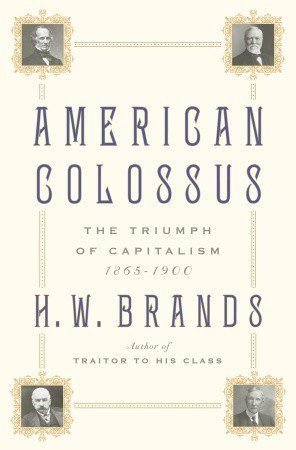

By H. W. Brands

During the quarter millennium since American independence, two institutions and sets of values have come to characterize American society: democracy and capitalism. Each had roots in the eighteenth century, but each blossomed only in the nineteenth century. Democracy emerged first, during age of Jackson, as ordinary people began exercising political power and electing candidates who seemed much like themselves. By 1850, while the practice of democracy left much to be desired (neither women nor African Americans could vote), the principle had become unassailable in American politics.

Capitalism emerged later, during what Mark Twain derisively called the Gilded Age. But it burst forth with an energy and thoroughness that made the final third of the nineteenth century the era of America’s capitalist revolution. The revolution transformed American finance, turning Wall Street into the hub of investment and speculation and New York the budding capital of world finance. The capitalist revolution reshaped the larger economy, converting America from a nation of farmers into a country of urban workers, managers and professionals. It recast American geography, pulling the recently feudal South into the web of capitalist commerce and exploiting the natural resources of the West. It altered American politics, injecting money into elections as never before and making the nurturing of American business the principal agenda of the dominant Republican party.

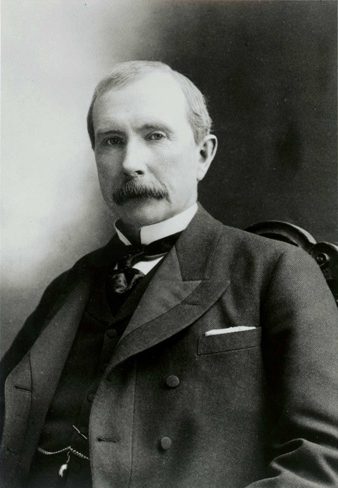

The capitalist revolution spun off personal fortunes for John D. Rockefeller, the titan of oil; Andrew Carnegie, the sultan of steel; J. P. Morgan, the master of money; and a hundred lesser winners in the capitalist struggle for profit and dominance. It drew millions of immigrants from Europe and Asia, men and women who dreamed of achieving not the enormous wealth of Rockefeller and Carnegie but merely a modest piece of America’s prosperity for themselves and their children. It built cities of brick and steel and concrete, of skyscrapers and mansions and tenements and slums. It lifted the average American to a standard of living never attained anywhere else in previous history, even as it intensified inequalities between the rich and the poor.

The capitalist revolution, like all revolutions, swept along the willing and unwilling alike. The winners outnumbered the losers, but they didn’t always outshout them. Farmers burdened with deflation-aggravated debt attempted to rein in the big capitalists. They created the Populist party and promoted candidates who promised to restore the traditional values on which the country had been built. Railroad workers, steel workers and other industrial laborers organized unions that waged strikes against their employers—and, in effect, against the government, when state and federal officials sided with the employers. Intellectuals challenged the ethos of capitalism, contending that the clamor for profit coarsened society and commodified life.

The capitalist revolution surged beyond American shores during the last decade of the nineteenth century. A withering depression caused merchants and manufacturers to seek markets abroad. A modern navy constructed in capitalist shipyards provided the means to extend American power to the far corners of the earth. The self-confidence the country’s bumptious growth had fostered encouraged Americans to emulate the imperial powers of Europe and Asia. In the 1890s the United States defeated Spain in battle, annexed islands and archipelagoes in the Caribbean and Pacific, and announced its entrance onto the stage of global power.

The capitalist revolution was the big story of era, but it was a big story composed of many small stories. Jay Gould was a young financier who grew a bushy beard to make him look older, and who remained calm during the tensest moments of difficult speculations, except for the telltale habit of tearing pieces of paper into tiny bits. Gould and his partner Jim Fisk, the P. T. Barnum of Wall Street, tried to corner the gold market in 1869 and nearly succeeded. They were foiled only at the last moment, when the federal government intervened. The ensuing turmoil wracked the financial world, jolted the broader economy, added “Black Friday” to America’s calendar of infamy, and nearly saw Gould and Fisk hanged from lampposts in lower Manhattan. James McParlan was a Pinkerton spy who infiltrated the “Molly Maguires,” the murderously radical wing of the coal miners of Pennsylvania. McParlan assumed a false identity, romanced the sister-in-law of one of the Mollies, and provided evidence that led to the execution of several of the radicals, some of whom quite likely were innocent of the crimes for which they were hanged.

Jourdon Anderson was a former slave from Tennessee. He emigrated to Ohio after the war, only to receive a letter from his former master inviting him to come back. Anderson declined the invitation, saying he preferred his life in the North. He asked his master to convey his regards to his old friends on the plantation. “Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.” Gertrude Thomas was the wife of a Georgia planter ruined by the Civil War; she tried to make the transition from the prewar slave economy to the postwar capitalist economy, and from the former culture of deference to the new one characterized—for a time, at least—by egalitarianism. But the old habits and thought patterns died hard in her, and her life gradually disintegrated.

Black Elk was an Oglala Sioux who, as teenager, fought in the battle of the Little Bighorn and scalped a federal cavalryman while he was still alive. He was an adult when the federal army had its revenge at Wounded Knee, in the slaughter of women and children on a frozen hillside in Dakota. Charles Goodnight was a ranch man who blazed one of the long trails from Texas to Kansas by which cattle drovers put beef on Northern plates and Texas on the map of the national economy. Howard Ruede was a Pennsylvania boy who went west to claim a homestead in Kansas. He built a dugout home from the virgin sod, but knew he’d never win a wife until he moved upscale to a proper frame house with windows, door and a roof that didn’t leak mud every time it rained.

Mary Fales was a Chicagoan who lost her home and the belongings she couldn’t carry when the Chicago fire of 1871 roared through the city and destroyed her neighborhood. She nearly lost her life but managed to reach the shore of Lake Michigan, where refugees from the flames waded into the water to avoid being roasted on the beach. Jacob Riis was a young Dane who fled his homeland for America when the woman he loved married another man. After several rough years he found his calling as an investigative journalist and photographer; his exposé How the Other Half Lives alerted the country to the poverty that existed within a stone’s throw of the great wealth of New York City. Chun Ho was a Chinese girl who was lured to California on the promise of economic opportunity on the “Gold Mountain,” as America was called in China, but who was forced into prostitution. As an illegal immigrant she feared going to the police, who anyway were in cahoots with the woman who pimped her out. Eventually she made her escape, but knew other girls who were murdered in the attempt.

By the end of the nineteenth century, many Americans had concluded that the capitalist revolution, for all the material benefits it conferred, had tipped the balance too far away from democracy. The complaints accumulated to the point where an unforeseen event, the assassination of William McKinley, pushed the pendulum back in the opposite direction. Theodore Roosevelt, McKinley’s successor, led a democratic counterrevolution that during the first half of the twentieth century reclaimed for democracy the ground that had been lost to capitalism, and more—preparing the way for another reversal, during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, in which capitalism was again unleashed, and which culminated in a bust that provoked new demands to rein in the capitalists.

H. W. Brands, American Colossus: The Triumph of Capitalism, 1865-1900

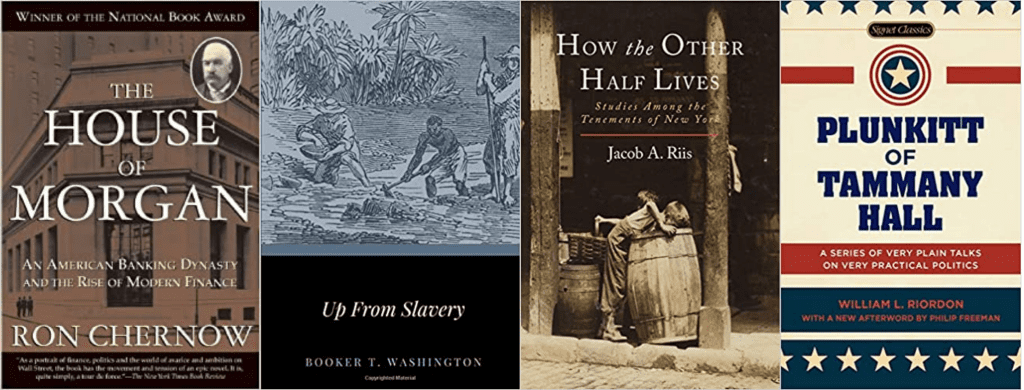

Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance (1991).

The best combination of narrative and analysis on the banking house that made J. P. Morgan the towering financial figure of his time.

Matthew Josephson, The Robber Barons: The Great American Capitalists (1934).

The classic muckraking account of the generation of industrialists and financiers who built modern American capitalism. More than any other book, this one is responsible for the shadow the captains of industry still labor under in history.

Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives (1957).

Danish-immigrant-turned-investigative-journalist prowls the Lower East Side with notepad and camera in hand, recording and depicting the lives of the desperately poor.

Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery: An Autobriography (1901).

The subtitle is “The Friendship that Won the Civil War,” a characterization that is not far wrong. Provides further insight into the warrior mentality.

William Riordon Plunkitt of Tammany Hall (1905).

A delightful primer on big-city machine politics, by a prominent politico. The machines have largely vanished, but Plunkitt’s philosophy still goes far to explain American politics.

Willa Cather, My Antonia (1918).

A beautifully crafted evocation of life on the Plains frontier, which was disappearing even as Cather wrote.

Black Elk, Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux (1932).

The last days of the free Sioux, as told by one of their medicine men.