What makes a history museum “work”? This is one of those things we don’t usually think about. As it happens, I love history museums. I especially like small, quirky museums in out of the way places with unique collections, in part because they are often conserved and curated by a devoted staff.

But I also love a grand museum with an epic story to tell. In the past year I drove from Austin to Los Angeles and back, and from Austin to Michigan and back, and I’m spending this semester in England, all of which has given me a chance to visit an astonishing variety of history museums, and to start wondering what made some of them so wonderful and some of them so – meh.

I hope to write about some more of these in the future. And I hope that you, our readers, will send us something about your favorite history museums. Send in a paragraph (or more!) or just send us a photo and a caption and we’ll post it in our series on history museums. (You can use the Contact button at the bottom of our homepage.) We might even start to visit each others’ favorites!

A couple weeks ago I had a chance to compare three popular history museums in close proximity to one another in Liverpool. I should start by saying that I am reporting as merely a tourist who happens to be a historian. I haven’t done any special research, I don’t know the goals of the curators of any of these museums, I haven’t read much about how history museums are changing to make use of new technologies or to attract bigger crowds. And it was only by visiting a lot of museums lately that I began to think about what makes some more fun and satisfying than others.

Liverpool, like many seaport cities that had fallen on hard times, has turned to its historical sites – its Mersey River waterfront and docks – to revitalize its economy by attracting tourists. The dock area of Liverpool now sports three major history museums: the Museum of Liverpool, The Beatles’ Story, and the Merseyside Maritime Museum. It also has a branch of London’s Tate art museum, the Tate Liverpool, as well as hotels, coffee shops, and souvenir stores. And for readers of a certain age, there is a ferry launch just outside the Museum of Liverpool where you can catch a ferry ‘cross the Mersey.

The ferry docks just in front of the Three Graces, the three buildings that comprised the business center of the city during its 18th and 19th centuries heyday: the Liver Building, the Port of Liverpool Building and the Cunard Building. Altogether the area has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City.

I began my visit at the Museum of Liverpool. It was a busy Saturday afternoon and the place was packed with families. I like to see people in museums so I didn’t mind the crowds, but I immediately noticed that only a few of those people were really looking at the exhibits. It was quickly apparent why. The exhibit cases were full of diverse things in kaleidoscopic display: historical photos, documents, and colorful, everyday objects used by sailors and merchants and families living in the city, rich and poor. In fact, the display cases were as packed as the space around them, with a dizzying amount of stuff, but there was only the slimmest explanation or historical text. So there was a lot to look at but little to help make sense of anything.

Some historians may be glad to hear that there was no “master narrative,” but I wanted some kind of historical thread linking one period to the next, or linking social life to political life or to the shipping history of the port or to the history of the families looking on. The historical texts didn’t whitewash the history of the city. Liverpool’s connection to imperialism and the slave trade as well as to enrichment and impoverishment at home were clearly indicated and objects representing these large movements were on display. But no one could construct a coherent narrative with any nuance from the abundance of objects and the scarcity of text. One could, perhaps, see this kind of organization as a general introduction to history for young children and their history-averse parents who might want more things to look at and less to read. For me, on the other hand, this is a kind of looking without thinking that leads only to frustration. But I can’t argue with the crowds. The other museums I visited were much better at presenting history in ways that were more visually and intellectually stimulating, but they weren’t packed.

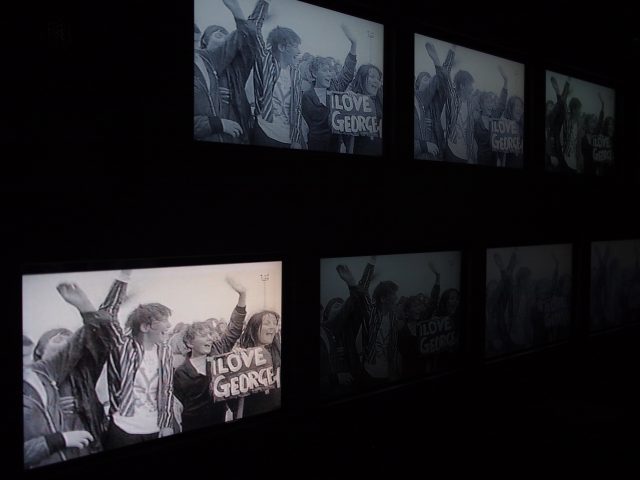

I left the Museum of Liverpool and headed for The Beatles’ Story, a little worried that it would be equally superficial and haphazard. I was also wondering if my familiarity with the Beatles and their story and pretty much everything Beatles would make it boring. I grew up with the Beatles; they introduced me to pop music at just the same time I got a transistor radio, which I listened to for hours every day. I wasn’t one of the screaming girls but I was the right age and one of my best friends was there in Los Angeles screaming her head off (for Paul) when the Beatles played the Hollywood Bowl in 1964. And I’ve watched all the films and documentaries since. So what could I learn? Why even go? Probably for the same reason we listen to the same song over and over again, we like familiar stories as much as we like to learn new ones.

So stay tuned. Over the next couple weeks I’ll report on The Beatles’ Story and then I’ll tell you about one of the best history museums I have visited, The International Slavery Museum at the Merseyside Maritime Museum.

In the meantime, send us pictures or tell us about your local museums, your favorite museums, or history museums you think we would all like.

Photos are all the author’s except where otherwise noted.