This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

1588, Milan. Where via Rispoli ends, you would have found Stefano d’Oriens, owner of a small business selling books and prints. We don’t know much about his operation, except that it sold religious material in formats that were relatively cheap and likely designed to be ephemeral. Given his location at the crook of a road just four minutes from Milan’s Cathedral (the Duomo), Stefano probably did good business—or at least he would have had a shot at doing good business.

That year he published a new edition of a small, eight-page pamphlet that had previously been issued in Bologna almost a decade earlier, in 1579: Avisi notabilissimi intorno al progresso della Religione Catholica [Most notable news concerning the state of the Catholic religion]. The only copy of it known to survive was recently added to the Ransom Center’s already extraordinary collection of English Catholic materials: It describes the martyrdom of four Jesuit priests in 1578, the injustice of their deaths, and consequently their exemplary fortitude. It also underlines the tyranny and illegitimacy of the Elizabethan regime as seen by Catholics and emphasizes the piety of the English Colleges on the Continent, where students were trained for future martyrdom.

In the not-too-distant past, modern scholars would have treated this slight volume as an oddity. They wouldn’t have known what to do with it, and relatively few would have cared to begin with. It would almost exclusively have interested that rare breed of scholar who studied English Catholicism to fight centuries-old confessional battles.

Things have changed.

As I and others have argued, English Catholic history is worth another look for its own sake and because of its significance in European history as a whole. The embeddedness of English Catholics in Europe was not in any way “natural” or foretold; it was the result of active efforts, especially by exiles on the Continent, to become part of a broad intellectual and cultural landscape. To do this, they employed the powerful weapons of paper, pen, and print.

Why would a publisher of quick and saleable leaflets want to publish anything about English martyrs in Italy—and in Italian rather than Latin or English? Simply put, there was likely a market for it.

By 1588, English Catholic exiles had been hard at work lobbying for their cause against the Elizabethan regime and spurring European interest in combating (English) heresy. Perhaps the most important tool to this end was De origine ac progressu ac schismatis Anglicani (On the origin and progress of the English schism), a history of England from the time of Henry VIII to the later sixteenth century written by an influential theologian, Nicholas Sander. Originally published in Latin and adapted and translated into several European vernaculars, the widely influential book insinuated itself in the minds of many and functioned as a dire warning of what Protestantism would bring to even the healthiest Catholic kingdom. England had, after all, been the purest flower of the Church before Henry came along.

The pamphlet might seem like an ant to De origine’s elephant, but it does just as good a job at exemplifying both English Catholic efforts to plead their cause on the Continent and their success. Written before De origine and resuscitated afterward, the Avisi captures, with admirable economy, Sander’s fundamental arguments about Protestant threats and an appeal to other Catholics to take up the English cause.

The Avisi‘s source material, printed and manuscript letters, suggest a world thick with reports on the English Catholic situation. The title works to draw in the Italian reader by announcing itself as broadly Catholic (as opposed to English Catholic), pointing to an effort to highlight the relevance of the English plight to all true believers.

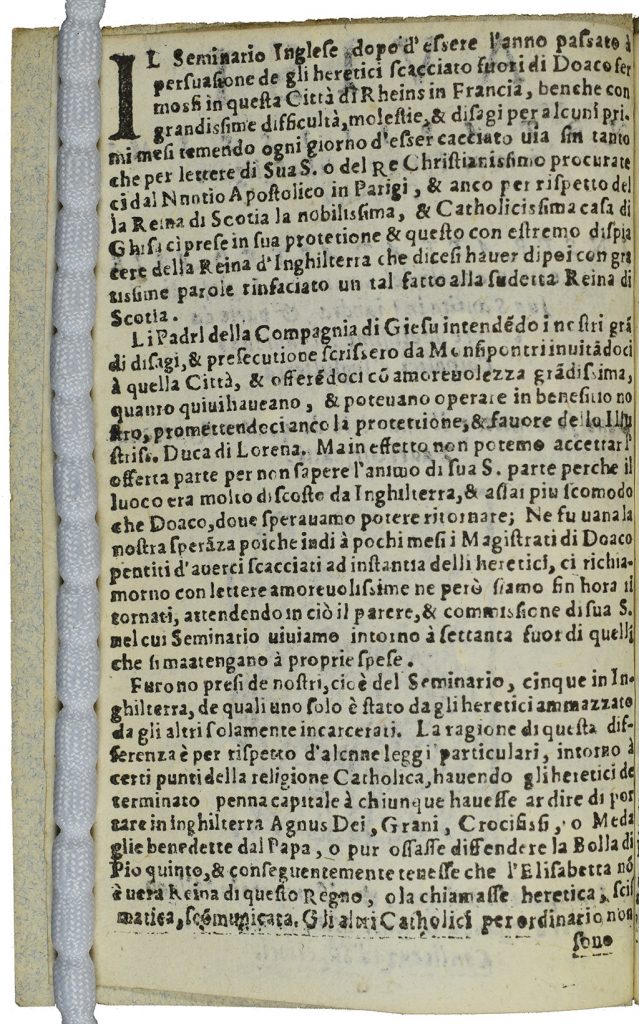

The fact that a pamphlet first published almost a decade earlier could remain in currency so long after the events it recounts had at least something to do with the continued fragility of English Colleges on the Continent. Subject to the whims of kings and popes, the Colleges were often short on cash. The Avisi, in fact, starts with a notice about the 1578 expulsion of a College from Douai to Rheims. Almost certainly as a way to drum up support for it and other English Colleges, the pamphlet tells of martyrs whose role was essential to the salvation of Christendom. Surely, the pamphlet suggests, the institutions that trained Jesuits on the frontlines against Protestant heresy were worth giving a ducket to here and there. Indeed, several of the English Colleges remain operational today.

Importantly, the Avisi is a report specifically on Jesuit matters. It publicizes the death of Jesuit martyrs and the iconography on the title page evokes the Society of Jesus. The printer ingeniously scrounged for a title page image and found one used previously by the publishing house of Giovanni Giacomo da Legnano and his brothers during the first quarter of the sixteenth century. Although the emblem appeared well before the Jesuit order came along, the “IHS” at the center had become linked to it by the late 16th century. The centrality of Jesuits here implicitly fits into intra-Catholic rumblings about the place of the Society of Jesus within English Catholicism, especially in relation to secular Catholic priests, which in turn connected with broader concerns of the Counter-Reformation church.

1588, too, was the year of the famous Armada, the naval expedition by Spanish forces meant to strike a definitive blow against the Elizabethan regime. One of the central justifications for these efforts was the abuse of English Catholics, which was exemplified by the martyrs. The association between the Avisi and the politico-religious moment resonates more when we think that among d’Oriens’s publications that year there was another text—drawn on previous publications in Verona and Piacenza—dealing with the success of Christian forces against the Muslim enemy in 1571 at Lepanto, the result of coordinated efforts among Christian powers that included the Pope and the King of Spain.

Documents like the Avisi can help unleash the imagination. In Rome, it was said that in the 1580s students at the English College would pass out pamphlets about English martyrs to revelers during feast days, a means of self-promotion and promotion of anti-Protestantism. It is easy to imagine that this little volume served precisely that kind of purpose. Though today we turn its pages gently and with some reverence, it’s not hard to imagine the sound of their flutter and crinkle in the hands of Milanese Catholics. In the Ransom Center’s unique Avisi we have a rare survival of the ephemeral that was, in its way, meant to ensure eternity.

Freddy Domínguez is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Arkansas- Fayetteville. He studies early modern European history with a focus on religion and politics. His first book was Radicals in Exile: English Catholic Books during the Reign of Philip II (Penn State Press, 2020). Domínguez is currently working on two edited volumes and a monograph on Luisa de Carvajal, a Spanish missionary in seventeenth-century England. His next book will be Bob Dylan in the Attic: Essays on Music and History (UMass Press).

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.