From the editors: Not Even Past is delighted to publish this introduction to new research by four remarkable students in the History Honors Program at UT. Their groundbreaking research spans different periods and places and was conducted in the most difficult of circumstances dues to the COVID-19 pandemic. Undergraduate research is at the heart of the Department’s unique three-semester Honors Program. Other disciplines in the Liberal Arts offer Honors study for seniors only. Students in the History program begin a year earlier. As juniors they take a class reserved just for them: the Honors Historiography Seminar (HIS 347L) taught by the Honors Director annually. Students learn experientially. They visit treasured UT archives: the Harry Ransom Center and the Briscoe, exploring with curators documents on display selected to support their research interests. Successful Honors graduates return to share their theses and recount tales of research in archives and abroad. For more about the program see here.

Science, Socialism, and a Spark: The Life and Work of H.J. Muller – by Seth Hamby

The Pazzi Conspiracy: The Change of Power in Medici Hegemony – by Hubert Ning

‘Not a Work of Magic’: The Foundations of Women’s Mobilization in the 1968 Mexico City Student Movement – by Sara Greenman-Spear

‘You Have Not What You Ought to Have’: Sexual Transgression and Gender Nonconformity of Women in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century England

By Dawn McKamie

For the past year, I have conducted independent historical research on a History Honors thesis that discusses both the broad cultural perspective and lived experiences of gender nonconforming women in England in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-centuries. Pictured above, is an illustration of a pair of women who proved vital to my research—the Ladies of Llangollen, Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby. Descending from elite families, the two women grew up in Ireland in the mid-1700s and formed a close relationship after attending boarding school together. Despite immense pressure from their families, neither woman desired to marry a man and they began to form a plan to flee from Ireland and begin a life together, far from the affluent circles they felt trapped in during their youth. After a failed initial attempt, the two women left Ireland together in May 1778. The two women settled together in the remote Northern Welsh town of Llangollen in 1779, where they became permanent fixtures.

The pair began to engage in gender nonconformity immediately after leaving Ireland and arriving in Llangollen. It was reported in a firsthand account from the visiting comedian Charles Mathews that “there is not one point to distinguish them from men; the dresses and powdering of their hair, their well-starched neckcloths, the upper part of their habits…made precisely like men’s coats, with regular black beaver hats, everything contributing to this semblance…”[1] Eleanor and Sarah were wholly devoted to each other; they were inseparable for fifty years and admitted to having ardent love for one another. Despite these characteristics being treated with disdain and aggression by the print culture of the time, the pair was beloved by their community and travelers alike.

Why were these displays in gender nonconformance permitted by the community of Llangollen, when other such displays were met with harsh backlash? The answer lies at the intersection of class, location, and social activity. Overall, their existence was palatable to a society that preferred to neither see nor hear evidence of sins like same-sex attraction and excessively “deviant” gender nonconformance. The Ladies led fairly quiet lives, largely free from drama or scandal. Furthermore, their status as affluent individuals from historically important families likely afforded them a great deal of protection in society. Finally, at this time, Llangollen was sparsely populated — living in a small community in a remote location allowed Butler and Ponsonby to live as a couple and dress masculinely without fear of retribution that might have come from a larger, more publicized community. Though society in early modern England broadly abhorred gender nonconformity and same-sex attraction between women, these characteristics shielded the Ladies of Llangollen from any potential harsh backlash that was experienced by others who were not as fortunate.

[1]John Hicklin, “The Ladies of LLangollen, as sketched by many hands,” (Chester: Thomas Catherall, Eastgate Row, 1847).

Science, Socialism, and a Spark: The Life and Work of H.J. Muller

By Seth Hamby

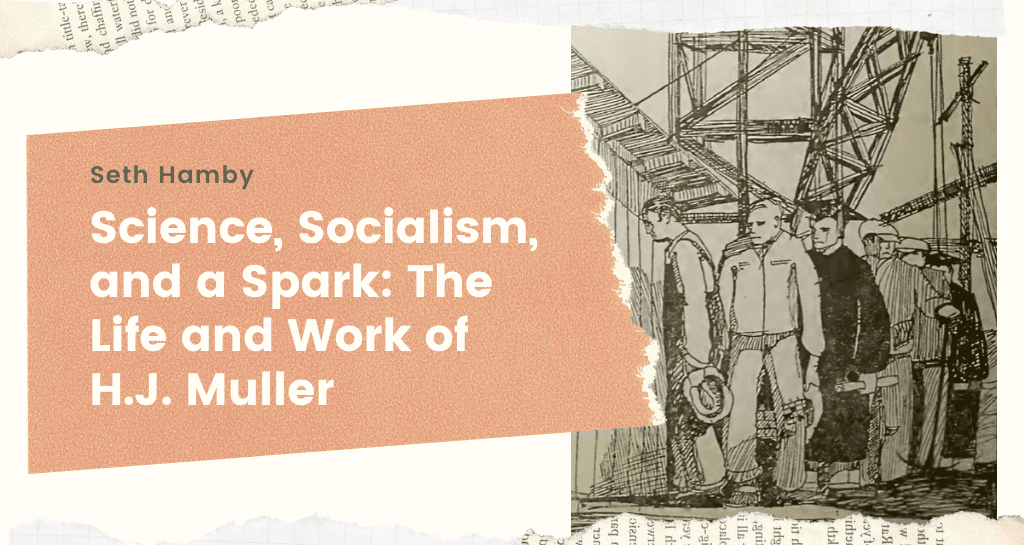

On June 1, 1932, a handful of young Marxists at UT Austin anonymously published The Spark, a monthly newspaper focused on student issues, race, class, and poverty. It was the only edition published. In less than a month, its writers were found and suspended. The Spark was in part a reaction to the desperation of the Great Depression; many students worked long hours for little pay or could find no jobs at all. Many more were outraged by Jim Crow era oppression, especially powerful in segregated Austin. The Spark expressed these grievances and demanded that students act.

The Spark articulated a common fear that the student body’s impoverishment was not a temporary symptom of the Great Depression but rather a permanent effect of capitalism. The Spark criticized the university for failing to pay “a legal or a livable wage.” They printed their solution in bold, saying, “Students and Workers! Form A United Front!” The writers also warned that “what is facetiously known as a minimum wage law” – recently passed by the Texas legislature – was simply an empty promise to pacify the masses. As the illustration below implies, neither a minimum wage nor the “benefits of higher education” will save the reader from capitalism.

The Spark was equally concerned with race, especially the disproportionate impact of the Great Depression. In a survey of 200 working-class families, The Spark noted the average white family spent a meager $1.15 on food per week. In contrast, families of color could afford even less, only seventy to eighty cents a week. When interviewing the respondents, they highlighted a few examples, including a recently laid-off couple that now had to rely on their disabled son to provide for the family. Similarly, a middle-aged African American couple had been surviving off a single bag of flour for the past month. They had been denied aid by the city of Austin.

Though The Spark was primarily written by students, genetics professor H.J. Muller had first inspired the idea. Throughout the process, Muller helped the students write and revise. After publishing the first issue, Muller sent a letter to a friend expressing his excitement at publishing a second issue. After an FBI raid on this friend’s home, the letter was found and turned over to the UT Board of Regents. My thesis focuses on the effects of the Regent’s investigation, alongside other Austin scandals, on the life and work of H.J. Muller, who would go on to win a Nobel Prize for his scientific research in 1946, many years after his unceremonious departure from UT Austin.

The Pazzi Conspiracy: The Change of Power in Medici Hegemony

By Hubert Ning

In the heart of Florence on April 26, 1478, hundreds of Florentines gathered in the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, awaiting the rites for the observance of Easter day. The cathedral was silent with the exception of the ringing of a bell. There was no movement except for the eyes in the room following the elevation of the host. Suddenly out of nowhere came a shout, a scream, and a thud. Medici blood has been spilled.

This event would become known as the Pazzi Conspiracy, a critical event to my thesis research regarding the power dynamics of the Medici during the Florentine Republic. The Pazzi Conspiracy was a failed assassination plot against the de facto ruler of Florence, Lorenzo de’ Medici, and his brother, Giuliano de’ Medici. While Lorenzo escaped, Giuliano would be left on the floor, murdered.

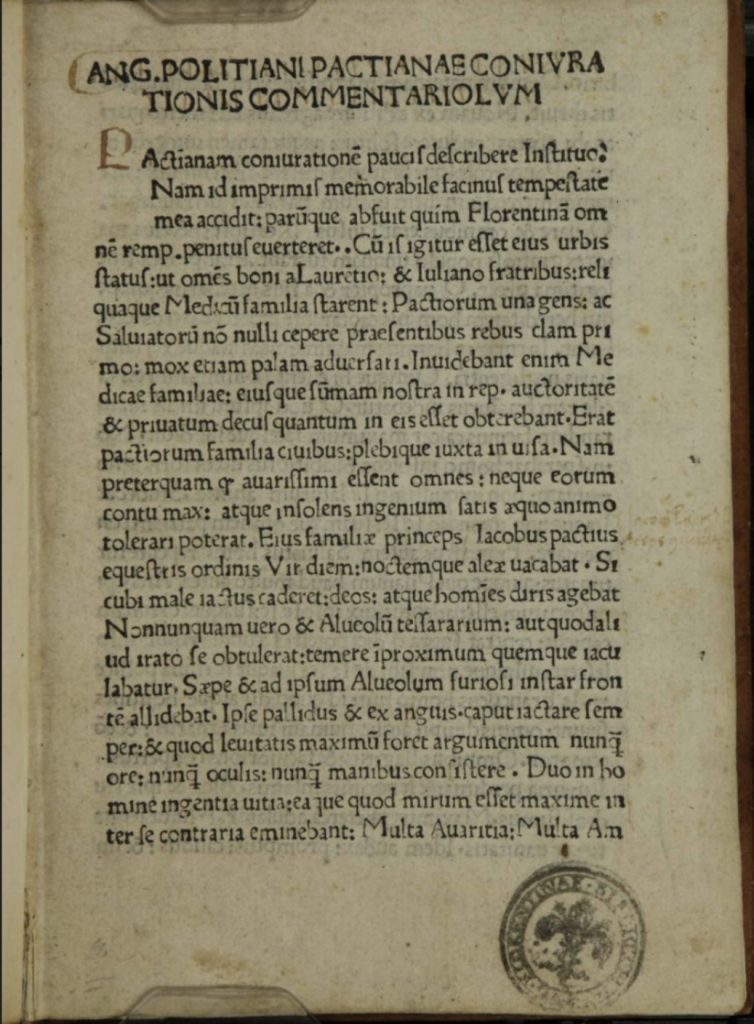

My thesis centers on one extremely important document: Poliziano’s Coniurationios Commentarium. Following the conspiracy, maintaining a robust public image was pivotal to Lorenzo. In order to maintain legitimacy as the de facto ruler of Florence, it was critical that the narrative of the conspiracy was told from his perspective, and not from that of the conspirators. To achieve this, Lorenzo resorted to the dissemination of Poliziano’s commentarium, which was written immediately following the conspiracy in 1478 and was an account of the attack and its aftermath.

Examining Poliziano’s commentarium we clearly see explicit bias and subjectivity. In every description of Giuliano de’ Medici, he is praised in the form of an eulogy. His words literally described Giuliano as if he was a Greek God. Similarly, Poliziano praises Lorenzo in almost every way possible. He states that the people would stand outside the Medici palazzo and “celebrate his well-being” and that Lorenzo alone, “[was whom] the Florentine Republic depended and in whom lay all the hopes and the power of the people…”

But Poliziano’s commentary was not just limited to praise. All the conspirators were made out to be evil heretics. Describing Francesco Salviati, the Archbishop of Pisa and conspirator, Poliziano states, “Out of rage, Salviati sank his teeth into Francesco Pazzi’s corpse…he held on with his teeth to the other’s chest, eyes frozen in an angry stare.” And in describing Jacopo Pazzi, Poliziano states, “Even as he neared the moment of his death, Jacopo never abandoned his raging and furious nature, shouting that he was giving his soul over to the devil.”

Arguably, Poliziano’s commentarium can be seen as propaganda. Poliziano was indeed painting a clear image of good versus evil, which we know is seldom the case in history. But more importantly, he attempted to give his commentary legitimacy by stating that everything he wrote was from an observational standpoint, whether or not it was true. The Pazzi Conspiracy was a key event in the Florentine Republic’s history. However tilted in Lorenzo’s favor, Poliziano’s commentarium provides a unique insight into the events of that day and a real glimpse into the past.

‘Not a Work of Magic’: The Foundations of Women’s Mobilization in the 1968 Mexico City Student Movement

By Sara Greenman-Spear

“The power to respond in ’68 with the velocity they responded cost a lot of work, no one takes into consideration that after the 26th and 29th of July a week passed until the schools started to go on strike. That was not a work of magic, but what represented a very wide organizational infrastructure, that had been consolidating for many years.”[1] – Martha Servín Martínez, interview, transcript in “1968, El fuego de la esperanza,” Raúl Jardón, 253.

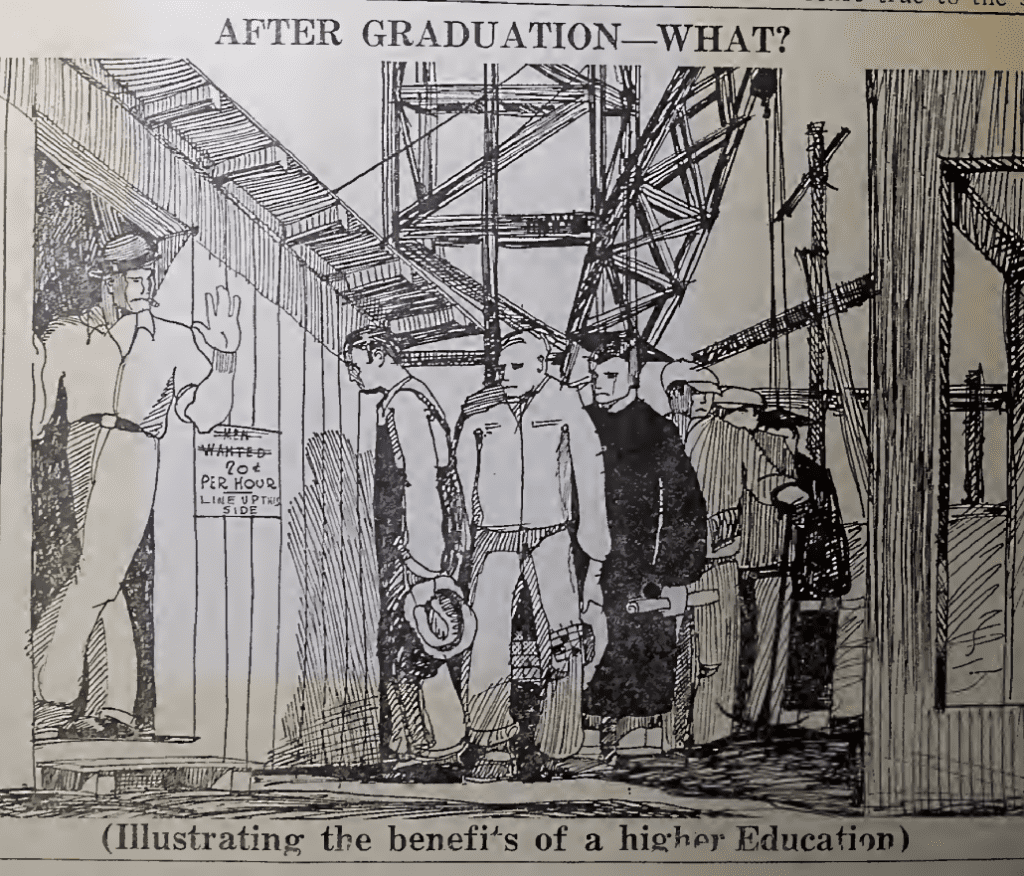

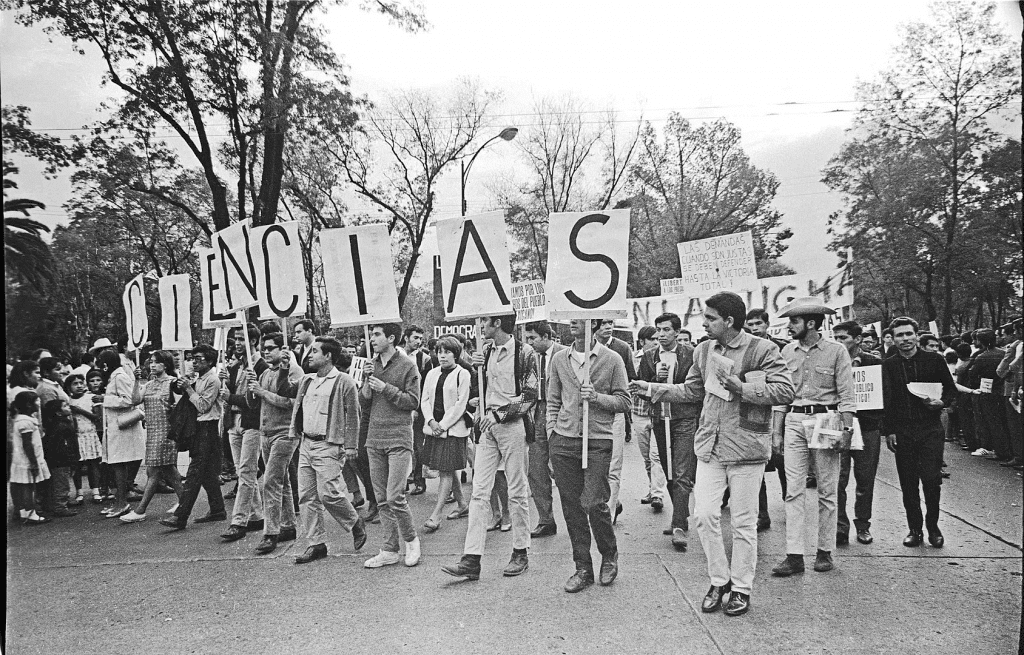

Martha Servín Martínez was a student studying biological sciences at Mexico City’s National Polytechnic Institute (Instituto Politécnico Nacional or IPN) when she joined a student movement in 1968. In late July of that year, a fight erupted between students from rival schools. While the fight may have remained a simple skirmish, the arrival of riot police known as granaderos heightened tensions as students viewed them as a symbol of the authoritarian Mexican government. As a result, this street fight became the catalyst for a series of protests by students against the government and their oppressive tendencies. These protests form part of what is now known as the 1968 Mexico City student movement.

I discovered Martha’s story and quote while researching for my Honors History thesis about the movement. The above quote, from an interview marking the movement’s 25th anniversary, shows that women were politically active before 1968 and relied on these earlier experiences during the movement. This challenges common narratives that suggest otherwise. The 1968 movement is often depicted as a watershed moment unlike anything that came before it. For women in particular, this often means a supposed lack of political involvement prior to the protests. However, as Martha explains, 1968 was not spontaneous but the result of years of careful planning and organizing undertaken by herself and other student leaders. Martha’s experience in student politics, in fact, dated to 1966, two years before the start of the movement, and included involvement in anti-war protests.[2] Those earlier experiences gave Martha the connections and knowledge to organize the new movement in 1968. For this reason, women’s involvement in the 1968 protests cannot be disconnected from their prior activism.

Other women who joined the 1968 movement besides Martha took many different paths, as a result of their unique backgrounds. No matter their background, I have found that before 1968, these women were not politically inexperienced as other researchers have suggested in the past. Some women joined via an association with student politics or radical political organizations. Others were former members of the party that had controlled the Mexican government for decades or had a family history of political engagement (a history that, in many cases, included these young women’s mothers). Even working women whose political roots came from labor organizing or women from mainstream religious backgrounds, two groups often not considered actors in their own right when it comes to the student movement, joined because they felt an affinity between the students and the beliefs they held. No matter the case, many of the women who joined the 1968 student movement had a previous experience in activism or politics, which shaped their actions during the movement and, in turn, shaped the movement as a whole.

[1] Martha Servín Martínez, interview, transcript in 1968, El fuego de la esperanza, Raúl Jardón (México, D.F.: Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 1998), 253.

[2] Antecedentes de Martha Servín Martínez, Archivo Sergio Aguayo, The Mexican Intelligence Digital Archives (MIDAS), Center for Research Libraries.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.