In the spring of 1691, Louis Thebeaudeau, a shoemaker in the French city of Nantes, was asleep in a small room off his workshop when a ghost in the shape of his wife, Marie Monnier, woke him up. He was so astounded that he prayed on his knees for forgiveness of his sins. Only after he got back into bed “all trembling,” and the ghost pulled off the blankets and boxed his ears, did he think that it was actually his wife although she almost never came to his workshop as they lived in an apartment a few blocks away. They slept together. When he woke up alone in the morning, he presumed she must have left early to start her day’s work as a smalltime fabric seller. He presumed the events of the night meant that they were “reconciled” after a long period of conflict and so went to look for her. To his surprise, Marie said she hadn’t been there, so he must have seen a ghost and in fact had sex with the devil. Some months later, she went to court to ask for a separation. During the legal process, many neighbors testified about that evening’s episode and the couples’ many other marital difficulties, including their debts and his beating her.

The spectre of spousal discord that appears quite literally in this curious story illuminates a reality of many marriages, but the challenges the household faced haunted all families. Many of their seventeeth-century problems continue to haunt us: they had borrowed money they couldn’t afford to repay, their arguments included violence, their family, neighbors and co-workers watched, judged and sometimes interceded. Eventually their difficulties led to the involvement in the legal system.

Our continued familiarity with these dynamics indicates some of the ways in which marriage has always been a resource and a risk. For early modern men and women, getting married was an important source of potential financial stability. Husbands and wives both worked, sometimes in the same enterprise but more often in separate occupations like Marie and Louis. Young couples did not talk about being in love but about wanting partners who would work hard in a shared effort to make enough money to pay their rent, buy food, and take care of their families. Mutual success in these efforts meant that spouses were able to achieve a measure of stability in a precarious world. In many marriages though, individual shortcomings and the sheer pressure of daily life led to plenty of conflict, uncertainty, or worse.

More and more, early modern families relied on borrowing to make up the shortfall between what they could earn and their expenses whether quotidian (like food), periodic (like stock inventory or rent) and occasional (like dowries for daughters). Prices of food and rent rose while incomes stagnated in this early modern version of a familiar modern story of inflationary pressure on working families. At the same time, and for a related reason, the terms of borrowing changed. Price changes, income stagnation, and new lending terms were all related to the emergence of capitalism. A key feature of a market-driven economy, for example, was legal security for creditors and, in the seventeenth century, this security was sought both by new laws and by the increasing use of contracts rather than agreements made over a handshake. What difference did this make? Rents were one part of daily life affected by this shift. Traditionally, rent had been paid every six months, it was very common to be at least one payment in arrears – that is a year behind – and landlords often accepted payment in kind rather than cash. Gradually, though, landlords began to insist on regular payment in cash. For working families, almost all of whom were tenants rather than owners, this shift required a large, often jarring adjustment in their practices, including a rapid increase in landlords going to court to get eviction notices, which sent families fleeing in the middle of the night if they could not pay the rent they owed.

The use of force was a mundane and common part of early modern family life. Marie was known to have boxed Louis’s ears, and plenty of other instances indicate that husbands did not have a monopoly on domestic violence. Husbands, however, had the legal right to “discipline” their wives, which was accepted as long as it remained within limits. Court records show wives, their neighbors, families and co-workers actively resisted what they regarded as “excessive” violence and the legal system was quick to discipline husbands who were judged to have gone too far. These standards are far more accepting of violence than ours today, but paradoxically because the use of force in families was a matter of public knowledge and supervision rather than a hidden secret and source of shame, seventeenth-century wives were quick to complain about their husbands’ “abuse” and to seek assistance.

In these areas and many others, a transforming feature of the early modern world (and not only in France but across Europe and its global colonies) was the rise in the use of the legal system to help resolve domestic challenges. Litigation rates rose rapidly from the mid-sixteenth century. Individuals increasingly sought legal backing for their actions, both commercial (such as borrowing money) and personal (such as domestic violence). The French government, like that of other states, at the same time passed rafts of new legislation about personal matters, such as family life and sexuality, and public ones like the rights of creditors. As the state sought to increase its role in daily life, working families, women as well as men, more often decided to use the courts to help them manage the challenges they faced. With their decisions, repeated thousands of times in towns and villages and across many decades, families were key participants in making the new economic patterns we came to call capitalism as well as in new political developments we now associate with the emergence of centralized governments. The institution and experience of marriage itself was an integral element of the developments that came to shape the modern world.

Recommended readings on early modern Europe (linked page)

Natalie Z. Davis, The Return of Martin Guerre (1984)

A now classic work by the prominent historian exploring a sensational early modern family drama and how it played out in court in a village in southern France

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile: or On Education

An eighteenth-century bestseller, Emile criticized “traditional” families and advocated for a new mode of modern companionate, child-centered marriage that could be the literal cradle of citizens for democracies.

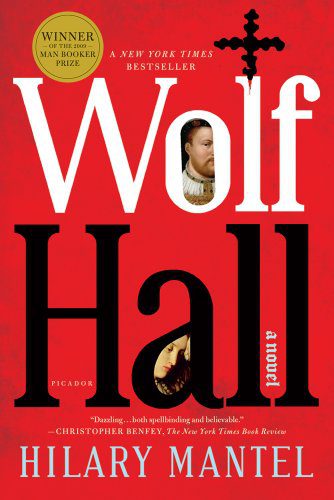

Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall: A Novel (2009)

A twenty-first-century bestseller and the 2009 Booker Prize winner, Wolf Hall includes a wonderful representation of family life in Tudor London intertwined with its better known narrative of the rise of Thomas Cromwell as a key adviser to Henry VIII.

Posted February 29, 2012

Photo Credits:

Adriaen Van Utrecht, Old Vegetable Seller (Wikimedia Commons)