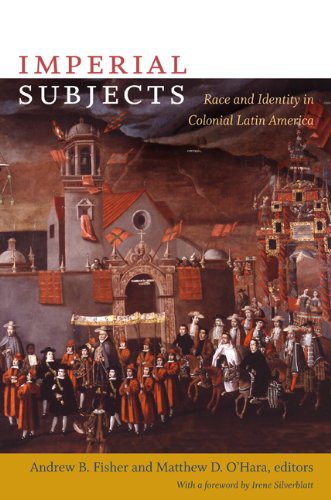

Since Douglas Cope’s seminal study The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City 1660-1720 was published in 1994, historians have understood the caste system, or sistema de castas, that categorised New Spain’s multiracial population as an elite construct to impose order on a disordered plebe, rather than a discourse that reflected existing, clearly defined racial boundaries. Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

Together the nine essays printed in this volume demonstrate that identities forged throughout Spain and Portugal’s empires in America were “fluid, malleable and constrained.” For example, Ann Twinam’s essay reveals that in the late eighteenth century mulattos and pardos from diverse parts of Spain’s Latin American empire petitioned the Council and Camará of the Indies to purchased whiteness. Mariana Dantas shows that in mid-eigtheenth-century Minas Gerais, the black brotherhood of Saint Joseph petitioned the King of Portugal for an exemption from a regulation that prohibited blacks and other people of “inferior condition” from carrying swords. Dantas emphasizes that this group of men justified their request on the grounds that they were loyal vassals, Christians, and skilled tradesmen; they evoked political, social and economic identities that they believed would override racial identity. Both Twinam and Dantas discuss the notion of ‘calidad’, which was a sense of the ‘quality,’ ‘state’ or ‘condition’ of a person that could be influenced by, but was not at all dependent upon, a person’s physical attributes including skin colour. ‘Calidad’ is a common thread that runs through many of the essays in Imperial Subjects that reinforces the impermanence of racial identity.

The expansive geographical and temporal scope of Imperial Subjects is a sure strength of this project; it persuades readers that the fluidity and malleability of racial identity was a defining feature of Latin American colonialism, rather than an anomaly. This collection has a strong footing in interdisciplinary analysis, borrowing theories from anthropology and cultural studies. The concept of ‘social identity’ attributed to the Norwegian anthropologist Fredrik Barth is deployed implicitly or explicitly within all of essays. Barth theorised that ethnicity was produced through processes of group interactions that defined boundaries, and therefore were inherently fluid.

Imperial Subjects may be faulted for giving the false impression that all historians have accepted the fluidity of identity in colonial Latin America. In a recent study Matthew Restall argued that the mobility of Africans and people of African decent in the colonial Yucatan was restricted to the ‘black middle.’ Although a porous line dividing enslaved and free blacks afforded blacks a degree of social mobility in this corner of New Spain, Restall insists that “men and women of African decent could never become full and indistinguishable members of the colony’s Spanish community.”

Can we accept both the fluidity of identity showcased in Imperial Subjects and Restall’s thesis of the ‘black middle’? The jury is out on this question. Yet Restall’s thesis is commensurable with Fisher and O’Hara’s view that the production of subaltern identities was fundamentally constrained in colonial Latin America. Fisher and O’Hara clearly state in their introduction to Imperial Subjects that this collection of essays rejects the “constructionist interpretation of personhood,” which they claim “places too much stock in the ability of individuals and groups to shape identities.” Imperial Subjects shows that power in colonial Latin America was fundamentally unequal, and draws our attention to the multiple ways in which the Spanish and Portuguese monarchies and transatlantic bureaucracies in Latin American imposed limits upon the range of identities that individuals and groups could assume or perform. Twinam and Dantes respectively demonstrate that the Council of the Indies and the Monarch had the power to determine the race and calidad of imperial subjects. Jeremy Mumford’s essay on indigenous nobles in sixteenth-century Peru highlights the power of local forces to render irrelevant identities approved by the Monarch. In pointing to the influence of the state upon the experiences of individuals and groups in colonial Latin America, this collection prompts us to ponder the present state of research into official colonial institutions. In contrast to race, gender and class, which have been the focus of countless studies in the past two decades, colonial institutions have received little attention from historians in recent years. If Fisher and O’Hara’s suggestion that we must understand colonial cultures and institutions in order to understand colonial identities, then historians should pay more attention to how these institutions operated and evolved.

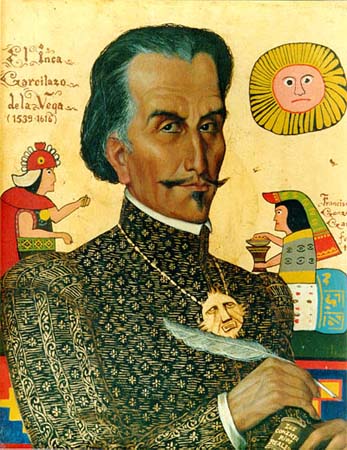

Garcilaso de la Vega, a sixteenth century Peruvian writer born to a noble indigenous family.

The contributors to this collection draw on a variety of sources to understand colonial institutions and identities, including demographic data mined from parish and census records, as well as petitions, and other items of correspondence between imperial subjects and the colonial bureaucracy. The editors acknowledge the limitations of these sources; specifically that they generally not written by the subjects themselves. Imperial Subjects is an important collection reflecting nine influential scholars’ current thinking about race and identity in Latin America before independence. Undergraduate and graduate students alike would do well to read this work.

Photo credits:

Bruno Girin, “Carmo Church Overlooking Ouro Preto, Brazil,” 2005

Author’s own via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Felipe Guaman Poma de Aya

via The National Library of Peru

You may also like:

Jorge Canizares-Esquerra’s review of Sabine MacCormack’s book On the Wings of Time: Rome, the Incas, Spain, and Peru.

Susan Dean Smith’s DISCOVER piece on images depicting racial mixing in colonial Spanish America.