April 2015 marks the sesquicentennial of the end of the U.S. Civil War. As we look back on that momentous event in U.S. history, we should take time to reconsider one of the war’s most important figures, Ulysses S. Grant. Most famous as a general, Grant’s life spans an important part of U.S. history. Moreover, Grant’s prose is clear and evocative, proving him to be a great writer,and the author of one of the finest examples of the military memoir.

Grant had resolved not to write his memoirs. However, nearing the end of his life, and with his family’s financial security in doubt, Grant put forth a tremendous effort to tell the story of his military service. The writing does not suffer from Grant’s apparent haste. Instead, the words spill forth from the page and propel the reader through a brief description of his early life, his education at West Point, and his service in the war with Mexico. Grant then embarks on a gripping account of the Civil War from his own perspective.

It is a perspective that differs from many military histories of the war. Grant served in the West during the early years of the conflict. There are no Bull Runs or Antietams here. Instead, Grant gives the reader an inside account of the siege of Vicksburg, a battle of tremendous importance to the Union’s ultimate victory, which is often obscured because it ended on the same day as that more famous battle in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Grant’s account also showcases his genius for war. Like his illustrious predecessor as war-hero-turned-president, George Washington, some military historians deride Grant as a poor tactical general, especially in comparison to his contemporary, Robert E. Lee. While this critique is accurate, insofar as Grant lost many battles, it ignores the far more important object of the general, which is to win the war. On this point, Grant has few equals. And how Grant won the war is most obvious in his description of what he calls the “Grand Campaign” of 1864-1865.

Grant recognized that between 1861 and 1863 the Union had not used its superior strength well, allowing the Confederate armies to survive. To correct this, Grant devised a coordinated series of movements and battles by the Union armies to defeat the Confederacy and end the war. The inclusion of the letters and telegrams that Grant sent to his commanders in the field.makes his description of the campaign and its planning evocative and revealing. These are brilliant: they are concise and precisely convey Grant’s intent for each action.

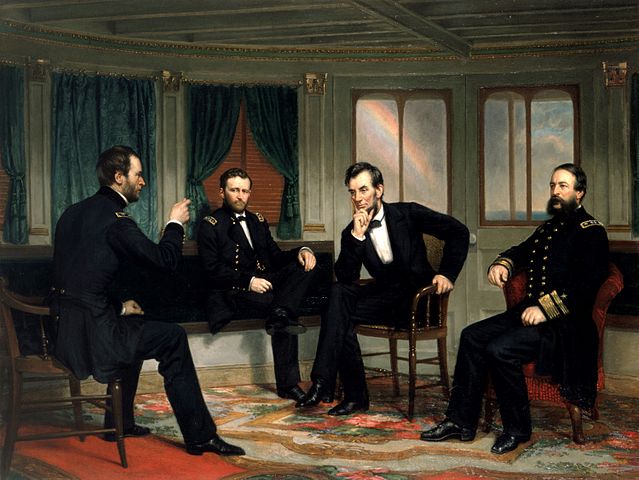

Grant’s memoirs also offer insights into the war beyond its military conduct. Throughout, he presents glimpses of the hardships imposed on the population of the Confederate states by the war that raged on their soil. He is aware of his culpability for this suffering, and, at times, made an effort to alleviate it. He also gives the reader his impressions of other figures, such as Lee, General William T. Sherman, and Abraham Lincoln. These are no doubt colored by the passage of years, but they are also blunt, yet nuanced.

Grant’s discussion of his relationship with Lincoln is fascinating. Much has been written decrying the interference of presidents in military operations, especially with regard to Vietnam. Grant’s memoirs offer a completely different viewpoint. He describes the many instances when he received direct communications from Lincoln about fighting the war, most of which were unsolicited. Rather than condemning these as interference, Grant shows that he understood his subordinate relationship to the president, and thus he vigorously obeyed the president’s orders.

Finally, Grant embodies the complicated feelings that the conflict aroused. He poignantly expresses the conflicting emotions he experienced during the negotiations with Lee for the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia. He relates that, when the two commanders met near Appomattox Courthouse in April 1865, he was unsure of Lee’s feelings, but his own had passed from jubilation about the pending end of the war to sadness and depression. Grant did not want to rejoice over the surrender of his valiant foe, who had battled for his cause, “though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.