By Laura Rybicki

This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

Among the many manuscripts from medieval Europe at the Ransom Center are nearly a dozen compact volumes known as books of hours. Though from different places, all were made during the fifteenth century, and each contains a variety of Christian devotional texts. The exact contents vary somewhat from copy to copy, but central in all of them are a group of prayers devoted to the Virgin Mary. They are divided into eight sections to be read at different times, or “hours,” of the day. But while these prayers are what give these books their conventional name, the vivid pictures in many surviving examples are what usually grab the attention of modern audiences. Originally meant by their artists to stoke fervor and imagination, they were surely compelling to medieval devotees, too.

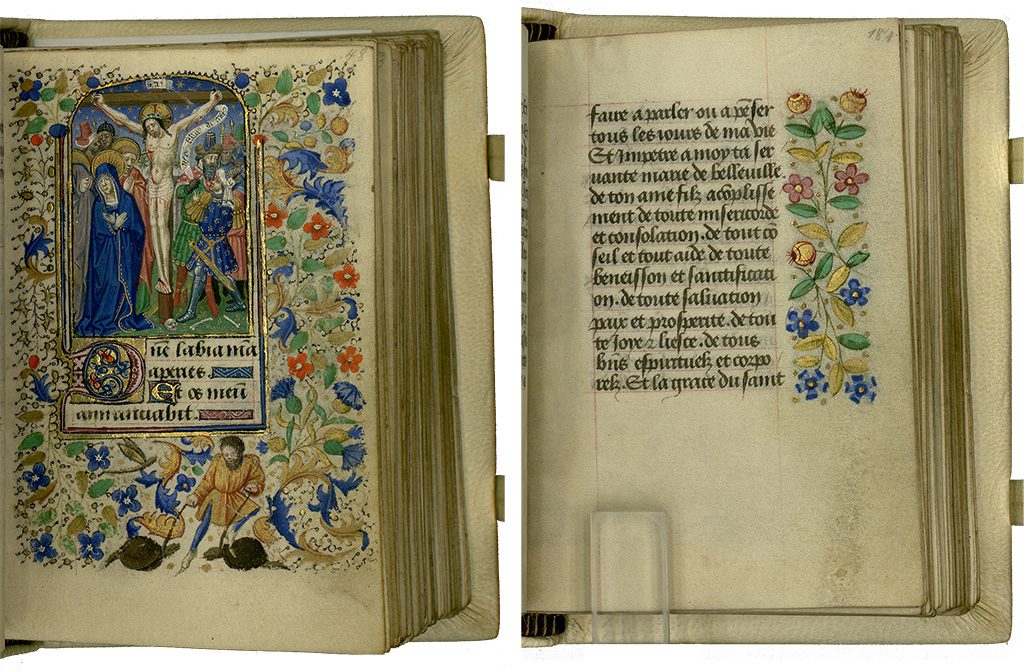

One particularly fine example at the Center is a volume known as the Belleville Hours, crafted in mid-15th-century France for Marie de Belleville, granddaughter to King Charles VI; her name appears in one of the book’s French-language prayers.

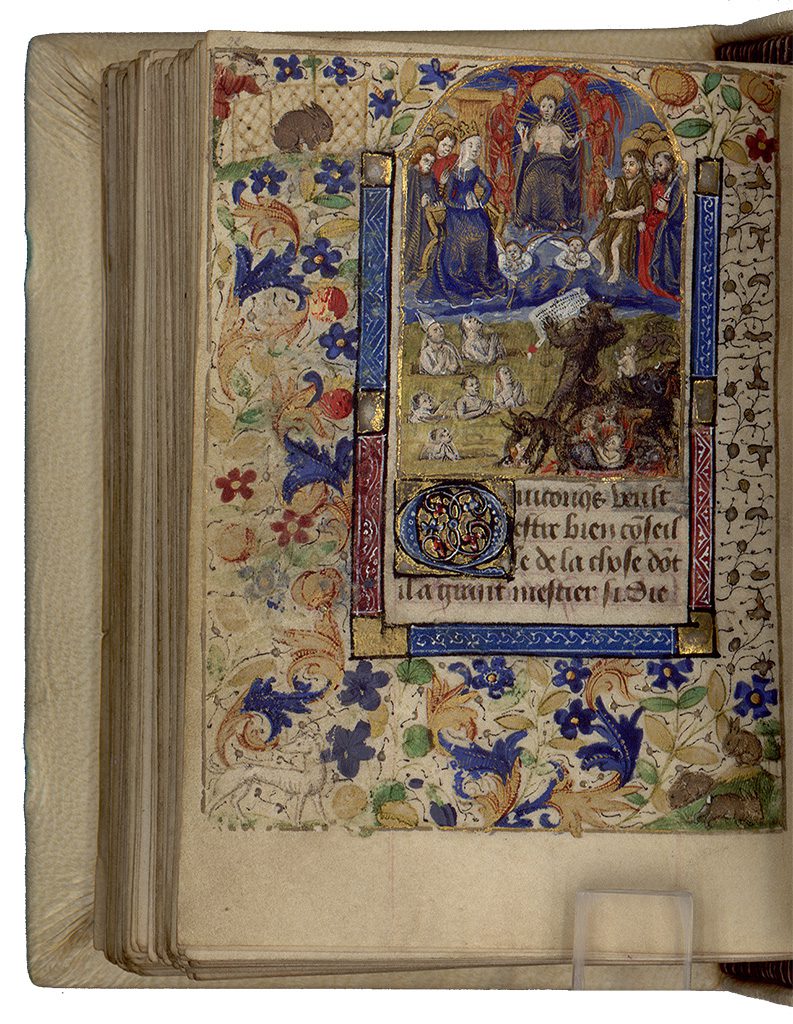

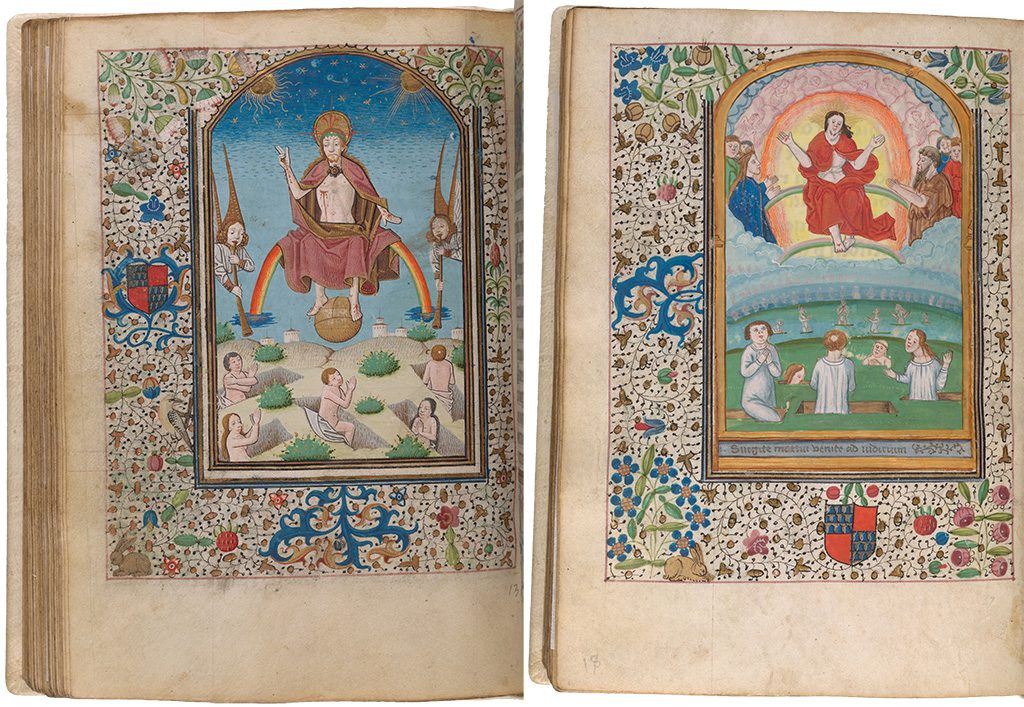

Today, the book’s parchment leaves measure only 12.1cm x 8.3cm (~4.8″ x 3.3″). Even at this size, they manage to include both elegant calligraphy and stunningly detailed miniature paintings and decoration. Among other scenes and figures, one encounters the Four Evangelists, the major events in the story of Jesus, and notable saints.

Surrounding the more than three-dozen miniatures still present—each illuminated with gold—one often finds something typical in books of hours yet seemingly bizarre: lavish plant life punctuated by chimerical and undignified beasts called grotesques or hybrids, and a range of other peculiar figures and scenes. Generally, this marginal content appears to be wholly unrelated to the primary illustrations it surrounds.

For example, in the lower margin of the page showing the Crucifixion, we see a man wrangling two snails on leashes. In the same position a couple of pages later, we see two “wild men” (mythical men covered in hair) rolling around in a field of floral designs, brandishing what appear to be knives; they are under a beautiful and dignified representation of the Holy Trinity. These paintings may have been amusing to their artists and the many reader-viewers who enjoyed them, but there is at least one instance where the imagery in the margins seems to resonate with the miniature it surrounds.

One of the most detailed scenes in the manuscript shows the Last Judgment. In the image, Jesus appears at the top, arms outstretched, surrounded by saints and angels, as the pious followers of Christ await their ascent into heaven. Devils appear in the bottom right, reading out names of damned individuals who are being mercilessly devoured by the flaming maw of hell. This event—grisly, terrifying, hopeful, and triumphant at the same time—is a common subject in medieval books of hours. Images like the one in the Belleville Hours would have reminded readers to remain dedicated to their religious practice so as to not meet the same fate as the damned souls in the illustration.

More puzzling than the main illustration is what we see in the accompanying margins, which depict a medieval hunt. There is a hunter in the upper-left corner, attempting to capture prey that is facing away from him, obliviously enjoying the flowery meadow. Such creatures are somewhat ambiguous, representing either rabbits or hares. Even though they look similar to other medieval drawings of rabbits, the hunting methods on display—hunting with dogs and trapping—may point to them instead being hares. In the bottom-left corner, we see a hunting greyhound, apparently distracted and facing away from three animals playing and snacking on the other side of the page. Hunting scenes are not uncommon in medieval art, as hunting was a popular pastime for the elite, but is there any chance that this one could have something to do with the Last Judgment?

It turns out this pairing shows up elsewhere, too. There are examples of hares or rabbits in the margins of Last Judgment scenes in other books of hours, including manuscripts from other areas of France, such as Brittany and Langres.1 In these examples, they are not being hunted but still stand in the margins of the page, attracting the viewer’s attention. What are these little animals doing there? Could the artists of these and the Ransom Center manuscript have been up to something?

In Medieval Europe, hares were known for their “fecundity and frenzied mating,” and it has been argued that they serve in some books of hours produced for elite women like Marie de Belleville as symbols of fertility, reminders of a woman’s duty to procreate. At the same time, though, they more regularly appear in margins as convenient symbols of licentiousness.2 Because sexuality was an outcome of our fallen humanity, depictions of it in medieval art are often relegated to the margins, apparently unworthy of being a central focus.3 Here, with the hares’ juxtaposition with the Last Judgment, we might suppose that the artist intended the hares to represent (a particularly female?) type of sexual transgression, with the hunter standing in for an angry God set out to punish sinners. In this reading, the vulnerable little hares serve as a warning against earthly desire, which can lead to perdition. The margins thus parallel the main scene on the page by representing the damned facing punishment for their sins, further encouraging reader-viewers like Belleville to make the right decision and choose virtue over more earthly forms of sexuality—lest they be captured by the metaphorical hunter or his dog.

Laura Rybicki holds a B.A. in History from the University of Texas at Austin. She is currently a Gallery Assistant at the Blanton Museum of Art. Her research interests include iconography in Medieval Art, Medieval Decorative Arts, and Early Netherlandish painting. She plans to pursue a Master’s Degree in Art History next year.

1 See, for example, Morgan Library and Museum, Hours of Pierre de Bosredont (Langres, ca. 1465), MS G.55 fol. 139v; Hours of Pierre de Bosredont (Langres, ca. 1465), MS G.55 fol. 77v; Book of Hours (Brittany, ca. 1465), MS M.84 fol. 86r.

2 Madeline H. Caviness, “Patron or Matron? A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed,” Speculum 68.2 (1993), 344. See also, Adelaide Bennett, “A Thirteenth-Century French Book of Hours for Marie,” The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 54 (1996), 26.

3 Michael Camille, Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art (London: Reaktion Books, 2019), 40.