889). This book contains an autobiography of Albert Parsons, letters he sent to Lucy during his lecture tours, testimonials from comrades, and accounts of the Haymarket trial and its aftermath. Lucy published it to keep alive the memory of her martyred husband, and also to help support herself and her children. A reprint is available on Amazon.

William D. Carrigan, The Making of a Lynching Culture: Violence and Vigilantism in Central Texas, 1836-1916 ( 2006). Carrigan examines the anti-black violence that pervaded the area where Lucy Parsons and her mother and brother lived during and after the Civil War—McLennan County, Texas.

Michael J. Schaak, Anarchy and Anarchists: A History of the Red Terror, and the Social Revolution in America and Europe, Communism, Socialism, and Nihilism in Doctrine and Deed, the Chicago Haymarket Conspiracy and the Detection and Trial of the Conspirators (1889). Schaak was a Chicago detective who helped fuel fear and hysteria in the general public over labor radicals such as Albert and Lucy the Parsons and their comrades. He takes note of Lucy’s prominence in Chicago anarchist circles. This book is available online.

Margaret Garb, Freedom’s Ballot: African American Political Struggles in Chicago from Abolition to the Great Migration (2014). The Chicago radicals, socialists as well as anarchists, represented the white urban laboring classes exclusively, and steadfastly ignored the plight of black workers, whom they demonized as strikebreakers. Garb details the activism among black men and women in Chicago during this period.

Timothy Messer-Kruse, The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists: Terrorism and Justice in the Gilded Age (2011). Messer-Kruse carefully examines the transcript Haymarket trial transcript, and argues that the defendants were complicit in the bombing, to varying degrees. To some extent his argument relies on performances by Albert Parsons and other anarchists, who went out of their way to brag to undercover police about their possession of dynamite and willingness to use it.