by Terry Orr

In 1963, the magazine Bulgaria Today, published by the communist government, surprisingly published an article showing a small selection of ancient Bulgarian Christian icons. At that time a large number of icons from as early as the tenth century through the seventeenth century were being displayed in the National Art Museum, the Ecclesiastical Museum, and the Archaeological Museum, all in Sofia; others were preserved in Bachkovo, Ohrid, and McInik. Although the magazine approached the religious works from the standpoint of art history, the icons themselves do not fail to show the spirituality they contained even in reproduction. The authors emphasized the early Church frescos as examples of the originality and independence of the artistic heritage of old Bulgarian art. The article, again separating artistic from the spiritual, states that early Bulgarian icon painting contained elements of human expression that distinguished it from the typical medieval Byzantine art of the eleventh and twelfth centuries characterized by abstract, empty, and gloomy images. Bulgarians, in contrast, were able to create images full of humanity, gentleness, and even spiritual life.

The very earliest of the stand-alone icons included in Bulgaria Today dates from the tenth or eleventh century and is a relief described as old Thracian Horsemen transformed into Christian Saints Georgi and Dimiter, two of the most recognizable military Saints of Christianity. Saint Georgi (St. George) is generally the most recognizable of the two, almost always depicted slaying a dragon. Saint Dimiter, better known in the West as Saint Demetrios of Thessalonica, was an Orthodox saint, martyred in the early fourth century and reported to reappear on the walls of the city in subsequent centuries to defend it from attacks of barbarians and protect the inhabitants from plague and famine. These figures are usually shown mounted on chargers with St. George riding a white horse and St. Demetrios a red one.

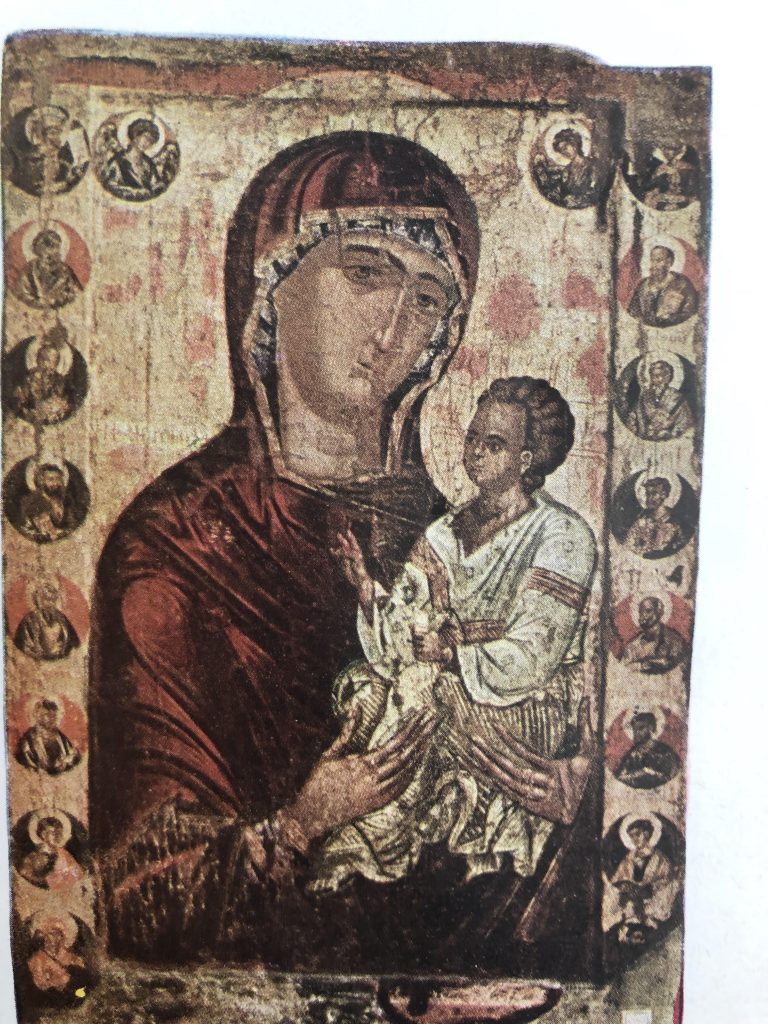

Two of the published icons depict the Virgin and Child in different poses. An icon of the fourteenth century shows the Theotokos (Mother of God) cradling the Christ Child, who is touching the face of his Mother in a style known as Tender Mercy or Eleusa. The second, from the seventeenth century, is posed in the Hodigrita style, with the Theotokos framed by the Prophets and holding the Child pointing toward God as a guide to salvation.

In addition to those icons shown in Bulgaria Today, other early Bulgarian icon paintings have been found in the ninth and tenth-century churches of Preslav. Icons were discovered in the church of St. Theodor, for example during excavations of 1909-1914 of the Monastery of Patleiena which was destroyed in 971. That icon has become a symbol of medieval Bulgarian heritage and is now held at the National Archaeological Museum.

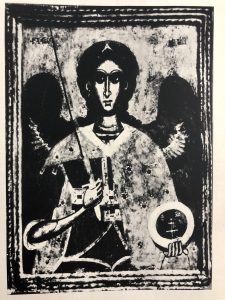

The magazine describes the style of these icons as linear and primitive but profoundly expressive and the basis of the folk icon-painting of later centuries This type of folk icon-painting is prevalent throughout the Balkans and can be seen at such places as the Orthodox Monastery in the small village of Voroneț in Romania. The monastery has icons exhibited on both the interior and exterior, somewhat reminiscent of the earlier twelfth-century Roman Catholic Cathedral at Chartres in France with its statuary of both Old and New Testament figures prominently placed on the exterior and the interior flooded with the light of its numerous stained glass windows.

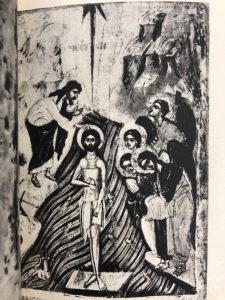

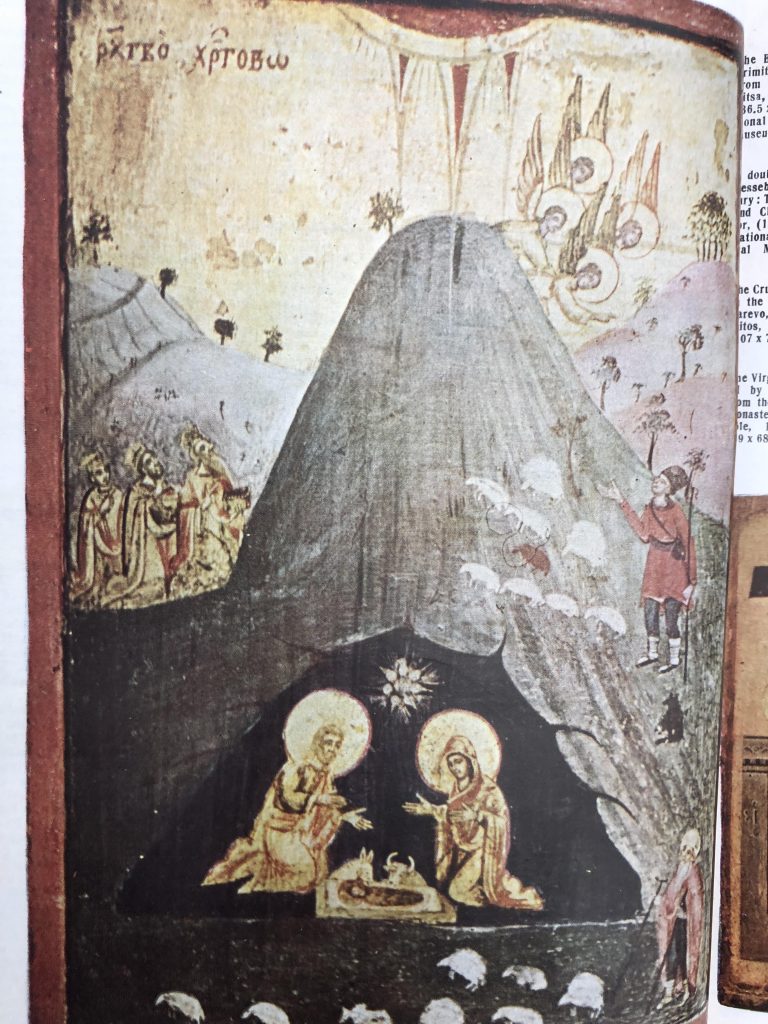

Two of the icons in the collection represent events in the New Testament rather than individual figures. The first is a sixteenth-seventeenth century icon from the Prissovo monastery near Turnovo depicting the Baptism of Christ in the Jordan by St. John the Baptist. The icon is fully descriptive with the Christ figure, the Baptizer, the river, and the witnesses. Unfortunately, the image is truncated and fails to fully show the Descent of the Holy Spirit usually represented as a dove contained within the star ray above the head of the Christ figure. The second icon shows all the elements of the Lucan portrayal of the Nativity: birth within a cave, the Child in a manger with Mary and Joseph, Angels singing on High, the Three Magi bearing gifts, shepherds minding their flocks, and cattle lowing, with the Star from the East shining over it all. An ancient icon clearly telling an even more ancient story.

Fortunately, the governing bodies of Bulgaria did not neglect, or even worse destroy these early medieval icons. Perhaps they recognized their value, possibly through their artistic dimension rather than their spiritual reflection and if so, well and good. Today the icons are among the treasures of Bulgaria which, alongside Orthodox churches and monasteries, are featured as Bulgaria’s major tourist attractions. The small number of icons published in the article revealed the existence of a much larger collection that had nourished the spiritual needs of Bulgarian Christians for centuries and continued to exist within a non-religious form of government to survive until a time when their spiritual dimension can again be relevant and meaningful in a freer civil society.

You might also like:

Free Healthcare with a Price

Yugoslavia in the Third World: Not a New Bloc but Unity of Action in the Interest of Peace

Presenting Prague Spring to the West: Czechoslovak Life and Socialism with a Human Face

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.