By James Sidbury, Rice University

Note: This is adapted from a talk given at the Houston Museum of African American Culture.

The last several years have brought surprisingly quick if long-overdue changes to the politics surrounding memorials to the Confederacy and the soldiers who fought for it. Most recently Virginia, for so long the proud home of Robert E. Lee, repealed a law that denied local governments the authority to remove Confederate memorials from public display. More and more cities, counties and universities dotted throughout the south are, in fact, taking such steps—according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, 58 Confederate monuments have been removed from public display in the past few years, though, to be sure, that leaves the overwhelming majority of the South’s 1800 Confederate memorials standing. Even some seemingly successful efforts have had ambiguous outcomes. The decision by the University of North Carolina to give a Neo-Confederate group both the Confederate memorial statue that was removed from the flagship campus in Chapel Hill, and more than two million dollars to house and preserve it can hardly be seen as a simple triumph for progressive forces. What initially happened in Chapel Hill—the original agreement has subsequently been thrown out of court— underscores a complicated and largely unaddressed question: if one grants that memorials to the Confederacy should come down, what should cities, states and universities do with them?

The City of Houston has recently decided to move the “Spirit of the Confederacy” statue from Sam Houston Park to the Houston Museum of African American Culture (HMAAC), and in doing so it offers a promising solution to the problem. By moving the statue to the HMAAC the city asks Houstonians to confront the role that the actual spirit of the Confederacy has played in the city’s past and that it can play in its present and future. To understand what the city is asking requires a return to the moment when a group of community activists thrust the status of the statue into the public spotlight.

Confederate monuments have long been controversial, but a new urgency developed around them in 2015 when a white supremacist murdered nine worshippers at the Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston. South Carolina’s government responded by finally removing the Confederate flag from the statehouse grounds. A couple of years later Mayor Mitch Landrieu had several Confederate memorials removed from public display in New Orleans and gave a powerful speech explaining why. These actions spurred a defensive (and deeply offensive) demonstration by white supremacists to demand that Confederate memorials in Charlottesville, Virginia be left on public display. That demonstration took place on April 12, 2017 and culminated in the murder of Heather Heyer. The following weekend a coalition of anti-racist Houston activists organized a demonstration to demand that “The Spirit of the Confederacy” be removed from Sam Houston Park.

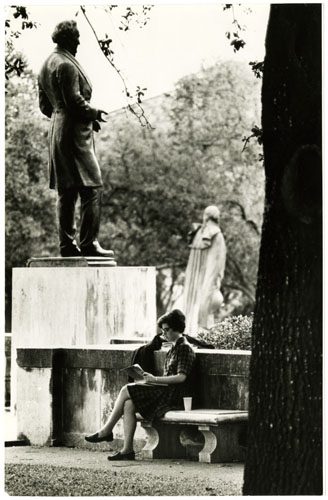

It was in many ways an odd demonstration. There was some kind of formal event at the park right before the demonstration began—perhaps a wedding—so there were people in tuxedos and formal dresses scurrying away as the crowd gathered for the demonstration. In addition to those calling for the statue’s removal, there was a small group of counter-protesters, as well as a large contingent of Houston police keeping the two camps separated. Those seeking to have the statue removed made arguments that are familiar to anyone who has followed this issue. They pointed out that those who joined the Confederacy had committed treason, and thus that their spirit hardly warranted public honor. Furthermore, they had committed treason in defense of slavery, and the memorial honoring them had been raised in support of white supremacy. For these reasons and more the activists argued that the statue should be removed.

But what the arguments arrayed against removing the statue? They too should be familiar, because we hear similar claims repeated each time the status of Confederate memorials is discussed. According The Houston Chronicle, those who wanted the statue to remain in the park “lamented what they called an effort to obliterate the past,” insisting that “you can’t keep going back and trying to erase history.” Concern about “erasing history” pops up frequently when memorials are discussed.

There is something intuitively persuasive about that argument, persuasive enough that many who hold no brief for white supremacy find it compelling. If the removal of memorials did indeed obliterate the past or erase history, it would certainly be a mistake. One of the very last things we should do as a city, as a state or as a nation is obliterate the history of the Confederacy or ignore the influence that history has had on how we have developed as a society. But the selective concerns of those who complain about the erasure of history suggest that the protection of history as a general proposition may not be their real concern. The recent past provides a clear test. In April 2003 a company of U.S. Marines helped a group of Iraqi men topple a statue of Saddam Hussein in a staged event that was replayed over and over again on newscasts throughout the United States. Anyone old enough to have been alive then surely remembers watching that statue fall. I don’t recall a single defender of history standing up to condemn the Marines for erasing it. I realize that may come across as a snarky effort to discredit an argument with which I disagree—and no doubt that’s one of the things it is—but I think the example is useful. Unless someone objected to taking down that statue—or, given the way that emotions of the moment can keep us from responding as we should, unless they think they should have and are making that case publicly—then it’s hard to believe that their objection to removing memorials to the Confederacy lies in their concern about the erasure of history.

But if the objection is not to the erasure of history, what is it? There is a simple answer and a somewhat more complicated and important one. The simple answer, the one that we all recognize immediately, is that the objection to removing memorials to the Confederacy is rooted in the desire to celebrate the Confederacy. That is why so many white supremacists fight to keep these statues in place. But what about the many others who are not white supremacists but who find something discomforting in the removal of time worn memorials?

Political tribalism surely plays a role. Too many of us are increasingly prone to choose our positions on myriad issues by noticing what our opponents are supporting and rushing to challenge it. I’ve certainly been guilty of that on more than one occasion.

But there’s something deeper and more important at play. Those who worry that removing memorials will erase history have it almost exactly backwards. Removing memorials represents an effort to make history. Mitch Landrieu made this point explicitly when he explained that by removing the monuments in New Orleans, he and the City Council had “not erased history”; they had become “part of the city’s history by righting the wrong image these monuments represent and crafting a better” one. This is a crucial point. Destroying monuments does not erase history. It makes it.

Don’t misunderstand me. Such acts are neither automatically good nor automatically progressive. Bad history is made at least as frequently as good history, and sometimes bad history is made by destroying monuments. The challenge we face when we decide whether to destroy or deface or remove memorials in our own society is the challenge of thinking through the value of the history we are trying to make. In New Orleans, Mayor Landrieu spoke passionately about the history that New Orleans sought to make when it removed Robert E. Lee from a prominent spot atop a traffic circle. At about the same time, a group of University of North Carolina students moved collectively to get Silent Sam, the statue commemorating UNC students who fought as Confederate soldiers, out of an honored spot at the center of campus. The University of Texas at Austin similarly removed Confederate statues from their perches along the perimeter of the central quad at the Forty Acres. In all three cases, history was made, but it was not erased. In all three cases, people decided that the Confederacy did not represent the values that should be memorialized at symbolic heart of their institutions.

What they didn’t decide, is what the Confederacy and its values should represent. UNC’s aborted attempt to wash its hands of the university’s relationship to the statue would be disappointing, even had it not included a decision to fund what was sure to be a pro-Confederate display somewhere else. But it has been hard to find a good solution. In New Orleans the offensive monuments have been placed in storage. UT has handled it slightly differently, putting the statues in the university’s historical collections, but the public effect is much the same. In both of these cases the removal of the statues constituted a rejection of the place of honor that those in power had once believed the Confederacy and its memory deserved, but there was no effort to establish and publicly represent the place it should have. And the Confederacy must have an important place in any true reckoning with who we are as cities, as states, as regions, and as a nation. It must have an important place in any true reckoning with how we have become who we are.

Houston took its time deciding how to handle “The Spirit of the Confederacy.” That deliberate pace surely caused frustration, but the time was not wasted. Mayor Sylvester Turner and the city have not simply removed the statue from its place of honor at Sam Houston Park to place it in storage. Nor have they given it to the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, where presumably it would have resided unseen in a storage warehouse. By moving the statue to the Houston Museum of African American Culture, the city exhorts us to collectively understand the spirit of the Confederacy first and foremost within the context of the history of racial oppression that has done so much damage to the city’s people, to its culture, and to American society. That may seem an obvious context. But it is shocking how rarely the Confederacy is explicitly memorialized in those terms in the United States. Collectively we have much preferred to embed our shared memories of the Civil War in other more comforting narratives. When the Confederacy is discussed outside of classrooms, one is more likely to hear of a tragic conflict pitting brother against brother, or of a battle for states’ rights, or of noble leaders forced to choose between loyalty to their state and loyalty to their nation. By entrusting the Museum of African American Culture to keep and display Houston’s representation of the Spirit of the Confederacy, the city asks us to remember the legacy of the Confederacy in a very different way. It asks that we confront the ways that Houston’s history is bound up first in the Confederacy’s effort to perpetuate slavery, and then in the ways that memorials to the Confederacy that were erected early in the twentieth century represented a commitment to the perpetuation of racial oppression. The city is not erasing the history of the Confederacy by moving the statue out of Sam Houston Park. It is making history by memorializing what we now see as the true meanings of the Civil War and of monuments to the “Lost Cause.”

You Might Also Like:

- Watch: “The Confederate Statues at UT”

- A (Queer) Rebel Wife In Texas

- The Racial Geography Tour at UT Austin

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.