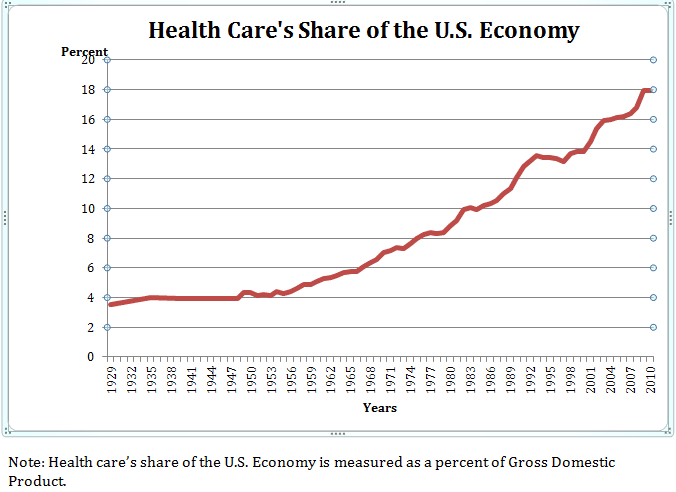

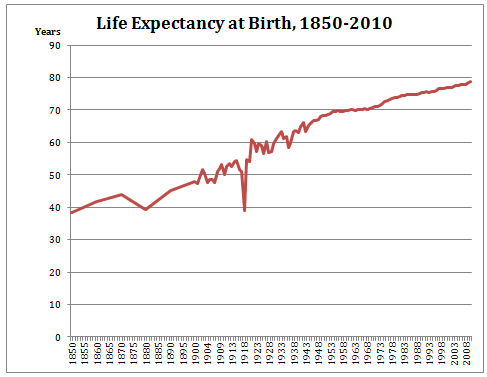

All the debates about health insurance have emphasized how expensive health care has become. According to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, as of 2010 (the most recent year available) health care constituted 17.9% of the U.S. economy. Health care expenses have risen steadily since 1929, as shown in the first chart. The second chart indicates that this expenditure has had a good payoff: life expectancy has risen from about 60 years in the 1920s to just short of 80 years today. (The big dip in 1918 reflects the influenza pandemic.) One task of historians is to identify disjunctures between the past and the present, and the two charts illustrate this point.

(Source: Historical Statistics of the United States: the Millennial Edition On-Line, series Bd33 and Ca74; Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures,” accessed May 11, 2012.)

(Source: Historical Statistics of the United States: the Millennial Edition On-Line, series Ab644; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012, Table 104; and Sherry L. Murphy, Jiaquan Xu, and Kenneth D. Kochanek, National Vital Statistics Reports, 60.4 [January 11, 2012], accessed May 11, 2012.)

Going back to 1929, health care claimed less than four percent of the economy, and less than ten percent of Americans had hospital or surgical benefits. Yet in the fifty years from 1880 to 1930, life expectancy rose from 40 to 60 years, or by the same amount as in the years since 1930. How was it possible for life expectancy to rise as much in the first historical era as the second without recording a surge in health care expenses?

A doctor examines a child before administering a vaccine in 1941.

Scholars point to two important improvements in life expectancy. First, there was a sharp fall in infant mortality. Massachusetts provides the best data on these early years. In 1872, 19 out of 100 infants did not live to see their first birthdays. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s the infant mortality rate remained above 150 deaths per 1,000. By 1929, however, the rate had fallen to 62 deaths per 1,000. Second, life expectancy improved because there was a drop in deaths tied to tuberculosis and other diseases like measles, typhoid, scarlet fever, and diphtheria. TB was the worst of diseases, but it dropped from 194 deaths per 100,000 in 1900 to 71 deaths in 1930. These declines came about before vaccinations were available, so what explains the drop in mortality rates?

A child waits to receive a measles vaccine in 1941.

One source for the rise in life expectancy was improved hygiene in the care of infants. A second source was improved public health, notably the eradication of bovine TB and the pasteurization of milk. Improvements also stemmed from better nutrition. Data is limited, and while from 1909 to 1930 per capita consumption of calories on a daily basis was flat, production of many fruits and vegetables, such as oranges and carrots, rose. Processed foods also became common. I would add another development: the fall in the workweek. During the late 19th century, Americans worked an average of 10 hours a day, six days a week. By the end of the Great Depression the workweek had shortened to roughly 40 hours a week. People did not physically wear out in the 1930s, as they had in the 1880s. They also did not suffer the number of industrial accidents that they had faced during the late 19th century.

In many ways, the two historical eras are not comparable. But there is one insight from this review of the years before 1930. To the extent that nutrition was important in the first era as a “cheap” way to boost life expectancy, nutrition remains one cost-effective strategy in reducing diseases like diabetes and raising life expectancy today.

All statistics are found in Susan B. Carter, et al., Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition Online (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Photo credits:

Arthur Rothstein, “Dr. Tabor examining Randolph Darkey, before inoculating him against measles, in the community health center, Dailey, West Virginia,” December 1941

U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black & White Photographs via The Library of Congress

Arthur Rothstein, “Elizabeth Darkey, daughter of one of the project families, waiting in the health center to be inoculated against measles. Dailey, West Virginia,” December 1941

U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black & White Photographs via The Library of Congress